Teddy Bear

Polly Grace writes about growing up in Wales and the push and pull of home

My dad pointed out where we lived on the map during a BBC weather report. That funny bit middle left that looked like a teddy bear in profile, with outstretched arms – that was Wales. As I gazed at it, Michael Fish peeled rubber rain clouds from his left hand and placed them all over my homeland.

My dad had insisted on moving to New House in 1977, wishing to remove himself from life and people, but mostly people. Our house cowered at the edge of the valley, hidden from view of any cars winding their way up the tiny back road into the hills we inhabited. The farmhouse had one of its four walls leaning outwards, and the attached barn lost its roof in a storm shortly before I was born in 1980. There were no rambling cottage gardens for me to play in, only stacks of brick and piles of sand – the equipment needed for the many and numerous restoration projects – so I ventured further afield for my amusement. The fields that surrounded our house were my playground. I named each corner, my own frontispiece map: Spook Hall was the eerie coppice of trees in the front field, the Stone Table (with apologies to C.S. Lewis) was a large flat outcrop of rocks behind the house and the Pool Tree was an ash with a deep indentation in part of its trunk that filled with water in the autumn.

My little patch of Welsh Teddy Bear expanded briefly when I attended primary school. Then Dad had a run in with the headteacher and I was removed from school. The anxiety I still feel in the pit of my stomach on remembering early encounters with her suggest that his assessment may have been astute. His belief that he could homeschool us was less accurate. This was step two of his masterplan: that he wouldn’t get a job; he’d stay at home and homeschool me and my siblings, and he would finish renovating the house. He removed us from life and people too. But mostly from people. I was to spend the next seven years on that hilltop.

Being homeschooled was great, at least on days when Dad sat silent and dull-eyed in his chair, smoking and drawing black squares on his reporter’s notebook. Realising that his depression had enveloped him, we slipped out, grabbed our bikes and raced around the drovers’ paths on the hill. We explored hedgerows, finding old bottles, blackberries and rusted cart wheels. We ran and shouted and whooped for miles, never seeing another soul and making as much noise as we liked. On days when Dad was bright eyed and whistling, we held wood while he sawed it, mixed cement, sand and water in a wheelbarrow and ferried it to him in buckets, we held the torch while he worked underneath the Land Rover. There was very little homeschooling taking place. This Wales was small, and we were told it was beautiful, but knew nothing else, and the postmen – often the only people we saw from one week’s end to the next – talked of another Wales altogether.

As isolated as the Wales of my primary school years was, it was predictable and familiar and pure. Being thrown from this into the middle of secondary school was brutal and noisy and cruel. Suddenly I was getting up early every day, catching a bus full of strangers, wearing itchy nylon skirts in a shade of maroon I’d never encountered before, and spending my days in musty classrooms of thirty peers. I didn’t know their rules and I didn’t speak their language. I didn’t know how to function in that level of hostility and was completely unable to defend myself. I was unaware of the slang and inferences and would spend my mornings bewildered and humiliated, holding everything in, then I’d go behind the science block at break time and unleash the lump in my throat, hastily wiping away hot tears of fear and confusion before heading into the next lesson.

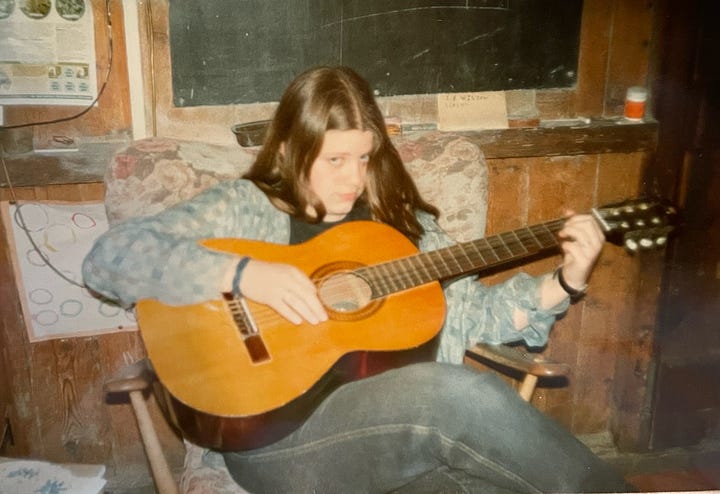

Gradually, I found my way and I found my tribe: initially a group of girls in my form who were all essentially good. We laughed and worked and fought, and with time I realised I was surviving – better than that, I was enjoying it. Later, after a year or so of flute lessons I was asked to join the school orchestra and with that discovered the music block and its crowd of misfits and beautiful people. It was whilst waiting for a lift after a rehearsal I was first asked: “You’re not Welsh are you, Polly?”

Suddenly it was something I had to own up to. Was I Welsh? Well, I’d always lived in Wales… but my dad was English? And, my mum had been taken over the border to Hereford hospital when I was born, so I had Herefordshire on my birth certificate. No, they confirmed, you’re not Welsh. I realised in that moment how many of them had arrived in Wales from elsewhere. From Hull, from Gloucester, from Liverpool, from Salford. And how aggrieved they were about it – that Teddy’s outstretched arms malevolently beckoning them to this land that was so much less cool than its neighbour, with its Eisteddfods and Welsh lady costumes and unpronounceable place names. I needed this non-Welsh group. I needed entrance to it and that was that: I easily renounced any ties to Wales.

As I moved through my teenage years things didn’t get any easier at home. Dad became more and more reclusive, more and more controlling; he’d sit visibly brooding if my mum went out to a work meal. I never joined my peers at parties or pubs; I spent Saturday mornings cleaning the house while mum worked her third job, trying in vain to make ends meet while my dad slept in until late morning.

Around this time we had discovered Craig Fawr. A short walk from our home, it was a small cliff face jutting out of a hill overlooking the river. It was quite magically staged, in that you opened an innocuous-looking gate, wandered into the field and only as you rounded a clump of trees did this incredible view open up in front of you. You could see both sides of the valley from this height and the Wye meandering its way between them towards Erwood, both sides of it carpeted in a patchwork of soft fleecy fields. It was a perfect place to sit in the early evening and watch the sun set. Something about a view like that humbles you, places you, and some of my deepest, most meaningful conversations happened there. Also, incidentally, my first kiss.

The summer in the middle of my A-levels my sister and I went halves on a Sony Walkman which played cassettes. I listened to it whilst ironing in a nearby guest house (my summer job) and as Stevie Wonder played the harmonica solo in ‘For Once In My Life’ a slough of really dreadful suppressed memories bubbled to the surface of my head. I reeled, feeling nauseous, and looking out over the River Wye, I knew I had to get out of Wales, and I had to get as far away as I reasonably could. I had to make sense of everything that’d happened. The impatience, the anger, the shouting, the day Mum came home from work and found us cowering under the trees in Spook Hall, while Dad ranted and raved at us. This poisoned bear had loosened its clutches momentarily, and I had a way out if I had enough courage to take it.

Mum wouldn’t drive on the motorway; we had to be quiet as she came into central Hereford so she could concentrate on the big roundabout, so anything with more than two lanes was well out of the question. I often wonder if I was the only student to arrive on the train with their worldly possessions in bags, carried by their siblings. Years of my dad telling me how appalling cities were and spitting the words ‘council estate’ out like foul saliva, meant I was terrified of what city living would do to me. The basic brick built halls of residence on campus seemed cramped and my room – magnolia walls and beige lino – was soulless and uninspiring. I already felt lost and without a voice in this place. Mum put the duvet cover on the stained bed and my sister helped me put up my Rubber Soul poster. Later my mum was steered away by the shoulders, crying, by my ever practical little brother and sister, and I went back into my beige room, feeling wretched. A tall girl with jam-jar-bottom glasses and a feathery fringe wandered in companionably, eyed the noticeboard and said: “Are they the Beatles? So… which one’s which?”

And so it began. An odd misfit in maroon Doctor Marten boots from Llandod market, I careered through the first term, managing to not quite fit in. “You’re Welsh? You don’t have an accent…” A disappointment again – not Welsh enough. “Wales? My friend’s at Cardiff Uni. Do you know Cardiff?” I didn’t know how to explain that I only knew my little patch. That we’d not had holidays, or day trips, or visits to other parts of Wales. The second that term ended I got on a train, changing at Newport station for my final connection. The drop in air temperature from the south of England made me gasp. I sat on a bench waiting for the Abergavenny train, a surly man sat down a few feet away, appraised me briefly with a flick of his right eye (the left was looking somewhere else entirely) and muttered “Fucking wazzock.” This frosty version of Wales was most definitely giving me the elbow.

My first year at uni was spent hurrying back, calling regularly, worrying about my sister who was having a rough time settling into the high school I’d just left her alone in. Then came year two and I met someone who would change it all. It wasn’t what I’d expected, she wasn’t what I’d expected. There was no effortless slide from friends to lovers, it was messy and disjointed, with fear on both sides. I feel like everything in our initial friendship shifted after a weekend spent together in Wales, where perhaps I made sense, a lonely puzzle piece finally slotted into the right background. The landscape that shaped them. The future was a blur of confusion, not knowing where we might end up or if we’d be accepted. The only thing I was sure of was how I felt. That it was real and powerful, and that however much it scared me, I had to go with it. I walked into my hairdresser one day and asked her to cut all my hair off. Her name was Dee and my recollection is that she resembled Cerys Matthews, but perhaps the desire to be shepherded through this formative experience by the Catatonia front-woman is entirely poetic.

It took me some time to share this relationship with my family. And, to quote Andrew Scott’s character in the movie Pride: “There’s not always a welcome in the hillside.” The best response was from my sister – fourteen at the time – who said it was ‘weird but ok’. The teenage shrug was audible. On every other count there followed telephone conversations with long silences, heart-sink moments when stepping down on to Abergavenny platform, and journeys in a Peugeot 205 thick with unspoken thoughts. For some time, I would visit this hateful version of Wales only when I had to, and slept curled up on the floor in my sister’s room, as if her acceptance was elastic and protected me only as long as I didn’t stray too far from her. This Wales didn’t love me or want me; it mocked me, telling stories of ‘P***s’ now running the local garage (“It’s a sign of the times”) and mimicking Asian doctors at the GP surgery. How had this place ever felt like home?

Years went by and visits happened only a few times a year; things got worse, they got better, they stayed the same. There were a few pockets of comfort and much indifference. After twenty years of emotional abuse, my mum left my dad. He started drinking, and gradually turned Simpsons-yellow as his liver gave up. On one of my final visits, I ran outside the back door and sank to my knees on the gravel rather than watch him dry heaving over the sink. Mum moved into my grandad’s old house in a little village near Builth. The house was so bound up in my memories of them, their wartime-founded 60-a-day cigarette habit that turned the inside of the house a dirty yellow, Grandad eating bread and butter with every meal and Gran’s penchant for pink painted nails. Gradually she made this house her home – a new kitchen, new bathroom; my brother worked some wizardry with partitioning the space upstairs. On rare weekends when all siblings were home, we sat wedged into an impossibly uncomfortable stop-gap sofa and giggled, taking the mick and enjoying each other’s company for the first time in some years. She asked me to house-sit once and in the middle of an incredibly stressful Ofsted-flecked period of my life I found so much peace down by the river. The cool water, pottery sherds and pebbles that had delighted me as a child recalibrated my brain, and despite a partner who was almost imperceptibly slipping away from me, I emerged from the weekend stronger.

Fast forward again and after ten years together and a drawn out, cowardly break up I was suddenly 32 and single. I spent what I termed my ‘Bridget Jones Christmas’ at mum’s cottage in Wales. My grandparents’ house was two doors down from the village pub which made for a very ‘A Child’s Christmas in Wales’ feel. I was viewed as something of a witch as I could work the new fangled iPod they’d installed in the Seven Stars. It was thrust into my hands several times with requests such as: “Hey love, has it got any Stones on it?”. Long after the bell for last orders’ reverberations had faded away and the last stragglers ushered out, I’d be in bed, semi-conscious, as snippets of conversation drifted up through the small square windows. Talk of having to get up for church in the morning and complaints about the dog at the bungalow barking. We didn’t have Organ Morgan but Evan Evans lived a stone’s throw away up Dan-y-Coed Lane.

And just like that I was tucked firmly and squarely back into the arms of the teddy bear – and found it surprisingly snug after all our feuding. The familiarity and comfort of the village after the city was almost overwhelming and after all the years of loving and renouncing and fighting and doubting, I knew it felt like home again.

After ten years of being in a relationship with someone who sat at home knitting, watching dog videos on YouTube and gently nurturing their individual insecurities and paranoia, I was ready to live and to adventure. Not for the first time in my life, I grabbed onto my brother’s shirt-tails and followed him out to the Middle East. He played guitar in a band out there and earned the good tax-free salary they rewarded expat musicians with. I planned to find a British International school and continue to teach primary school children. The weather was glorious of course, the endless gleaming shopping malls were initially fun, but pretty soon it became clear that although company could be found for the night, it would be difficult to find any long term commitment. Where to find my Prince?

He showed up in terrible brown trousers to our first date at a Greek restaurant in Southampton. Blue Island had good reviews but bad wiring, and the waitresses wore pink tabards like school dinner ladies. He had curly hair, a soft Lancastrian accent, a nice smile and he talked and listened in equal measure.

And so the final chapter of my story (so far) ends with a baby. Albert was born in Southampton in 2016 with my husband and my mum at my side. After almost two days of labour he was finally hauled into the world and dropped onto my bosom as I lay in the golden pain-free glow of an epidural. This glorious boy – so anticipated by his grandmothers – was soon whisked to Wales to be shown to his kin. And this is where I suddenly saw the magic of my homeland again through his eyes. The white woolly streamers of sheep’s wool on each barbed wire fence, the yew tree in the churchyard with the trunk that he could climb inside, the corked amber glass bottle in a hedge discarded at some long-forgotten ploughing party. The tiny toes in crisp cold water, chancing among the wavering layers of pebbles in the River Edw. Out and towelled in the sunshine and running bare-bottomed across the meadow, clutching a Welsh cake. This is the teddy bear I loved and that loved me.

Strangely it has taken me until this summer to show my children my childhood home. One afternoon in late August, out of money, out of ideas and fed up with squabbles, I piled them into the car and we climbed into the hills. After a ramble passing a few mini landmarks, we are at the gate, looking down the lane to my New House. “It looks like a haunted house”, says my girl. It doesn’t, of course. But I am disarmed by the comment, and I know for me it is always haunted by the Englishman who so terrified me there.

A few days later and we are less than half a mile from this spot at my aunt’s house celebrating the birthday of a cousin. The day dawned grey but by 3pm the sun is out and the view across the valley is incredible. The cousins bicker and pick at party food, climbing trees, chasing hens and talking to the horse in the next field. Near the end of the afternoon, I line them up on the grass, that stunning panorama behind them, and take photos of them grinning, sticky arms around each other, toddlers held in shot by anonymous arms. And I know that this is where their story will start too. That they will probably fall out with Wales one day, long to be elsewhere, long to leave, go away and love another, lie warm in that embrace for some time. And I wonder if – like me – they’ll return, and fall in love all over again. Because, honestly, right now, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be.

Polly Grace is an occasional author from a little market town in mid-Wales. She is usually found with a laptop on her knees after the children are in bed.