The blue bridge of the borders

Sara Louise Wheeler writes about the blue bridge over the river Dee at Queensferry, and how it connects her past and present

I’m sitting in the back of the car, lost in a daydream as usual. The car slows down, then stops. Something catches my eye and I look up. I can see the bright blue metal structure through the window; so distinctive, and so familiar. I feel happy. I like this pretty bridge, and I know that, if we are here, then we must be going to Nanny and Grandad’s house, and they’re lots of fun.

This is the earliest memory I have of the blue bridge over the river Dee. It must be the mid-1980s, when I was around five or six years of age, old enough to begin noticing landmarks and relating them to specific destinations, young enough that I didn’t necessarily know where we might be going when we set out on a journey in the car.

The blue bridge is an iconic feature in the borderlands of northeast Wales and northwest England – the country between countries, my home. Its structure and endurance are emblematic of the communities that surround it: shaped by the heavy industries which have since ceased to operate; adapting to the ever-changing landscape and epoch.

In my imagination, the bridge has now also morphed into a strong piece of bright blue thread, sewing a border around the patchwork pieces of my memories, including the new ones I am adding each day. It grounds me, bringing a welcome coherence and pattern to my otherwise confused jumble of incongruous elements and experiences.

Nanny and Grandad were my maternal grandparents – Violet May Elliott Davies (née Harrison) and John Arthur Whomsley Davies. The names on this side of my family always seemed to me rather long and elaborate, yet quite impressive. I was named in the same manner, inheriting the ‘Elliott’, which for some reason was always passed as a middle name to female family members. However, when I married, I dropped Elliott along with the surname Edwards, as it had always caused confusion, at the bank for example. I also wanted a less clunky ‘writer’s name’ and I felt that a three-name moniker was sufficient.

Nanny’s family were originally from Pembroke Dock and Tenby. They had moved to Wrexham because of her father’s job as a Colour Sergeant Major in the army. Nanny’s mother, Gwendoline, had been ‘in service’ prior to marriage. Meanwhile, Grandad’s family were from Rhostyllen and his father worked in the local steel industry. I’m not sure whether Grandad’s mother worked; however, given the family status, and the position of women at the time, it is quite likely she would have been employed in a similar manner to Gwendoline, subsequently spending most of her life as a ‘housewife’.

My mum and her family lived on Ceiriog Road in Queen’s Park, an area of Wrexham now known as Caia Park. From here, Grandad would make the daily trip to work as a welder, riding his bike to Wrexham Central Station, catching the train to Shotton, then cycling to the steelworks on the Dee Estuary, known locally in perpetuity (despite official name-changes) as ‘John Summers’.

Over the coming years, the three eldest of his four children, including my mum, would also make this daily journey, working in various departments of this important local employer. My paternal aunty Brenda also worked there for a while, which is how she met my mum. Family legend has it that my dad was driving aunty Brenda to the works’ party, and they gave my mum a lift; and this is how my parents met.

By the mid-1980s, Nanny and Grandad had moved to a house in Garden City, a ‘planned community’ built to give the steel workers decent housing. My grandparents lived there with their youngest child, my aunty Tracey, who was eighteen years younger than their oldest child, my mum.

Aunty Tracey was cool and bohemian. She wore unusual clothes and had a large fish tank in her bedroom which had a mechanical oyster shell in it. I’d watch transfixed as the oyster shell opened and closed, expelling air bubbles, apparently cleaning the water, somehow. We watched Highway to Heaven and I was enchanted by the feelgood storylines and the handsome Michael Langdon.

Nanny and Grandad’s house was a wondrous place. There were wall hangings with the Balearic Islands embroidered on them and little boxes made of seashells brought back from their holidays. In the lounge there were two large swivel chairs with blue cushioned seats, where Nanny and Grandad liked to sit to watch television together.

They enjoyed throwing big parties in their house for all the extended family. Centre stage at these parties, or so it seemed to me, was a plastic pineapple ice bucket. I was fascinated by this object, which seemed indicative of Nanny and Grandad’s fun attitude towards life. We drank lots of tea from white mugs with small brown and orange flowers painted on them. One of my clearest memories of Grandad was of him drinking tea whilst intensely watching the television, as Margaret Thatcher was giving a speech. Somehow, I knew who she was and something of her significance as a nemesis of this household. I remember him pausing and saying quietly ‘Old boot’ in his distinctive Wrexham accent.

Along the wall of the lounge were some white shelves which served as a dresser, housing a vast collection of Royal family memorabilia crockery. Princess Diana was printed on teacups and plates. This perplexed me as I was aware that this was the British Royal Family, not held in high esteem by others in my social sphere, particularly at my Welsh medium primary school.

A girl in my class brought in a biscuit tin which had a photo of Queen Elizabeth II on it. She explained to us all that her dad had said she couldn’t take such a tin into school just as it was. So, he’d scratched the image, carving the words ‘Twll din i’r cwîn’ (‘Bumhole to the Queen’) on it. Whilst my Nain (on the other side of the family) would never have used language like this, I was aware that her collection of knick-knacks tended to be emblazoned with the Welsh dragon, rather than members of the House of Windsor.

This instance of cognitive dissonance is indicative of my childhood musings. My dad’s family were predominantly coal miners from Rhosllannerchrugog, whilst my mum’s family were steelworkers from Wrexham. Both sides were working class and lived within seven miles of each other in northeast Wales. Yet culturally, they couldn’t have been more different.

My dad didn’t learn English until he went to primary school, where he recalls realising that the words on the board represented sounds that he had heard in the local area, and that this was, in fact, a language. Meanwhile, my mum went to night classes to learn Welsh when I was little. I have a vivid memory of this juxtaposition making itself evident.

We were sitting at the kitchen table, eating our evening meal. My mum was talking about what she had learnt at college and telling my dad that words such as ‘ddaru’ were not, in fact, ‘words’ – her tutor had said so. I recall my dad’s shocked expression as he, as a fluent Welsh speaker, tried to think how to respond.

A few years later, in my first year at Ysgol Morgan Llwyd secondary school, I witnessed a boy from Rhosllannerchrugog being challenged by our Welsh teacher, who was from south Wales; she was saying that ‘ene’ and ‘nene’ were not proper Welsh words, and that she knew his father was a proponent of ‘Rhos dialect’, but that she didn’t like it.

Meanwhile, my Nain (paternal grandmother) Alwen, and her sister Gwladys, would have long conversations where they would say that their own dialectical Welsh was ‘not the proper Welsh’ and that I should concentrate on the Welsh I was learning at school. This was a remarkable thing for them to be saying, considering that they very seldom ever spoke anything other than Welsh!

But Nanny and Grandad were my non-Welsh speaking grandparents, from the side of the family who had large community parties in working-men’s clubs, with buffets of sausage rolls, mushroom vol-au-vents, crisps and lots of mass participatory dancing to tunes like ‘The Birdie Song’ and ‘Agadoo’. Whilst they identified as Welsh, they also seem to have identified as British, including admiring the Monarchy.

Grandad was committed to community life. He was a county councillor, a community councillor, and worked for an MP in the local area. In 1979, he was awarded a British Empire Medal (BEM) ‘for services to the community’, in relation to his work as a convener for the Boilermakers union. This is at odds with my own modern mindset and feelings regarding the British Empire and what such honours represent. However, I completely respect the context and spirit in which my Grandad proudly received his award.

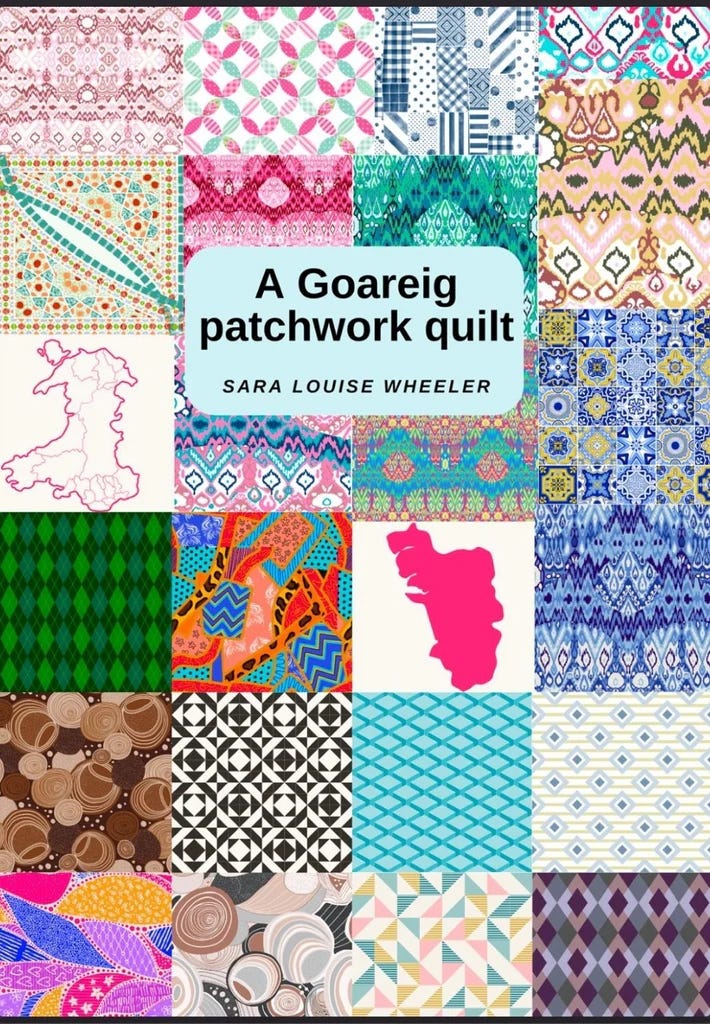

My most recent poetry collection A Goareig Patchwork Quilt contains several poems about my extended family, including Nanny and Grandad. The collection sews together both sides of my family, and incorporates my sister-in-law’s family, who hail originally from Goa, a state in India – hence the portmanteau ‘Goareig’ – Goa + cymREIG (Welsh). Themes in the collection include the family’s roots in, and travel from, Uganda during the expulsion in the 1970s. There are poems about my nieces, as they navigate this multicultural space, and some of my own reflections about becoming ‘Dodo’ (a colloquial Welsh term for aunty).

When I first encountered the Morrissey lyric ‘Irish blood, English heart, this I’m made of / There is no one on Earth I’m afraid of’ I thought at first of Wayne Rooney, famed for his fearless on-pitch presence. Now, engaged in introspection and contextual self-discovery, I find myself pondering what I’m made of.

My first thoughts are ‘coal and steel’, then ‘clay and Ruabon red brick’. I feel rooted in the geology of the borderlands, the associated heavy industries, and the communities shaped by them. Of course, this is only true for a couple of generations of my family, that I can be sure of – and not on Nanny’s side. Also, these industries are now redundant. Nevertheless, my extended family, during my childhood at least, fitted the definition of ‘working class’, and all were based in northeast Wales.

But then my dad passed the 11+ and went to grammar school, then worked in computing, which was lucky because his generation didn’t have the same prospects in the local coal and steel industries. The 1980s were a time of great social and economic change. Meanwhile, our televisions brought us Dallas and Dynasty. My mum became a manager with Avon and lived and dressed very differently to the previous generation of women in our family.

Then, inexplicably – given that the odds were most definitely not in my favour for a plethora of reasons – I not only made it to university but somehow forged a career as an academic. And while this eventually came to an end, my current career as a ‘freelance poet, littérateur and artist’ has me revisiting memories of studying Willy Russell’s Educating Rita (1983) at school. In any case, geographically my soul is firmly rooted in the borderlands of northeast Wales and the ten miles or so beyond.

After an open call from Barddas for poems about the Wales Coast Path, I bought some books and explored the northeasterly sections. In one of the books there was a photo of the blue bridge. A wave of nostalgia enveloped me. I began enthusing about the bridge – its beauty and how embedded it was in my memories. My husband listened, baffled. When I paused for breath, he said: ‘But it’s just down the road from here; you pass it every time you go on the Welsh road’.

I was astonished. I had never noticed it. But it is seven miles from my marital home.

Delighted, I set out one lovely sunny day, to explore the blue bridge of my childhood memories, hoping to be inspired to write a poem for the anthology. It was even more spectacular than I remembered, particularly since the sky that day was a similar colour to the bridge.

Walking across the bridge, I became aware of the unusual textures and shapes within it, partly due to its having been a double leaf rolling bascule bridge. When shipping ceased on the Dee in the 1960s, the lifting mechanism was removed, and the roadway was fixed permanently in place, but the cog wheels remain and add to the character of the bridge. In its structure I also saw echoes of the local coalmine pitheads.

The houses beneath are marked with a sign – ‘Bridge Villas 1897’ – the date of the first bridge to have stood on these banks. In 2005, the blue bridge was awarded Grade II listed building status by Cadw, ensuring that it will continue to endure.

It’s funny how this bridge, which featured so prominently in my childhood, was then absent for several years – indeed long enough to become almost mythical in my memories – yet it is now a part of my landscape once more. It is almost as though it offered a bridge over the intervening years when I felt least like ‘myself’. It is difficult to put into words quite how special this bridge is to me, but I am glad that I grew up in its shadow, and I feel comforted now to know that it is out there still, adding its bright blueness to our lovely borderland landscape.

Sara Louise Wheeler writes the columns O’r gororau in Barddas and Synfyfyrion Sara at Golwg360. She won Disability Arts Cymru’s 2022 Creative Words award (Welsh medium) with Ablaeth Rhemp y Crachach, subsequently published bilingually in her chapbook Trawiad | Seizure (2023). A Goareig Patchwork Quilt (Fahmidan, 2024) is Sara’s latest chapbook; digital copies are available from the Fahmidan website.