There’s Only One F in Fforest

Terence Evans tells the story of how a South Wales village united to restore a derelict miners’ institute, reviving the spirit that had inspired its construction ninety years ago

It was a classic example of the butterfly effect: the first flap of the wing was an idea for a poem about a humble hairdresser in the small South Wales village of Cefn Fforest. The result so far: hundreds of volunteer hours, tens of thousands of pounds in fundraising and the revival of Cefn Fforest Miners’ Institute.

Shirley the Barber had been cutting hair in Cefn Fforest for almost seventy years, having taken over from her father, Scottie. She had always wanted to be a nurse but her father had no sons, so she took over the family business instead. Over the years she has herself become something of a Cefn Fforest institution, with many residents having had their first ever haircut at Shirley’s. Some of them still have the certificate, along with a sample lock, to prove it.

She was very reasonably priced, which meant many in the village never went anywhere else. I had many a trim there as a child, but stopped going as a teenager when she told me: ‘I don’t do them fancy haircuts here’. Fancy, to Shirley, was anything other than a short back and sides. She was famous for her catchphrase as you got out of the chair: ‘It will look better when it’s washed’. But she was obviously doing something right, to stay in business as long as she did. She had a loyal clientele, including many from outside the village, and whilst you didn’t need to book an appointment, there was always a queue.

As with many hairdressers, the waiting room was a place to exchange gossip and banter and put the world to rights. The walls were lined with photographs from the past; old rugby teams, school classes and charabanc outings.

One regular customer, Dai Potter, had suggested to his daughter, the poet Claire, that she should visit and write a poem about the establishment.

‘I took one look at the place and knew straight away that this deserved more than just a poem,’ says Claire. Wheels were set in motion through contacts in the media and, before you knew it, a short TV documentary The Wall and the Mirror was being broadcast on the BBC.

Throughout the programme, a series of local characters talk about Shirley, the photographs on the wall and the village in general. One of the photographs is an old black and white image of a past committee of Cefn Fforest Miners’ Institute, which prompted a visit to the building.

There’s a scene where former coal miner, Nat Thomas, is walking around inside the old ‘Stute’. ‘It was the focal point of the village,’ Nat tells the camera. ‘Everybody met there.’ The Institute had once been at the heart of the village but had gradually fallen into disrepair, eventually closing in 2012. The film shows Nat looking around the neglected, unoccupied and unloved building. ‘If the old miners could see it now, they would be shocked,’ reflects Nat, appalled.

Miners’ institutes were, as the name suggests, originally built in mining communities to provide social and educational facilities for miners, their families and the community in which they lived. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they sprang up all over the South Wales coalfield, paid for by contributions from the miners’ wages each week.

Whilst it is difficult to tell now, the village of Cefn Fforest was built with the sole purpose of providing accommodation for miners. Situated in the County Borough of Caerphilly, the village sits on the crest of a hill between two valleys, overlooking the Sirhowy to the east and the Rhymney to the west.

As you look around the concrete jungle that stands there now, it is difficult to see where the name Cefn Fforest came from. The name refers to the fact that the hill was once covered in trees and literally translates to ‘wooded ridge’. Maps of Glamorganshire from 1886 show it as Cefn-y-Fforest, with only a few scattered houses in the area, between the larger settlements of Pengam and Blackwood.

Around 1915, five hundred houses were built between the Pengam and Britannia collieries by the Powell Duffryn Coal Company Limited to house workers and their families. Many of the village’s early inhabitants would have worked in those pits, but with the arrival of cars and buses, many men – and it was only men who worked underground – would travel to other pits: Bargoed, Penallta, Oakdale, and further afield.

Former miner Ron Stoate says: ‘I used to fall out of my bed at ten-past six in the morning and be on top of the pit in Britannia, lamp on and everything, by half-past.’

Ron followed family tradition and started working down the pit at the age of sixteen. ‘I didn’t have a car ‘til I was thirty-six. I didn’t need one. Everything I needed was here. It was a two-minute walk to work, or a two-minute walk to the club to socialise.’

The original development at Cefn Fforest was known as Pengam Garden Village and was inspired by Bournville, the model village on the southwest side of Birmingham, founded by the Quaker Cadbury family for employees at the chocolate factory and designed to be a ‘garden’ or ‘model’ village where the sale of alcohol was forbidden. Clearly, not all of the Quaker ideas were taken on. I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you which one was ignored.

The development was one of the largest housing schemes in the country at the time but, according to Wikipedia, today ‘by area, it is the smallest of all of the communities of Wales.’

At the time of construction, it was considered to be one of the cleanest and best laid out villages in the country, providing all essential amenities in one place, including a church, a school and a small shopping centre at the centre of the village.

The village has grown considerably since then and, based on the 2021 census, Cefn Fforest, combined with Pengam, has a population of 7,393, significantly greater than its original 1915 design brief. Housing in the area is a mixture of pre- and post-war, privately owned terraced and semi-detached dwellings, more modern social housing, retirement bungalows and a sheltered housing complex. There’s even a posh bit: Grove Park.

The village has been home to many colourful characters over the years: many of them known to everyone in the village, but not much further. But several have achieved fame far beyond the valleys, including two professional boxing world champions – Nathan Cleverly, who competed from 2005 to 2017, and Robbie Regan whose career spanned 1989 to 1996 – and two professional footballers: Mark Kendal, a goalkeeper who played for Tottenham Hotspur, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Newport County and Swansea City and Wayne Cegielski who played for Cardiff City and also for Tottenham Hotspur.

Patricia Wiltshire is a world-famous palynologist and author who has been involved in the solving of many high profile criminal cases, finding links between suspects and crime scenes through examination of microscopic evidence such as pollen and spores found on clothes.

And last but not least, Dream Alliance was a British thoroughbred racehorse, owed by a Cefn Fforest syndicate. Dream was bred by Janet Vokes and was born on the allotments in Cefn Fforest. The horse proved to be very successful over the years, running 30 races and winning the Welsh Grand National in 2009, landing the syndicate £138,646 in prize money.

Whilst it was the mine owners who provided the original housing in the village, the miners themselves organised to look after each other through mutual aid and solidarity, long before the advent of the welfare state. This was mostly through their trade unions, the Miners’ Federation and, latterly, the National Union of Mineworkers. Hence the prevalence of miners’ institutes across the coalfield.

Miners’ institutes – and working men’s clubs in general – differ from pubs in that pubs are profit-making establishments often owned by a brewery, whilst clubs are owned and run by members, allowing the price of a pint to be kept down. They also have a long, proud tradition of community education and being hotbeds of working-class organising. The Chartists and trade unions grew from working men’s clubs, for instance. However, most clubs these days focus mainly on the social (cheap beer) aspect and that is true of the clubs in Cefn Fforest. Within the village there are currently four working men’s clubs, but no pubs.

As Ron Stoate reflects: ‘Nobody gifted us these buildings, communities built them themselves.’

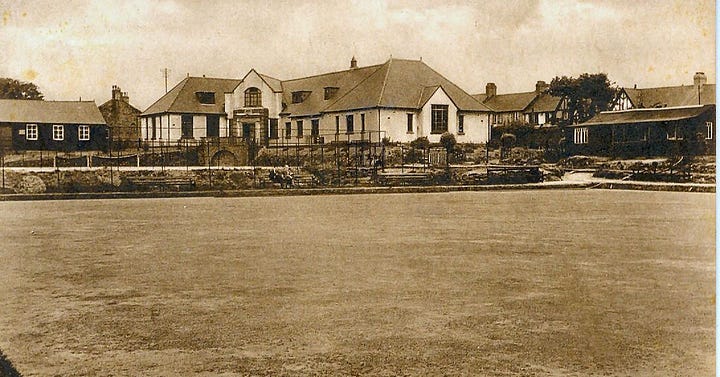

Cefn Fforest Workingmens’ Institute was commissioned in 1927 by the miners of Cefn Fforest and the first foundation stones were laid in 1930. The Institute opened its doors to the public in 1932. The building once housed a library, ballroom and snooker tables, as well as a number of offices and classrooms on the first floor. There was a reading room where local people could pop in and read all of the week’s newspapers.

In the age of the internet this might sound strange but, back then, this was the best way to find out what was going on in the world. As a child I remember browsing through the children’s section in the library, while my mother picked out her Agatha Christies and Alistair McLeans and my dad spent what felt like an eternity reading through all of the week’s papers.

Within the grounds owned by the Institute there was a bowling green, tennis court and cricket pitch. The Stute had a vibrant sporting community, with teams regularly representing the village in football and cricket. My dad and his brother were members of the cricket team and my mother and auntie used to make the ‘teas’ for the post-match socials. Other activities that regularly took place in The Stute include a chess club, social functions, live music and celebrity snooker exhibitions.

With the advent of council-run libraries, the old miners’ libraries became obsolete. Many of the books from over sixty miners’ institutes were collected and archived in the South Wales Miners’ Library in Swansea, which opened in October 1973. Funded by the Social Science Research Council, the project’s aim was to preserve oral, visual and written evidence of coal mining and miners in South Wales at a time when the industry had started to decline and valuable material was in danger of being lost.

In their book, Do Miners Read Dickens?, Hywel Francis and Sian Williams reflect on ‘The Origins and Progress of the South Wales Miners’ Library from 1973 to 2013’ and describe them as ‘The Brains of the Coalfield.’

The mines that provided employment for many of the residents have long since closed. Britannia Colliery is now a country park. On the eastern side of the village there is an ‘Eco Park’ with several walking paths and benches around an area of natural flora and fauna. Some of the park was formerly a coal spoil tip of the type that blotted the landscape through the valleys when coal was king. The tip originally served Pengam Colliery. As a child, my house backed onto the tip and I would regularly get told off by my mother for coming home covered in coal dust after playing for hours on the tip.

To the untrained eye, with the exception of the occasional statue or mural, there is no physical evidence of the industry that gave rise to the community. With the demise of the coal industry funding from the mining communities started to dry up and in the 1980s Cefn Fforest Miners’ Institute was transferred to the ownership of Cefn Fforest RFC. Formed upstairs in Cefn Fforest British Legion (The Dagger), Cefn Fforest RFC rapidly grew from a bunch of mates to a well-respected local team.

Under the stewardship of the rugby club, the building had many vibrant years with the Sunday night disco, affectionately known as The Zoo, attracting people from miles around, although Studio 54 it was not. For a brief period, local champion boxer Robbie Regan used the old function room as a gym, before the building eventually closed to the public around 2012.

There had once been miners’ institutes in every mining community. With the South Wales Valleys built around the coal industry, it meant an institute in every village. There are now only 48 (out of 200) institute buildings left in the whole of Wales.

Oakdale Institute, once the pride of a village on the other side of the Sirhowy Valley, was literally taken down brick by brick and rebuilt in St Fagans Museum. Newbridge Memorial Hall and Institute had to fight tooth and nail to get funding to restore their amazing building, including an incredible art deco cinema. Blackwood Miners’ Institute had a slightly easier time of it, with the council stepping in to refurbish and run the building with a heavy focus on the arts. Many big names from Ocean Colour Scene, the Levellers and Public Service Broadcasting to Manic Street Preachers, Dub War and even a then unheard of band called Coldplay have trodden the boards of the venue.

Cefn Fforest was in danger of becoming another heritage building lost to the community until the screening of The Wall and the Mirror.

In the documentary, Nat walks around the old building, appalled by its condition. You can almost see a tear in his eye. That moment touched the hearts of the village and set in motion a campaign that would result in the village getting together in 2019 to save the building and setting up a registered charity.

Initially, the group was known as ‘Friends of Cefn Fforest Miners’ Institute’ which, with the help of the Coalfields Regeneration Trust, went through the laborious task of registering as a charity, eventually gaining that status in the middle of lockdown in October 2020. The charity was unable to apply for funding until they had formally taken over the lease of the land from the council and set up a bank account, two simple sounding tasks that took an eternity because of lockdown.

Meanwhile, a small band of dedicated volunteers rolled up their sleeves and started going through ninety years of clutter. Old rugby trophies and team photographs were found, along with the committee minutes from around the time of the construction of the building and even the original architect’s drawings, rolled up and stuffed into a breeze block tucked away at the bottom of a cupboard. An old ‘mouse derby’ track was also found, a reminder of less enlightened times.

Since then there has been a two-track approach, seeking grants from major funding organisations and fund raising from events such as Christmas raffles, benefit gigs and sponsored walks. Grant funding was slow in coming initially, with funders making sure their money was not going to be wasted, but several major grants have now been secured, most notably £92,000 from the National Lottery.

Things have been snowballing. The more publicity the charity gets and the more funding they receive, the more the media wants to cover the project and the more funders are willing to donate.

There have been several items on BBC TV News, two BBC podcasts and dozens of newspaper column inches dedicated to the Stute. One good news story was about Chris Williams, son of one of the old institute’s Chairmen. We dug out an old photograph of him as a child sitting on the steps of the building, adding to it sixty years later with a photograph taken of him helping to renew the doors.

Since the pandemic, the price of building work has skyrocketed. Fortunately numerous tradespeople have come into the Stute and done a lot of work for free. There has even been a tutor from a local college coming in, giving young apprentices some valuable practical experience.

The decline of the mining industry means that the village is no longer a dormitory for miners, as there are no mines left for them to work in. With no significant industry or employers in the village, most have to travel outside Cefn Fforest to work. The community has significant challenges with poverty and social deprivation. Private car and home ownership are both below the county borough and Welsh average. 41% of the population have no formal qualifications and 44% are unemployed. Currently, Cefn Fforest has the highest number of people on long-term sickness benefit in the county borough.

The aim is for the institute to provide a facility that will help with the wellbeing of the residents of Cefn Fforest and the surrounding area, ‘providing facilities in the interests of social welfare for recreation and leisure time occupation with the objective of improving the conditions of life for the residents.’ The hope is that it will become a focal point for the community and will enhance social cohesion and community spirit.

The sight of people working on the building has already lifted spirits. Youngsters hanging around the streets with nothing to do are often demonised. Ian Thomas, son of Nat, says: ‘We have had young kids coming in and showing an interest in what is going on. There’s the remnants of an old PA system in the building and they loved coming in and DJing through it. They have even rolled up their sleeves and helped with minor tasks. We asked them what they wanted to see in the building and they were thrilled. No one had ever asked them that before.’

Sadly, Nat is no longer with us and he will not see the building reopened. But his two sons have picked up the baton and are moving forward to keep his dream alive. It will be a few months yet before the doors finally open to the public, but the building is already the talk of the village and people are chomping at the bit to use the facilities. The founding fathers that created this building can rest easy, knowing it is in good hands.

Like many businesses, Shirley had to shut down during lockdown. She decided that it would be an appropriate time to finally hang up her scissors for good. But the photographs that inspired this journey have been donated to the Stute. They will be reframed and rehomed, and placed on a new wall, where they will continue to inspire poets for many years to come.

Terence Evans is a lifelong trade unionist and community activist who writes regularly on music and travel under the name Clint Iguana. Cefn Fforest Miners Welfare hall is registered charity no 1191718. To donate to the project, please visit their website.