The Big Black Wheel on the Mountain

Rhian Elizabeth recounts the story of her grandfather, the Cambrian Colliery disaster, and how she came to understand the importance of 'those bloody miners'

I.M. Hubert Wilcox, 27 July 1925 – 19 July 2002

My mother’s living room, Clydach Vale, Rhondda. It is directly in my line of vision. A commemorative brass and gold plated miner’s lamp that is older than I am, a constant image that repeats on the reel of my childhood memories.

It there next to the fireplace as I am crawling across the carpet in my nappy. It is the tallest skyscraper in the background in the city where my Barbies live. It is not something to be played with. It is not something to be touched. It is something very important.

He was given that when he retired in 1985, my mother tells me.

Now I should warn you that my mother is seventy-seven years old this year and her memory isn’t what it used to be. She regularly calls me by the wrong name, mixing it up with the names of my siblings – so the dates might very well be entirely inaccurate, but I know the story she’s about to tell me is true. Mainly because I’ve heard it around 654 times.

He came to mining late in life, see, because he was originally a baker.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who went down the pits as young boys, it wasn’t until my grandfather was in his early thirties that he took a job at Cambrian Colliery. His mother had been adamant that none of her sons were going to be miners. It was a dangerous profession and, fearful for their safety, she insisted that they instead learn trades. So my grandfather was sent at a young age to learn the art of baking, something that was destined to be his life’s passion until the outbreak of the second world war.

A boy of seventeen who had dreams of crafting cakes and baking loaves of bread, who had never been as far as Cardiff, found himself stranded on a lifeboat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, forced to toss the dead bodies of fellow seamen overboard, awaiting rescue. It was just by chance that he was one of the few who survived. Records I found on ancestry.com showed me that he ended up in Florida and, when he returned to the Rhondda, the curls on his head had been lost to scabies and, no doubt, the trauma of what he witnessed. They never grew back.

After the war, my grandfather picked up where he left off, working as a baker, but the money was poor and with a wife and two children to support, much to the fury of his mother, he took a mining job at Cambrian Colliery in Clydach Vale. Down the shaft into that dark and dangerous place from which she’d tried so desperately to keep him away. She was proven right. He lost two fingers in an accident and then injured his back, but continued nevertheless as poverty was never far away. But perhaps even his mother could not have envisaged, during the worst moments of her worrying, the disaster that was to happen on 17 May 1965.

After a catastrophic explosion, thirty one men – brothers, fathers, uncles, sons – lost their lives. It was only by sheer luck, perhaps the same luck that had been with him on that battered boat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean decades before, that my grandfather wasn’t working a shift that afternoon: he was due to clock in a few hours later.

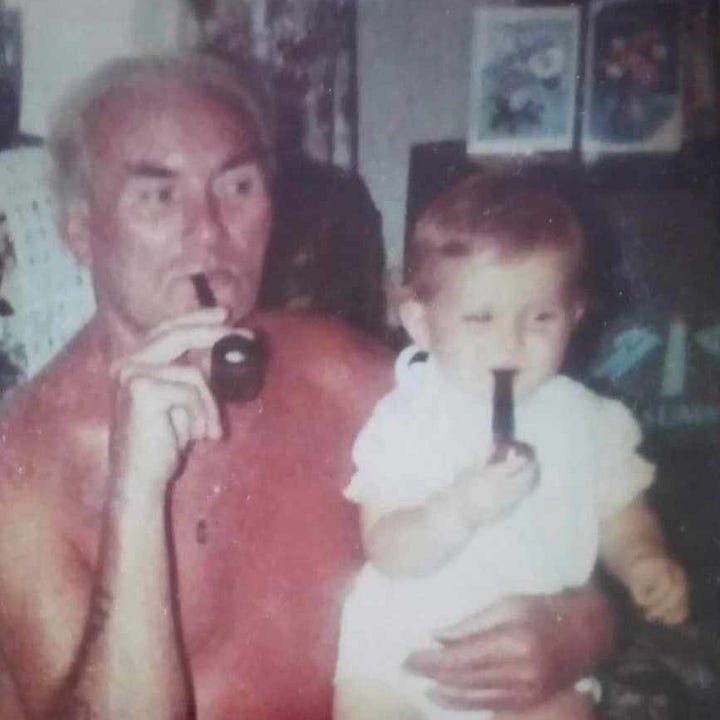

The awful bang could be heard a mile down the road at their terraced house. My grandparents waited anxiously for news. Sitting in his chair that night smoking a pipe, my grandfather found out which of his friends had died by watching the six o’clock news on the telly.

After each name rolled across the screen, he wept.

This a man who never cried, a man who rarely spoke about the horror he’d witnessed during the war, a man who never spoke about his feelings at all. My mother, who had left the Rhondda at aged 16 to join the army and was living in Germany at the time, remembers her officer sending a telegram home on her behalf to see if her father was okay. She was relieved when the reply came, but when she came back home to the valleys only a few months later…

He looked like he had aged thirty years.

I hated how every school trip as a child seemed to involve a bus journey down to the Rhondda Heritage Park where us kids would be forced to don hard hats and shuffle into a lift that sent us plunging down and out into a boring guided tour of a replica mine to learn about miners and budgies and coal and picks and lamps. We would’ve much preferred a trip to Oakwood or Drayton Manor. Why was this dark and dingy life that somehow seemed to define us all something to be proud of, something to be harped on about constantly? Other times our class would let out a collective moan as our teacher announced we would yet again be trekking up the mountain behind our school in Clydach Vale, reluctantly hiking the steep incline with our backpacks and heading towards this massive black metal wheel, yawning as she went on and on, again, about those bloody miners.

I never understood the sacrifices my grandfather and other men made to put food on the table until I was older, how he’d survived the war just to find himself down there in that pit – in another kind of hell. The darkness. The absolute sheer hard work and toil for minimum pay. The chest problems that followed later in life. Or how that big wheel up on the mountain was erected in memory of those men who died in the Cambrian Colliery Disaster of 1965. My grandfather’s name thankfully never ended up on the plaque that sits beneath it, but it’s mad to think of how many school trips I went on up to that big black wheel on the mountain, not knowing the story, munching on juicy jam sandwiches, oblivious to the blood in the ground beneath my feet.

My grandfather continued baking cakes and loaves of bread in the little kitchen of his terraced house for his family and friends right up until he died.

Rhian Elizabeth was born in 1988 in the Rhondda Valley, South Wales. She is a Hay Festival Writer at Work and Writer in Residence at the Coracle International Literary Festival in Tranås, Sweden. She is currently at night school studying to be a counsellor. Her latest book is Girls Etc (Broken Sleep Books).