Pursuing Beauty: Tim Lewis and his legacy as a stained glass window artist

Sian Melangell Dafydd remembers the stained glass window from her schooldays that led her to discover the remarkable work of Tim Lewis, who has passed away

It’s the summer of 1969.

See a Mercedes-Benz 220 with the roof down. Bride and groom are standing in the back seats, greeting their family and friends. The bride waves her bouquet and with darting glances looks all about her. As she does so, the white roses in the tall, dark beehive of her hair also seem to wave to the crowds.

The newly married couple are Tim and Janet Lewis of Pontarddulais. From the Mercedes-Benz 220, they hop into a red VW Beetle, equipped with the customary clatter of used cans strung to the back bumper, and off on their honeymoon they go. No hotels, no seaside relaxation, no leisure of any kind.

Tim returns to work and takes his bride with him. They head north, stopping briefly to visit the dramatic waterfall of Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant, before finally reaching Bala on the other side of the Berwyn. Waiting for Tim to return from the interruption of his wedding are two of his students from Swansea College of Art, Stan Williams and Alan Figg.

They had been working together on Tim’s design for a stained-glass window. Yellow posters are up around town, advertising ARTIST AT WORK: an opportunity for the local community to witness the behind-the-scenes of an artist’s process. Tŷ Tan Domen had been their digs until the wedding. They worked there at the former boys’ school turned newspaper printer, sleeping in what had been the headmaster’s office, on the floor. On returning from his wedding, Tim and Janet are housed at Caffi’r Cyfnod, where they were are fed generous homemade meals to fuel the meticulous work.

Flash-forward to 1988.

I was mostly good at school but school was not good for me. Obedient, academic, bullied and increasingly shy, I turned up daily and steadily turned inwards. I was, however, easily wowed by beauty.

I ended up choosing History of Art as a University topic at an institution which I knew little about other than it being ‘good’ (and the prospectus was in my ‘beautiful’ pile on the living room floor). It was also all the way on the east coast of Scotland.

Beauty is usually scarce in a secondary school corridor, but not in mine. My form room was in the old wing of the school, the former girls’ grammar school. In order to walk to the morning gwasanaeth, to go to the toilets, library or reach most classes other than Cymraeg a Ffrangeg, I had to pass Tim Lewis’ stained glass window from 1969.

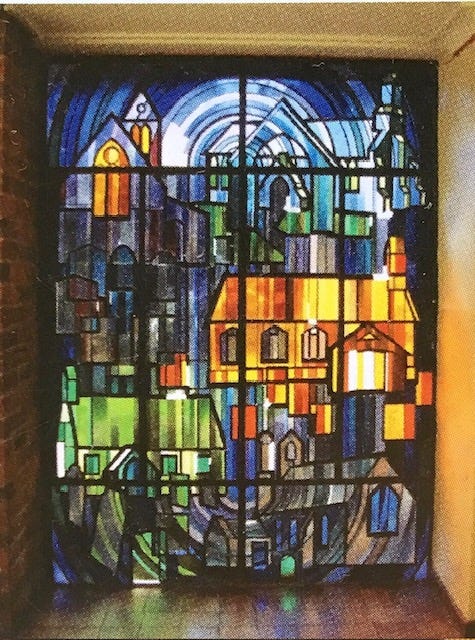

I much later learned that Tim had tried to secure a different location for his work of art, fearing that the south-west position would mean a lot of afternoon sunshine would be on the glass, and therefore its heat. In time, this did become a problem, just as he had predicted, but first, there was a great light hitting his window: it was an almost seven foot by four and a half foot kaleidoscope.

First, I remember the slab of colours blazing into the corridor. That window contained us as we walked to and fro. It held a power in its chosen location because if you entered the building through the main entrance and headed past the library to the headmaster’s office, it could be seen far, far ahead and with every step, grew more magnetic. Right at the end of the corridor, it drew you forward.

[Note: in a writing workshop a long time ago, I swore that I’d never use the word ‘majestic’. That it was somehow so grand that it couldn’t be believed as anything but melodrama. But here I am choosing it.]

Stained glass windows were put in churches to capture the awe and hearts of parishioners. Sunshine multiplied into a myriad colours and refracted onto our skins has an effect of making us feel touched by something beyond education, doctrine or glass. Perhaps we at Ysgol y Berwyn become aware of another connection beyond those long pale-blue walls. Perhaps it being in a school rather than a place of worship caught me off guard. Perhaps daily company with such a vehicle of light is more powerful than weekly on Sundays?

Let me describe this window. At the time, I would have said that it measured just over the height of the headmaster who sometimes stood there in his black cloak between bells, in case a child scraped or bumped into it. Unlike church windows, it wasn’t positioned high above head height but at kicking, kneeing, bumping height. Its size was just taller than the tallest person I knew, and just wider than the span of anyone’s arms. It insisted on being seen. You could face it. Bathe in it. This was Pum Plwy’ Penllyn, showing the churches of five parishes: Llanuwchllyn, Llangywer, Llanycil, Llanfor and Llandderfel. In a watery yet rainbow-like sweep uniting them, was an oval representing Llyn Tegid (Bala Lake).

As it happens, an old (unused by now, thankfully) English name for the biggest natural lake in Wales is ‘Pimble-mere’ or ‘Pemble Mere’ (1813 Cambrian Travellers’ Guide). ‘Mare’ is an Old English word for ‘lake’ in English, coming from Middle French ‘mare’. Think Windermere. ‘Penmelesmere’ was recorded by Gerald of Wales in the Itinerarium Cambriae in the twelfth century and translated in 1804 by Sir Richard Colt as Pymplwy Meer, deriving from Pump Plwyf (Five Parishes). So, this window stood to unite Penllyn in splendid colour. And in many ways, it did. Generations of children from that very circle walked back and forth in front of it; so many cheeks were blushed by its refractions.

I must have been sufficiently moved by the presence of that window in my daily life to have wanted to keep it with me when I left the school, or at least to keep a memory of it with me. I do remember trying to take a good photograph of it. I do remember the challenge: every time I clicked, someone ran past. I remember marking out each panel of colour with black pen on pieces of A4 paper sellotaped together. I then blocked the same geometric shapes with wax onto cotton – a technique called batik. I replicated the colour of each glass panel with silk paint. Once it was dry, I rolled it up at the back of the wardrobe with every intention of quilting or at least framing it. In fact, I moved to Scotland then Italy then France and forgot about the window. But I had appreciated it as a companion. I hadn’t considered how fortunate we were as pupils to have our lives elevated by a work of art of great significance. I hadn’t considered how dull other, normal school corridors were. Neither did I know the name of the artist, nor anything about his career. The window stood for nothing other than itself, until recently. For no particular reason that I can think of, I stopped and wondered: what happened to that window?

All I knew that in recent trips to the library when visiting my family in Bala, all the walls had moved. There was no space for a window in the new configuration of school walls. So, in its absence, I looked for that old batik painting of mine and I began researching. Someone had a vague memory that the artist was called Tim. I started there.

Tim Lewis studied at the Royal College of Art in London under Laurence Lee, one of the masters of the craft in Britain, and is the former head of the Stained Glass department at Swansea College of Art. I scrawled through examples of his work on Stained Glass in Wales and recognised his style immediately. Our Pum Plwy Penllyn wasn’t on the first page, nor the second, nor the third. It was missing in more ways than one then. I learned that he was one of the most important artists in the medium working in Wales in the second half of the twentieth century. This window of his in Bala was his first public commission and the earliest example of his tradition-forming, technique-forming life as an artist. Yet there was no mention of it.

One among many of his famous works is a window to remember the crew of a Mumbles lifeboat who all died in a storm at sea in 1947. Where the rhythmic shapes of saints might be expected, Tim Lewis shows man after man in a yellow raincoat, the sea in their hands at the north isle of Eglwys yr Holl Saint, Ystumllwynarth, Abertawe (All Saints Church, Oystermouth, Swansea). It is the same window which appeared on the cover of The British Art Journal’s summer issue, 2015, in which the editor declares that Martin Crampin’s book Stained Glass from Welsh Churches ‘may well be the most beautiful book ever on stained glass’.

Listening to Tim speaking on a Welsh television programme about the window, he explains how he wanted to grasp the feeling of being at sea and went out with the lifeboat himself and took part in an exercise with them. It was winter and misty. The boat swooped into the waves from the ‘house’ (he gestures this with a dramatic hand). ‘Mi ges i ryw fath o…’ he says – I had some sort of – and then he stalls and his voice quivers before saying ‘o brofiad’ – of an experience.

He wanted a window that was special to the Mumbles, not Jesus walking on the waves and quietening the sea but something unique to the tragedy. At the bottom of the window, he showed Mumbles itself. His interest in architectural features of a place is here, as they were in Pum Plwy Penllyn. The castle, lighthouse, the place where these men had lived – small houses – one particular street with interesting lines, huddled against the mountain. He shows black and white photographs of these places that were taken as field work. Most of the colour in the window comes from the blues and greens. The sea, he says, and right in the centre of the window, the tragedy. The men stand upright and strong. He specifically wanted to show them this way. Dynion cryf, dynion cadarn.

Here is Tim Lewis the social observer and then Tim Lewis the artist. He speaks of his pencil next, and gestures not as if swooshing a boat into splashing waters but a delicate pen, slowly carving a line in air. He draws shapes as though for lead or glass by nature now, he says. It comes over time. He thinks in this method. In his gesture, I see how he imagines the matter of his material and is somehow in union with it.

[Dear reader: I am listening to Tim’s explanation of the details in this window, the real life world of the Mumbles and its tragedy, his experience in the grasp of the sea, and his wish to show the men in strength when my phone beeps and Tim’s daughter informs me that tonight, Tim Lewis passed away. He is both alive in his work and there is also this news. May this appreciation of his line and light of beauty reach you. May you visit some of his windows, listed on Stained Glass in Wales’ website.]

Let me introduce you to some. First, the Round Window in Stanwell School, Penarth. They are luckier than Ysgol y Berwyn and the window still survives. Tim’s granddaughter studied here and was able to live a little with her grandfather’s representation of the phases of the moon imprinted in the school’s daytime sky. Secondly, consider visiting In Adoration of our Senses, also at the Eglwys yr Holl Saint, Ystumllwynarth and Christian Symbols at Eglwys yr Holl Sant/Church of All Saints, Rhiwbina, Cardiff: windows to linger under. I also want to mention the windows in the Chapel of Remembrance, Coychurch Crematorium, Bridgend, made by staff, students and distinguished visiting artists of the Stained Glass Department of Swansea College of Art. The Four Seasons windows there by former student Roger Hayman are a set of four tall window with vigorous abstract designs – on a good day, you will be saturated by colour, just as I was as a school pupil in Ysgol y Berwyn. The cloister windows at the crematorium include a long line of memorial windows designed by Tim Lewis, Alan Figg, John Edwards, Mark Angus, Yanos Boujioucos, Amber Hiscott, David Pearl, Lydia Marouf and Janet Hardy (1970s work), while the opposite windows are by four masters of a post-war renaissance in Germany – Ludwig Schaffrath, Joachim Klos, Johannes Schreiter and Jochem Poesgen (1979-82). There are also windows by Christian Ryan and Alexander Beleschenko (1983). May all the seasons of life be remembered when we are grieving. May all who grieve witness beauty like this and be held by it.

Most of Tim Lewis’ work is to be seen in the Swansea area, south Wales at the furthest, but nobody knows why he was matched with Bala for the Artist at Work project. One other window commissioned for The Open University in Milton Keynes, showing a blazing sun with its rays intertwining outwards, is also lost (at the time of writing). Does care diminish with distance?

Glue certainly weakens with time.

Tim Lewis was right about his reservations regarding the location chosen for Pum Plwy Penllyn at Ysgol y Berwyn. It was so often in the line of light at its strongest. Colour and line in this large, immersive work were at their best in the glare, but the glue was not. So, this is where we reach an interesting point in Tim Lewis’ developing technique at that time. He is known for an approach to stained-glass windows which was new in the 1960s. Those familiar with textile techniques will know of appliqué work: when pieces of fabric are sewn or stuck onto a larger piece to form a picture or pattern. This method was used in ancient Egypt to adorn garments and household items. The very same principle, applied to glass, is what Tim Lewis saw as a creative solution that created new, dynamic possibilities in bending light. No lead was used in his windows. Light in weight and light in lustre, Tim Lewis’ style and technique was given its first public commission away from home and in Penllyn.

This appliqué technique is so often discussed in a context that leaves Wales out. This article is a small step to rectify that. Tim Lewis was not alone in pursuing a new approach to capturing glass without the weight of lead. The bonding of coloured glass to plate glass with an adhesive like this (usually epoxy resin) was used in other locations in the 1960s. When the parish church of Blackburn was enlarged and embellished to serve as the Anglican cathedral, a huge lantern-spire was created. This octagonal lantern was designed by Laurence King with the aim of flooding the alter below with light from eight richly-coloured windows. The commission for the large octagonal glazing scheme was given to John Hayward who created what was possibly the largest group of windows in the UK carried out in appliqué glass. His method, described by Norman H. Tennent resembles that which Janet Lewis has mentioned in conversation – of washing each separate, small slither of glass before application. Tennent writes about keeping the pieces under cover before assembly (no dust, presumably). During the laying-up and use of the epoxy resin adhesive, the temperature was maintained at about 21°C. The epoxy resin and hardener were measured out using hypodermic syringes with a third syringe used to apply the resin mixture to the glass. He writes about the dark lines made with a ‘cement-silversand mixture to which a polyester resin was added’ and this chimes with Stan Williams memories of a product named ‘slate’ being used in this context (appropriate for Wales – I got a little excited when at first we thought real slate was in it but no). In the case of the Blackburn Cathedral, the first piece of glass became detached in September 1970.

Sheffield Cathedral and St John the Evangelist Church, Eastbourne had appliqué windows by Keith New. They, like Blackburn Cathedral, suffered the same fate: the glass-to-glass bond began to fail within a few years. Now, none of these windows remain. Conservation was deemed unrealistic. On the other hand, the sculptor E. Bainbridge Copnall was commissioned to design and create an outdoor screen commemorating the life of Sir Winston Churchill for a shopping precinct in Dudley near the city of Birmingham in the mid 1960s. in this case, conservation proved unsatisfactory and a few pannels of the original appliqué work, Churchill Memorial Screen remain in storage with no current plans for redisplay. Glass, like light itself, in some cases has proven to be ephemeral.

Let me return to the case of the Blackburn octagonal lantern-spire. A stained-glass conservation consultant proposed using a more durable adhesive. John Hayward, the artist himself, considered reversing the glass and providing an exterior protection. However, it was also Hayward’s view that, ‘in the event that a decision is made to replace the existing glass, the appliqué panels should be destroyed rather than stored’ based on the important principle for Hayward ‘which has something to do with not clinging to the wreckage once the ship has gone down’.

We are in the process of considering the restoration of Pum Plwy Penllyn. Based on this, with a heavy heart, some might agree with Hayward’s comment in the late 1980s that we should let broken glass lie. Indeed the price will seem prohibitive, as is the fact that there is no longer space for the window where it used to be, and as a relic of sorts by now, we might consider Tim Lewis’ original caution as well as the headmaster’s fear of passing feet. So where else might the window go? With no home, it’s difficult to even begin a restoration project at any price. However, it is no longer the 1980s. Luckily, our window was not destroyed. It remains, albeit in pieces, in bubble wrap and safe. Opening corners of the wrapping and peeking at the combination of colour and cracks, the current headmistress of Ysgol Godre’r Berwyn (the school’s new name) and I were both stunned. It is so very beautiful. It is so very damaged. Whenever it was taken out of its original home in the school corridor, it wasn’t done so with the same awe as we felt faced by its beauty. Brute force was used. It’s hard to understand how human hands might have done this. But we have not lost the window. We are reassured that the adhesive now used for appliqué glass work is a world apart from that which the 1960s artists used. So much of the early appliqué work of that time is now lost. Pum Plwy Penllyn doesn’t have to be among them. For now, light does not travel through its coloured glass but I for one would like to again be saturated in how Tim Lewis saw our community. This time, glue will not grow old.

1969. Tim and Janet Lewis have arrived at Caffi’r Cyfnod. Cake and cups on Formica tables. Friends take up their work again. How much work is still to be done, how the public are responding to witnessing the process. Janet is recruited to wash the meticulously cut morsels of glass, yet to be applied to the sheet glass in Tim’s design.

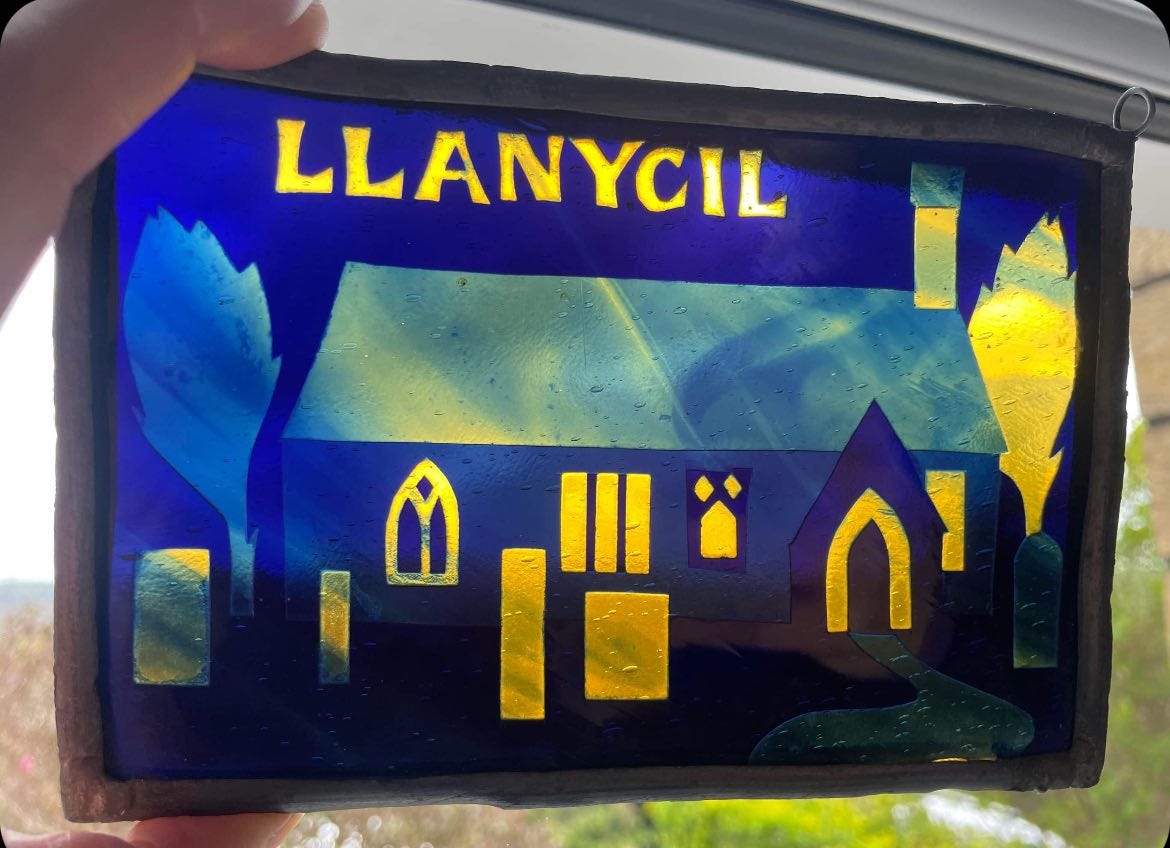

The making of Pum Plwy’ Penllyn meant driving around the plwyfi (parishes) and photographing the churches there, much as Tim Lewis had done in Mumbles for the Lifeboat Window. I imagining him choosing his angles and lines just like the lifeboat men’s homes. He and his students made small panels of each church, practicing their facades, turning their stone faces into bright colours: a fiery orange for Llanycil, greens of mosses for Llanfor. One such panel remains with Tim’s family: an early appliqué practice piece of Llanycil in blue and yellow, bubbles visible in the coloured glass as the light shines through it. There will be other practice panels out there in the community somewhere. They were given away to local people as thankyous and parting gifts, so I am told. Still, nobody locally has any memory of them. Should anyone read this article and think: I’ve seen something a bit like that at the back of a drawer somewhere, please, do get in touch. We would like to see these small panels exhibited together as a family, or at least know if they survived.

The wedding video ends with window building. The large, seven-foot-tall structure has many of the coloured church bricks in place, but they are held together with gaps. Llyn Tegid is missing so the churches float in the air. Tim Lewis steps to the glass so that he can position one sunshine orange little panel on Llandderfel church. He then steps out of the camera shot and we see no more.

An exhibition, Pum Plwy Penllyn, showing the work of Tim Lewis will be at Capel Plase, Stryd y Plase, Y Bala, September 12th - October 3rd 2025.

Darn hyfryd. A lovely piece - his windows are things of awe. The lifeboat window is staggering in its scale and storytelling and sits across from his window of the last supper, looking down on the hands as they ate.