Investing in bonds: the fall of the Llanishen tax offices

Martha O'Brien explores generations of association with Llanishen through the lens of an unlikely building

I grew up in the suburbs with the sound of the city. Train on the hour, every hour, its movement on the bridge over the road like a giant breathing in, breathing out. Sounds of the drill from the garage in front of our house would echo in the early morning. When we were kids, we’d stand on the dining room table at the back of the house to look over the garden at the local reservoir, watch birds as small as fruit flies floating on the water. Dad would bat back the nettles at the bottom of the garden with a huge wooden slat to make a path for us to wade through, emerging slightly scratched into the playing field where we’d run and pick blackberries until the sun went down. That was before the housing developers built the new estate, and our playground, our view of the reservoir, was blocked by rows of three-storey houses. Our village is one of the oldest in Cardiff, sat beneath Caerphilly mountain with leafy greenery and fresh rivers. But my village as I know it, as I have known it, is this: train, garage, tower block. Tarmac, pub, leisure centre. Grey, wet, grey, and wet. I love it here.

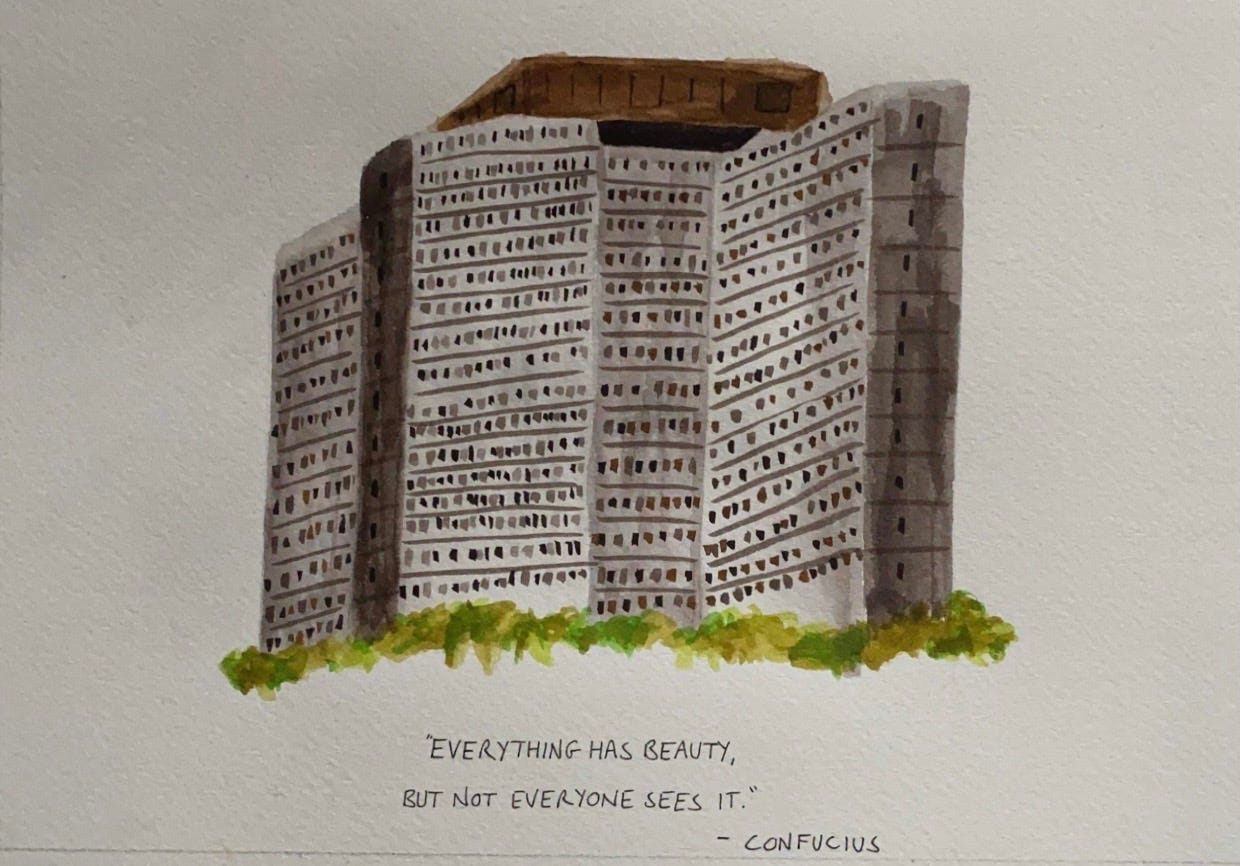

My Nana sleeps still in the room my Mum was born in. My Mum lives round the corner. My sister lives next to the doctor’s surgery. For my brother’s seventeenth birthday, she presented him with a hand-painted picture of the Llanishen Tax Offices. ‘Everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it’, she had written at the bottom. My brother has joked for years that the HMRC offices in Llanishen are his favourite buildings in the world. Forget the Taj Mahal, the Eiffel Tower, Pisa and the Pyramids, Llanishen tops Dom’s list as the site of the greatest architectural achievement in human history. The joke was always funny for two reasons; the first and most obvious was that the buildings are regularly referred to by most Cardiff residents as an eyesore, ugly grey Brutalist tower blocks that have been unoccupied for eight years. The second reason was that, in some way, we all completely agreed with him.

My Nannie and Grampy moved to Llanishen in 1967. They had met in Sheffield on a bus on the way to a dance, after moving to the UK from Ireland. My Grampy grew up in the south in Tuam, Galway, and my Nannie lived in rural Strabane, outside of Derry. Their immigration to the UK was simple: like millions of Irish people of their generation, they were forced to leave through poverty. When my Nannie left Strabane in 1955, she didn’t return until my Mum was a little girl over a decade later. They moved to Cardiff and were married in 1958, living first in St Fagans before moving to Llanishen and settling in the house where my Nannie still lives. My Grampy was a builder and in 1968 he worked on the foundations of what became the Llanishen Tax Office buildings. My Mum was born the same year.

My grandparents had no choice but to leave their childhood villages, and in some ways it feels like a kind of poetic justice that my Mum, my siblings and I have become so attached to our own. We all grew up here; my Mum went to the same primary school we did, we’ve caught the same train and buses into the city. Llanishen, by the time I was a kid there, wasn’t the quaint suburb that it might’ve been when Oliver Cromwell stayed at the Church Inn in the village. Farmland has long been replaced by housing developments, and the village looks not unlike most suburbs in the UK. When walking in nearby Cefn Onn Park – an oasis of green amidst the houses and shops – we’d climb halfway up to the Graig, where you can see right across the city, over to the Bay. At that distance, it might be difficult to discern our village from the grey squares around it – that is, if it weren’t for the two, noticeably bigger grey squares sticking out of the skyline.

There had been talk of the old tax office buildings being demolished for years before the demolition began a few weeks ago. They were once the site of major employment in and around Llanishen. My auntie and my uncles have worked in the tax offices over the years; when my uncles were boys, they used to get their hair cut there too, in the oddly-situated barber’s. In recent years though, they are neglected, unused, and the land they occupy might offer space for a new school, or (as is becoming a theme here) more housing developments. Unlike the Iron Bridge chimneys in Shropshire – similarly noted for their ugliness and familiarity – which had a dramatic controlled explosion bring them down, the tax offices in Llanishen have been brought down bit by bit, taken apart slowly, exposed and gutted. I’ve heard that in the process of their slow death, rats have run wild in the gardens of the houses nearby, like some biblical plague has been unleashed by the demolition of these iconic buildings. Or maybe that’s just what happens when you leave a building to rot before deciding it needs to die.

Perhaps it’s strange or downright stupid to feel any sentimentality towards two tower blocks that symbolise the bureaucratic arm of late capitalism. But we’ve all got those markers; we’ve all got something that looks like home. I read Thomas Hardy, who evokes so much in the history of Dorset through space, who evokes his home authentically in what now feels like a form of historical record. I read James Rebanks, who so praises the beauty of the Lake District and laments its change, feeling a rootedness in the place he was born, lives and works. Hardy and Rebanks’s work, though over a century apart, share a connection to nature, to the preservation of that nature, expressing fears over what happens when we slowly tear away at the earth that we should look after. I can’t align the change in my own environment with that kind of protection or preservation.

There is a similar uncanniness that comes out of the feeling of these buildings being removed, though. The farms my grandparents grew up on had been in their families for generations; the hills, mountains and sea around them had remained unchanged, their faith unquestioned and practised over centuries. The closest I’ve got to a kind of environmental stability in where I’m from, of a waymarker or a feeling of recognising home, has been two tower blocks that are only as old as my mother.

I walked to the village last week. I smelled wild garlic blooming by the river – out too early this year. Even the fields, even the weather is not constant anymore. I don’t lament for the ‘good old days’, and I don’t believe in hiraeth. But there’s something strange in returning home, finding somebody has changed the furniture, repainted the walls while you’ve been gone. It wasn’t that you especially liked the old armchair in the corner – but it was yours. Though my Nannie and Grampy were forced away from familiar environments, it feels now that those familiar environments are all, everywhere, being ripped away from us.

When I arrive in Llanishen, one building is still standing. The other looks sad and naked, not even a quarter of the size that it was, with building materials waving sadly in the breeze like white flags and seagulls nesting temporarily in the hollowed out offices. Maybe they will build a school. Maybe the place will be put to good use. Maybe it will be the landmark that my niece and nephew, still too small to remember anything yet, will call home.

We build things up, we knock them down. I’ve seen demolitions in passing, on the street as builders gut houses, on the television as buildings fail to be saved (though, I must note, there was no ‘SAVE OUR TAX OFFICE’ protest). The councils of today erase the mistakes of the people who came before them – excessive acceleration and dramatic, public backward pedaling. I realise that the buildings coming down, the deep feeling they evoke within me, the one that drives me to drone on about it, is a part of something bigger. I don’t want to leave the generation after ours with tower blocks and grey tarmac, but it would be nice to leave them with something. It would be nice to make decisions that they don’t feel they need to undo. It would be nice to see organisations come together to invest in something meaningful, something beautiful, something made to last.

Martha O’Brien is a writer, researcher and editor from Cardiff. She is co-founder and co-editor of nawr magazine.