Pennorth phonebox, and the last days of analogue

Dylan Moore revisits Pennorth, Powys, the village where he grew up in a time before the internet and smartphones

Little wonder the Tardis in Doctor Who is a police box. Science fiction simply reminds us of the magic in a machine that allows communication with somebody who is physically present somewhere else. In these days of Zoom and Skype, Teams and Meet, we have forgotten just how recently it was that telecommunication changed the world.

Only in the 1880s did our planet become networked with the cables and wires that supercharged globalisation, shrinking the world faster than galleons, steam locomotives and jet engines combined. And the humble red telephone box, now a quaint symbol of a bygone Britain, was once at the cutting edge of communications technology. Yesterday’s innovation is tomorrow’s antique, and just as our homes accumulate obsolete technology that remind us of how history accelerates, so even our smallest rural settlements host these bright red relics, neglected in the overgrowth of hedgerows, disconnected from the networks they once served.

I grew up in Pennorth, a hamlet in the heart of the Bannau Brycheiniog National Park, where you can very nearly count the houses on the fingers of two hands and use your toes to add on the bungalows. Still, we called it The Village. It was simultaneously the middle of nowhere and the centre of our universe. Having arrived a couple of weeks after my third birthday, it was for almost all my youth almost all I knew.

For the years I lived there, I thought of Pennorth only in relation to what it lacked. No shop. No pub, no post office, no public transport. Nothing, or so I thought, of note. Certainly nothing to qualify it as a real village, or to make it known beyond the string of settlements and isolated farms that form a loose necklace of brick and stone around the Africa-shape of Llyn Syfaddan, Wales’ second largest natural lake. But this absence of amenities – this defining lack – grew into an odd boyhood pride in the little that we did have. The tomato-red kiosk near the t-junction at the centre of the village, and its matching postbox secreted within the wall of nearby Cobblers Cottage, became significant focal points for what might in a town or city have been termed ‘civic pride’. If the t-junction was our Trafalgar Square, the phonebox and postbox were Nelson’s Column and the National Gallery. Both landmarks dated to the reign of George V, the letters ‘G.R.’ on the moulding of the postbox and the Tudor crown of the phonebox identifying it as one of the ubiquitous K6 type, commissioned to celebrate the monarch’s Silver Jubilee in 1935.

Pennorth’s other community assets are more recent. I predate the community council noticeboard, which despite a lack of use beyond the odd poster for a harvest festival a few villages away bestowed upon the place the feeling of being, at least, somewhere. And throughout my early childhood, there was nothing to show where Pennorth began and ended. Drivers could pass through in less than a minute and never know they had been. I remember the day the signs arrived, creating borders overnight, casting the Scethrog boys from up the hill as interlopers from elsewhere and my mother’s cleaning jobs in the Big Houses of Llangasty-Talyllyn a short commute.

But it is the phone box that holds the most powerful memories, because that was where we went to communicate with the outside world. Even in a pre-digital age, my family circumstances meant we did not have at home the technology most of my peers thought of as standard. In this respect at least, my childhood was little different to one of fifty years before. In fact, our prefabricated bungalow – sited at the top end of the lane leading down to Ty Gwyn farm and the lake beyond – had been erected during the second world war to house agricultural labourers; intended as temporary, half a century later there it was still, and there we were too. Next door, Mr Jones, a retired dealer in agricultural tools, had a plough in his garden of the type that would have been drawn by horses. On our side of the fence the coal bunker, vegetable patch and Anderson shelter were all reminders of how slow-paced was change around here. I did not find a school visit to St Fagans, the folk museum outside Cardiff, particularly historical. Our only tech came in the form of the record player, the tape recorder – and on the kitchen windowsill, a device my grandparents still referred to as ‘the wireless’.

Television arrived in time for us to watch the end of history, narrated by John Simpson and Kate Adie. The Berlin Wall came down before Christmas and Nelson Mandela was freed in the New Year. I thought the news would always be like this, full of glasnost and perestroika. In summer, we buried my Nanna in sand on Fistral beach in Newquay while New Order set the ‘World in Motion’. Pavarotti sang ‘Nessun Dorma’ and Roger Milla danced around corner flags. Then Grandad died of a heart attack and Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

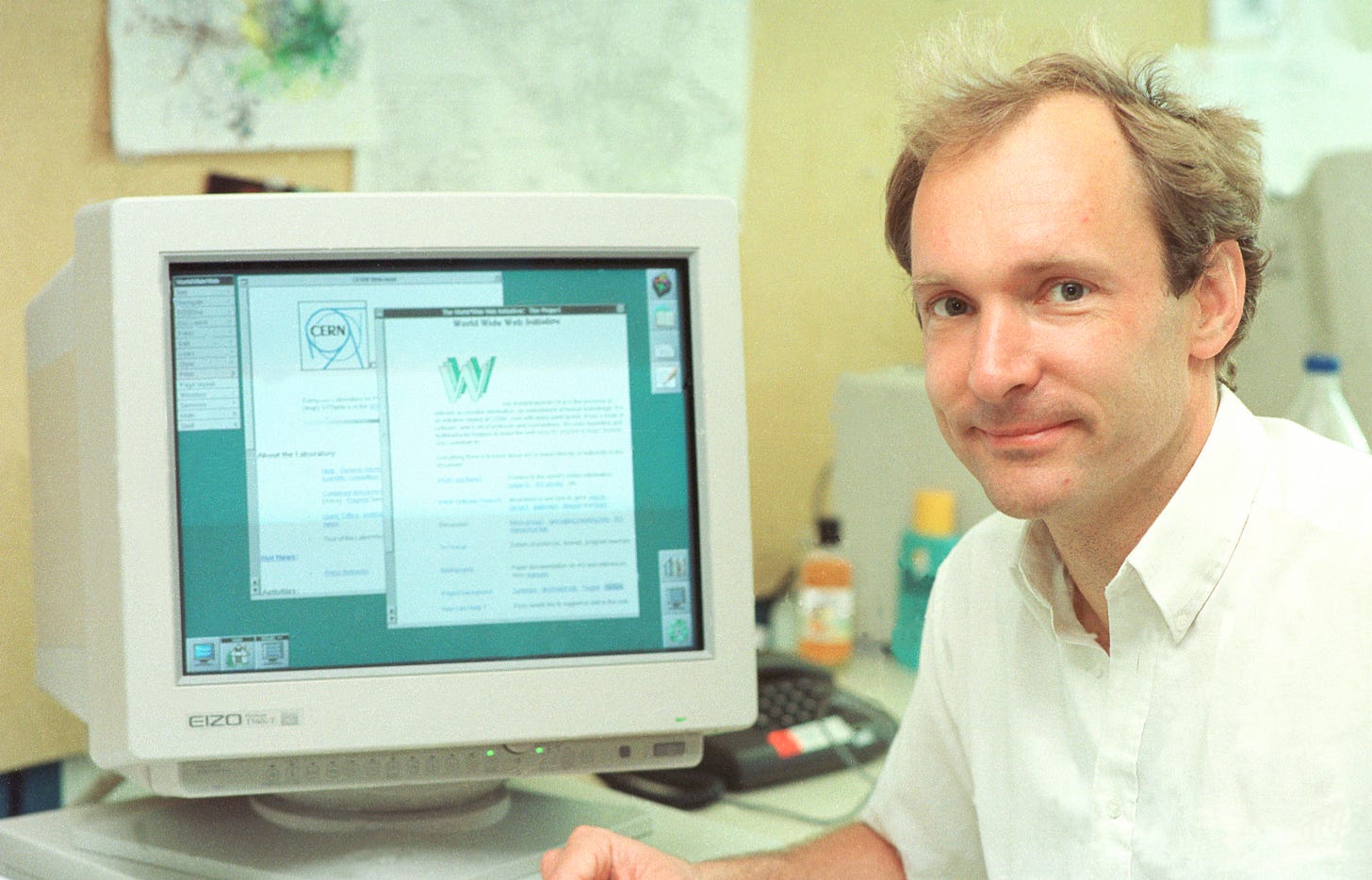

After 1991 things would never be the same again. The Soviet Union collapsed and Yugoslavia began its descent into war. I started high school in September, a month after a ‘universal linked information system’ was released outside of CERN by a computer scientist called Tim Berners-Lee. He called it the World Wide Web, and hardly anybody noticed. Certainly not me. We were not even connected to the telephone network until 1993, the year the internet entered the public domain and just four years before some of my friends began using ‘mobiles’.

I was one of the last generation for whom communication was still linked inextricably to the physical world. Some sociologists call us Xennials, a ‘micro-generation’, squeezed between the preceding Generation X and the millennials who followed. A ‘cusp’ generation. Such labels often seem like forced, broad brushstrokes, incapable of describing the intricate, messy realities of life, but I identify strongly with generalisations about those millions of us born between 1977 and 1983 (coincidentally the release dates of the first and final films in the original Star Wars trilogy). We remember a time before the digital age, but barely. We grew up writing letters in joined-up longhand to penpals in Brittany, Bulgaria and South Dakota. And during the long school holidays, when meeting up in person was restricted to the immediate lakeside villages, limited by where we were allowed on our bikes, I wrote to friends in the Rhondda valley and Hay-on-Wye.

Xennials were the first children to encounter computers in the classroom. I remember flashing green symbols and numerals like signals from a distant galaxy on a Commodore machine, and older kids crowding around a BBC Micro, using the keyboard to enter simple code to make the whole screen turn red, then blue, then green. At comprehensive school, there was a room full of machines we visited once a fortnight. None of the teachers knew how to use them, and any child who did was teased as a ‘nerd’. We dreamed only of Nintendo and Sega. Computers existed, but as portents of an uncertain future rather than part of daily life.

Times were changing, as they always are, but elsewhere – somewhere out beyond the sculptured skyline of the Bannau Brycheiniog which formed the fixed horizon of our finite world. Here we clung to traditions that had already all but died. I remember a Sunday School outing to Porthcawl, an ageing coach hired like a charabanc to take the whole village for a day at the seaside; scenes that would not have seemed out of place in a Dylan Thomas short story. And Sports Day at Treberfydd, the Big House in Llangasty-Talyllyn, where ancient aristocrats still welcomed commoners on high days and holidays. Silver coins – ten, twenty and fifty pence pieces – were handed down to junior race winners by Committee Men in thick framed glasses, all collars and ties behind a table set up in the back of a horsebox. And at Christmas there was carol singing: knocks on doors garlanded with wreaths of ivy and holly and mistletoe, hats and gloves and printed sheets with the words, then mince pies at the Big House where we tipped out the tins and counted donations, peeking into darkened rooms where whole rows of turkeys, stuffed and basted and pricked with herbs, lay in wait for the imminent Big Day. We lived, it seems now, among the last vestiges of an earlier rural way of life, one that relied on a mythology of timelessness to maintain itself.

But history, and the wider world, was right there – quite literally at the end of the garden. Beyond a broken fence, the old railway line used to cut across the open fields. Now its former route was overgrown, the steep banks of its cutting and the canopy of trees that had formed on either side providing shelter for our constant playground, our dens and daydreams, the safety of our wild boyhood adventures.

The coming of the railways is often given as the paradigmatic example of how centuries of rural life gave way to the industrial revolution, and it is easy to understand why. The railways gave us connectivity, and a sense of possibility. Until the Beeching cuts of the 1960s, even here in deepest mid Wales, you could board a train a mile away at Talyllyn Junction and alight anywhere in Britain. What a sense of elsewhere must have been tangible on that platform! Most passengers might have taken short journeys, into Brecon or up to Hay or to Hereford beyond. But railways are deliberately, explicitly a network. Just as the telephone exchange opened up a world of possibilities at the turn of a rotary dial, so the railways transformed completely the nature of places, the sense among residents of living in connected somewheres rather than remote nowheres.

Now I think of that silent innocuous t-junction in the middle of Pennorth, the place where for a decade and a half I waited for school buses to emerge from the autumn mist – at four with my Postman Pat satchel, at seventeen with my Oasis t-shirt and Vote Labour sticker – and realise that the centre of the village was a fulcrum of communication. In the analogue age, here was the ability to commune with family and friends far away, both immediately via the phonebox or within a couple of days via the postbox. Here too, at the very centre of the village was the chance to become involved in the local community through events advertised on the noticeboard, or to commune with the Divine at the Chapel. Only the railway was a ghost.

And if it felt back then that the Chapel was fading, today it has been revived, with services on the second and fourth Sundays every month. The furnishings remain as spartan as the day it was built, but there is Wifi in the vestry. Those few hardy souls who kept the place going in those crucial years when others like it across the whole of Wales were deconsecrated and turned to other purposes, or went completely to rack and ruin, are now buried in its graveyard. The trees along the railway cutting are now so much taller than the bridge that they have had to be cut back. My grandparents died before the internet took over. The boys who surrounded the phonebox with gurning faces as I suffered the heartbreak of being dumped by my first girlfriend are now men in their forties, reduced to the small squares of profile pictures near the bottom of my screen. The phonebox itself has been decommissioned, deactivated and detached. Plants grow in the cracks.

The kiosk is still a time machine. How long ago it seems that I stood here as a child, and how recently. How I am different, and how I am the same. My own four children would barely squeeze in here. Outside, years fall by like rain.

On 31 December 2025, the public switched telephone network will be retired altogether. A network that changed the world deemed too antique to be worth continued use. There is now more information and communication power in each of our pockets than all of the computers Xennials encountered as children combined.

Once our communications infrastructure became iconic through the physical presence of red pillar boxes and telephone kiosks at the centre of our communities, the twentieth century layered onto the mediaeval pattern of fields. Now icons come as rows of logos on homescreens: envelopes representing email; an old-fashioned phone receiver denoting the primary function of the device; pictures of wallets, cameras, books, compasses, lecterns, pens, lightbulbs and parcels. The multifarious functions of a phone that would previously have required half a high street. Soon these symbols will be our only reminders of a fossilised world we have left behind.

What won’t change is our desire to connect. The impulse that brought steam trains hurtling along what used to be tram tracks is the same force that brought mailcoaches careening along the A40 and the miles of cables garlanded from telegraph poles above the hedgerows into the most remote corners of rural Wales. It is also the force that drove me out of the village as a young man seeking the thrill of city life, and the urge that brings me back now, summoning ghosts in the hope of finding meaning in a decommissioned phonebox.

The stale air inside smells the same as it did thirty-five years ago. There is the same concrete floor and the same black metal double shelf where once copies of the Yellow Pages and the latest telephone directory were deposited every year by British Telecom, then the nation’s only ‘provider’. Communications were privatised in 1984, the year after we arrived in Pennorth, part of the neoliberal reconstruction of Britain. South of the Beacons, the Miners Strike raged, but on this side of the mountains we were sheltered. The school concert featured a song that said there would not be snow in Africa that Christmas, but at age five it all got mixed up with Herod and Gabriel and snowflakes made from dot matrix computer paper. There were as few miners in Bethlehem as there were in Pennorth.

The heavy kiosk door swings shut, and I stand in a space designed for a single adult human. In the winter months our family of five would cram inside this box, my little sister lifted to dangle her legs from the shelf while me and brother squashed amid the mass of limbs somewhere nearer ground level, listening to the clunks as five, ten and twenty pence pieces dropped into the bowels of the big metal machine. Down the tinny line came the sound of Liverpudlian laughter and lamentation between smokers’ coughs, as we awaited the regular ritual: the receiver passed down to exchange a few words with Nanna and Grandad before the pips signalled the end of the call.

When we ran out of credit, sometimes there would be a scramble in pockets to find a couple more pieces of silver to buy another minute or so. Sometimes we’d be trusted to slot the money in ourselves. At other times, we simply hurried our goodbyes, and when the phone went dead we stepped out into the quiet country lane, Nanna’s laughter still ringing in our ears.