Inside London's Welsh chapels: 'Singing the Lord's song in a strange land'

An encounter with an unexpected seam of Welsh culture in London spurs Rhys Underdown to explore the city's history of Welsh chapels

Capel y Trinity is perched snug in the middle of Glanmor Road, a steep street in Swansea lined with tall trees. I don’t know what kind of trees they are, but in my memory they are always green and dripping with rain. The chapel stands among rows of large semi-detached houses but eclipses them with its own size. It is separated from them by tall iron railings and a gate, and straddled by two hefty stone pillars.

As far as my reasons for being here, I am not entirely sure. All I know is that it was not until a few weeks after moving to London, and walking into Capel y Boro (a Welsh chapel in the heart of London) for a male voice choir rehearsal, that I suddenly remembered about Capel y Trinity. Only then did I give any serious thought to the fact that there, between the age of about seven and nine, I had attended Ysgol Sul, or Sunday school, more or less every Sunday, along with my younger brother and a couple of school friends. I’m not sure whether it was the interior of Capel y Boro that brought these memories to the fore: the smell of the wood from the pews and that heavy musk that makes your head go dizzy for a few seconds; or the sound, and the peculiar way in which voices reverberate with a certain broad, eerie timbre; or the ever-present silence, even when there is noise. Perhaps it was simply the shock of finding such a seemingly familiar environment where I had least expected it, in the heart of London. But for whatever reason, Capel y Boro stirred memories of this forgotten but formative period attending Ysgol Sul in Capel y Trinity. And so, I resolved to pay it a visit the next time I was in Swansea.

This took two years to get around to doing, however, as these things do. On a cold morning last December, on the way back from a haircut in the Uplands with an afternoon gaping wide ahead of me, I am struck with a desire to see the chapel again. And so here I am stood, outside Capel y Trinity, Glanmor Road, Swansea. A thick chain lies upon its gates. I am having a good look at it for the first time in almost twenty years, or perhaps ever. The chapel itself is not that old, as far as chapels go, having been built in 1954, but it looks somehow older than its seventy years, and not in the usual way that chapels and old buildings do. The engraving of its name, carved into the stone arch above a thickset wooden door, is quite faded, and the year of its founding barely readable. While it was originally established as a Methodist chapel, a modern plastic sign now clearly reads ‘Eglwys Bresbyteraidd Cymru’ (Welsh Presbyterian Church) and lists its opening and closing times. The path leading to the chapel door is slightly overgrown with weeds and leaning long grass. A brown stain rises up against the outside of its pale tobacco-cream walls, almost like the damp earth itself is creeping upwards, sucking it down. Apart from a nativity scene atop a plinth on one of the gate’s stone pillars, which could have been placed any time between the last year or five, it looks seldom visited.

The Sunday school is attached to the right of the chapel, and is somewhat older and smaller than it. A sign on the roof above the door reads ‘Glan-Môr – Cangen Ysgol Trinity M/C Abertawe’ [Glan-Môr, Swansea Trinity School Branch], and then beneath it the year of its establishment. It was run by the mam of my mam’s best friend from school, whom we called Anti Glenys, and who would read to us patiently from the Welsh Bible. We sat obediently through these readings, out of deference to dear Anti Glenys, who tried her best to keep us engaged with questions and narrations of the Bible’s better-known hits – but this was on the one condition that we could draw while she did so. And, being the age we were, our primary interests during these years were soldiers, guns, and fighting in general, and so these were the core subjects of our doodles. We produced ream upon ream of drawings depicting gruesome battlefield scenes, and I’m sure the sweet irony of our violent sketching being accompanied by messages of kindness, forgiveness and cariad Duw was not lost on Anti Glenys, though she showed little signs of impatience with us. Then, every few months, we’d get up in front of the congregation and sing Welsh songs or perform on the piano, which we called a gymanfa ganu, or a singing recital.

Since I could not get inside today, all I could do was imagine its interior, and I realised that I could walk through the entire building from memory. We would enter the Sunday school through a small side door, walk past ten or so rows of plastic chairs which were never used, to the back of the room, where there was a long table at which we’d sit. Anti Glenys would stand at the head of this table and read to us while we doodled. There was a piano or an organ against the opposite wall, and straight ahead, opposite the double doors, was a small kitchenette, where we were not allowed, and a bathroom next door to this. Then, to the left of the table was another heavy wooden door, beyond which was a passage that led to the chapel.

This is hazier in my memory, as we went inside only for our gymanfa ganu, and I suspect that some of my memory of its interior is informed by watching home videos of us playing the piano and singing. I remember where the piano stood — just behind a pillar nearest the pulpit, to the right hand side. I remember the smell of this room (though all churches have that hollow, old-wood smell), and something particular about the light (though all memories are coloured by that strange iridescent brightness). I remember talking with old ladies who said they were in school with my nana, or who knew my mam when she was a girl (I remember finding these claims utterly unbelievable). But I also remember the excitement of being allowed up into the pulpit to recite poetry or sing songs, and of the thrill of having one’s voice amplified by the microphone as if by magic. It strikes me that, as a musician and performer now, perhaps this early enjoyment of using a microphone might have stayed with me somehow, and note the fact that it is once again music that has drawn me back to a similar interior in Capel y Boro.

Upon my return to London and spurned on, perhaps, by my failure to gain access to Capel y Trinity, I was inspired to find out more about the Welsh chapel that I knew about in London, Capel y Boro, and discovered, to my surprise, that there was a network of other surviving Welsh places of worship of various denominations dotted around the city. I made a list of them and went about visiting as many as I could, though this proved more difficult in practice than I had anticipated; they are so disparately spread out around London and its outskirts that, considering the slightly limited windows in which churches are typically open, it would take months to see them all. So, perhaps favourably for the purposes of this piece, my search was limited to three.

Why I was doing this or what I could really hope to glean from doing it, I’m not entirely sure. But I figured that by just going to them, and hopefully gaining entry to them, I could discover more about them and the people who use and engage with them than I could from merely reading up about them online. I wanted to see in what ways, if any, they were self-consciously ‘Welsh’, and how they communicated this. I was motivated, I think, by a disbelief that these places and any aspects of their ‘Welshness’ could survive in a city that, on its surface, is so all-consuming.

The venture began with disappointment. My first port of call was Jewin Church, near the Barbican, and not far from where I am currently living in east London. It was one of the only Welsh churches in London that was advertising a service on the first Sunday after New Year’s Day, 2025. I also read that it was one of the first specifically ‘Welsh’ places of worship in London, built in 1774 and motivated by the increased need to accommodate the growing influx of Welsh migrants into London; a series of sites and chapels were founded on various nearby streets, until Jewin Church’s permanent location on Fann Street was settled upon. And so my partner Evie and I wound our way around the deadened Sunday streets of Farringdon and Barbican, without a soul in sight. It was drizzling, and January’s icy grip only deadened the silence further.

Even though the church itself is eclipsed by the skyscrapers and towering flat blocks which populate this part of the city, Jewin Church remains an impressive structure. Damaged significantly by bombing in 1940, it was rebuilt in 1960 and now boasts a sturdy modernist frontage of dark brick, with deep wooden doors marking the entrance, its spire scaled by narrow slivering windows of steel-coloured glass. Around the flanks of the church are smaller, squatter windows that could be opened, and one of them was. But that was the only evidence of any activity inside the church, because, although we’d arrived in time for the bilingual service as advertised, there was nobody around, and the doors were securely locked. I knocked, circled the whole perimeter, tried other doors, but to no avail. Either the website was incorrect, or simply nobody had showed up.

So we were forced to gather whatever information we could from outside of the church. A sign on the wall reads ‘Eglwys Bresbyteraidd Cymru’ (Presbyterian Church of Wales), ‘Sefydlwyd [Established] 1774’ below which is information regarding ‘Amser yr Oedfaon [Times of Services]’ and ‘Croeso Cynnes I Bawb [A Warm Welcome to Everyone]’, and some other contact details. Below this is an engraved stone slab, now quite difficult to read, but which commemorates the Mayor of London’s reopening of the church in 1960. There was no English on either sign, apart from the translation of the church’s name. This was surreal to me, being in such a central part of London. Around one corner there was another sign, unrelated to the church, marking Fann Street as the area in which Huguenot fan makers worked and met to ‘adopt their new constitution’ in 1710, serving as another suggestion that this building and the surrounding area were perhaps more indicative of cultural movements which were beyond them, of which they were merely a seam of a richer tapestry – that perhaps the Welsh aspects of this place were subsumed by history and London’s rich culture. I noted that the church shows up on Google Maps as ‘Capeli Cymraeg Llundain’ (London Welsh Chapels), portraying it more as an emblem of the wider network of London’s Welsh chapels, rather than an active church in and of itself. It made it all the more noteworthy, however, that such a building had survived. Without being able to get inside, I conceded defeat and left somewhat dejected.

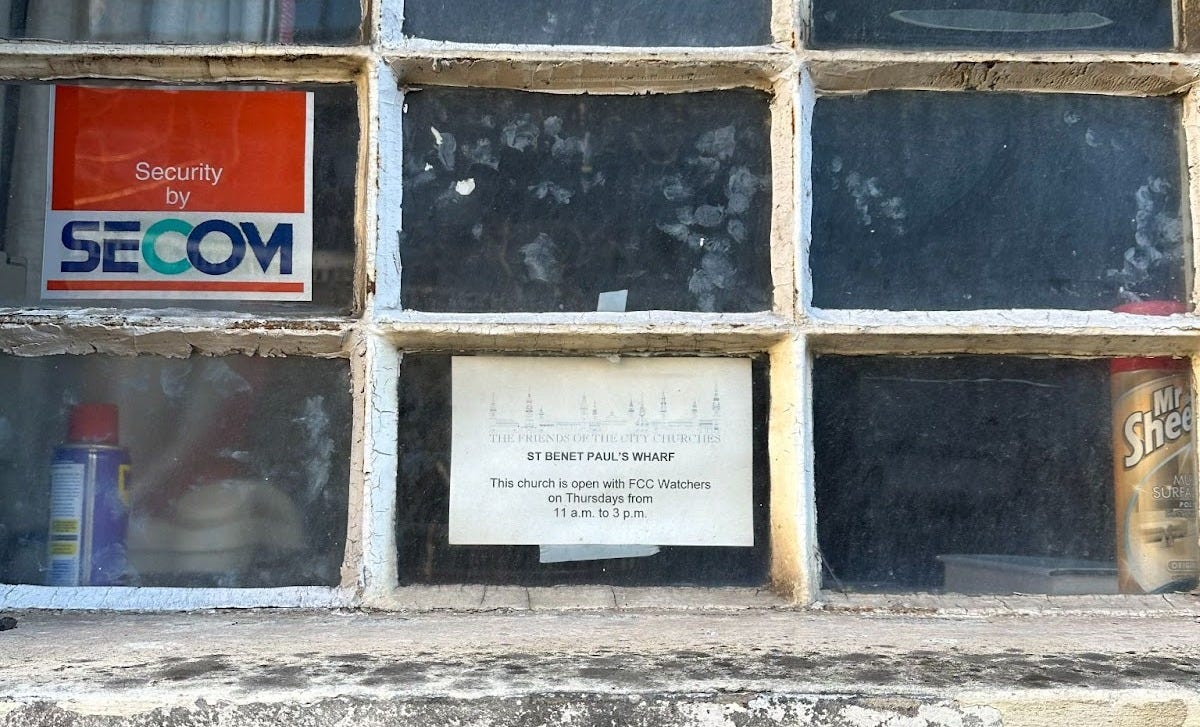

I was resolved to continue with the project, however. The next spot on my list was St Benet’s, Blackfriars. It was a ten minute walk from my place of work on Fleet Street, so I decided to head there one day during a lunch break on Thursday 9 January, the following week. I had read online that, on this day, an organisation called ‘Friends of the Church’ volunteered and would be available to show me around the church between the hours of 11am and 3pm. At around 1pm, I headed over. The cold of London had deepened, but on this day the sky was a glorious blue. I walked along the Thames which was dazzling as it whipped beneath Blackfriars Bridge and London Bridge. I dodged runners and walkers on the river path and listened to Bob Dylan’s Modern Times, and felt a keenness to get inside a church this time. I scaled some steps away from the river and emerged on the bend of a quiet street where there seemed to be some construction underway. I immediately saw the tower of St Benet’s, with St Paul’s watching indifferently in the background, hardly even aware of this humble and relatively little church existing a few hundred metres or so away, although both churches were built at similar times, designed by the same person.

A church dedicated to St Benet has been on this site since 1111 AD, though it only became a self-proclaimed ‘Welsh’ one in the late nineteenth century, and its history is as extraordinary as any old church in the heart of London has any reason to be. Lady Jane Grey and Anne Boleyn were given their last rites here in the sixteenth century, before immediately heading for their respective executions (likely via the Thames). Shakespeare (who once lived nearby) refers to it in Twelfth Night (Feste reminds the Duke Orsino that ‘The triplex, sir, is a good tripping measure; or the bells of Saint Bennet, sir, may put you in mind – one, two, three’). The architect Inigo Jones was buried here in 1652, and, after being destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, it was rebuilt by Christopher Wren. It is allegedly the only one of the churches of the City of London that has remained unchanged from Wren’s designs, and one of only four City of London churches that were unscathed following air raids by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz. However, the other three were affected either by IRA bombs or renovations, so it likely is the only church in this area that has essentially remained the same since its rebirth in the seventeenth century.

That is, of course, apart from one significant change which came in 1879. In the 1870s, the church was considered unnecessary, given the City of London’s declining population, and was scheduled for demolition. But Welsh Anglicans sent a petition to Queen Victoria herself asking for permission to use the building for Welsh-language services. In 1879 she granted this permission, and such services have been held there ever since.

Before I learned all of this, however, I was, yet again, definitely locked out. The ‘Friends of the Church’ were nowhere to be seen, and despite knocking loudly on the door, and attracting the attention of several homeless people who were residing in tents under a bridge across the path, I conceded that, as with Jewin Church, I had consulted an out of date website, or had got it wrong. Either that or, more sadly, there was nobody here looking after this church. Its website’s information page had, after all, been written in 2015. I saw a doorbell by the firmly locked entrance and rang it as a last resort. I heard no bell ringing inside, waited a couple of minutes, and started to walk back towards the Thames, again deflated.

But as I was rounding the corner to join the street, I heard the door open and a tentative ‘hello?!’ calling after me. Turning around, I saw an old white-haired man leaning outside of the doorway. I scampered back and asked him whether I could go inside and take a look, explaining that I had some interest in London’s Welsh churches. The man’s name was Hywel, and he spoke with a London accent (he explained he had lived here for forty years but was from Llandeilo originally). He granted me access and led me in, locking the door behind him.

It was immediately clear that this church wears its Welshness very much on its sleeve. Welsh dragons on wooden crests line the walls, and enormous Welsh flags hang gracefully down from the gallery above as you walk in through bulked up wooden doors. Hywel allows me ten minutes in which to wander around the church as I see fit, as he has a call to make, and so I stand mostly still in the silence of the space.

I wasn’t entirely sure what I should do next, or what I was looking for. But there was no secret that this church seemed to be hiding. I suppose I was surprised by the overtness of its display of Welshness, that a church in so central a part of London was manifesting its Welshness so obviously. These were my own presumptions, of course. Perhaps I had actually been hoping that, Indiana Jones like, I would be forced to explore the church crypts for older evidence of half-forgotten Welsh parishioners, or uncover hidden manuscripts buried in the church walls.

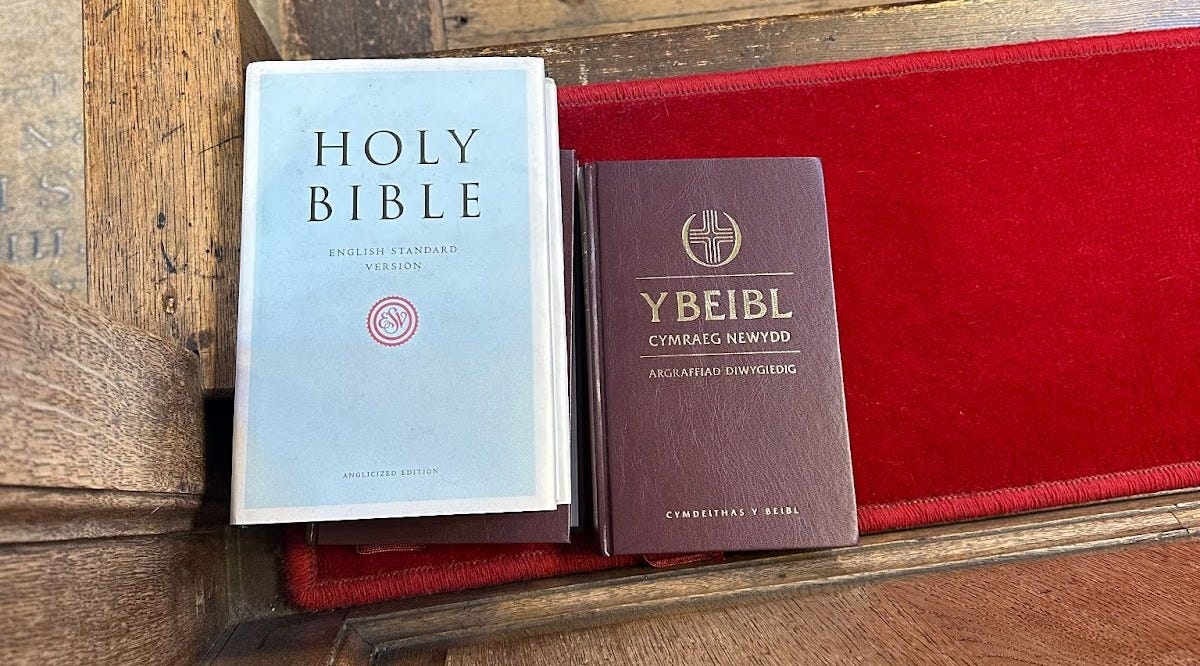

But this was clearly not necessary. Upon entering the space, Hywel handed me two paper information sheets detailing the history of the church, one in English and one in Welsh. On every seat was a Welsh and English Bible, and stacks of Welsh hymn books and bilingual copies of the Holy Eucharist. Even the no smoking sign was in both Welsh and English. There was a memorial plaque for the composer Meirion Williams, who was the church’s organist in the 1960s and 1970s, and several war memorials for Welsh soldiers, one of which had ‘Ffyddlawn Hyd Angau’ [Faithful Until Death] as its heading. It was, essentially, like any other church that you would walk into in Wales, perhaps even more overtly ‘Welsh’, but it just happened to be located more or less on the banks of the River Thames, and within clear eyeshot of St Paul’s.

After ten minutes of soaking up this room as best as I could, I called for Hywel, who had disappeared out of sight, and thanked him for letting me in. I took some final pictures in the hallway of the church of things I hadn’t noticed when I walked in – a welcome noticeboard which also had information about Dewi Sant – and walked into the stark cold London in the bright heart of its winter. The city erupts in sound. St Paul’s glowers down from the right, and the Thames roars past to me left, reminding me in no uncertain terms of where I really am. I walk back to work, but not before sitting on a bench on the Thames path, looking out at the river and trying to reflect on what I had seen.

For many people, I’m sure, it is not especially extraordinary that there are Welsh devotional spaces in London. But I think that some of its significance for me lies in the fact that much of my personal Welsh identity is founded on being away; that my ideas of Welshness have, for my adult life at least, mostly formed while living outside of Wales, in places which do not feel Welsh, where meeting Welsh people or having the opportunity to speak or read Welsh are few and far between, but golden when they arise. Finding these churches and being inside them makes me consider the many generations of Welsh people who themselves lived much of their lives outside Wales, because these churches are among the most stark examples of London’s vast Welsh communities which has settled over the centuries. These churches, and the many more that are no longer surviving, were established to serve the hundreds and thousands of Welsh people that, while they could survive outside of Wales the land, could not do without its spiritual and cultural sustenance. And so they transported it, as best they could, to London.

However, there was something missing about my silent afternoon in St Benet’s church. While I was glad to have managed to cross the threshold of the church, unlike Jewin’s, and find some evidence that it was a lived-in, active and thriving space for community, there was still very little sign of life. Flags, neatly ordered bibles, and information notice boards of an undefinable age, were undeniably Welsh, but also pretty ghostly and unsettling when observed by themselves, with just me in the room. It was like a corner of London, unobserved for so long, had been briefly opened for ten minutes, only to be locked up again until another curious person stumbled across it. Not the case, of course, as Hywel informed me that there are regular services, but experiencing it in such a solitary way seemed to give me that impression. So I resolved next time to find a Welsh church that had some people inside.

And last Sunday, I finally managed to do just that. Capel y Boro, the chapel that first made me aware of the existence of these spaces in London, was advertising on its website that it was hosting a Plygain, which it described as a traditional candlelit carol service. It was happening on 14 January, and I resolved to go.

I had never heard of a Plygain, a word which suggests plygu, to bend (as if in prayer), but, Wikipedia offers, could come from the Latin word pullicanto, meaning ‘when the cock crows at dawn’. Either way, the service is traditionally held between 3 am and 6 am on Christmas morning, and was first recorded as taking place in the thirteenth century, and still takes place in certain parts of Wales. During a Plygain, parishioners come forward to sing carols, specifically ones relating to the crucifixion. Tradition has it that the service continues for as long as the singers succeed in not repeating the same song twice.

Evie and I entered the chapel a few minutes before it was due to start and were each handed a candle and a sheet of paper. We climbed the stairs up to the gallery and saw a room filled to the brim with seated people holding lit candles. We shuffled along, took our seats and lit our candles. The next hour or so was filled with such divine music, as choirs and smaller groups of singers took to the stage and sang in the richest harmonies that I can ever remember hearing. I was reminded that night of the twelfth-century chronicler Gerallt Gymro, and his own descriptions of the beauty of Welsh singing:

When they come together to make music, the Welsh sing their traditional songs, not in unison as is done elsewhere, but in parts, in many modes and modulations. When a choir gathers to sing, which happens often in this country, you will hear many different parts and voices as there are performers, all joining together in the end to produce a single organic harmony and melody in soft sweetness.

This observation has become cliche, perhaps, but it is an observation that nonetheless never felt truer to me than on this evening in Capel y Boro.

The service was punctuated by other songs which the congregation were then encouraged to join in with. Despite not knowing all of the melodies, the power and strength of the other surrounding voices gradually ease you into its movements, and before long you are singing each line with such assurance and strength that it is as if it is the only song you’ve ever known. Singing in a choir is one thing, but feeling oneself elevated by the spontaneous power of an unrehearsed group of people, is an extraordinary feeling, only partially undermined by my constant fear that I would either drop my candle or cause my paper lyric sheet to catch fire.

I realise now that my preconceptions about the Welsh community in London, and how it continues to be served by the Welsh chapels and churches of previous generations, were shaped by my own ignorance and cynicism. There was a desire that I would stumble upon something that would ring true to myself, and tell me something about my childhood and identity, perhaps – but I did not expect to find such clear evidence of a thriving Welsh culture in London outside of Six Nations fixtures at the London Welsh Centre.

I’m not sure what these experiences have taught me, other than to serve as a humble reminder, if ever one was needed, of the cultural reach of the Welsh, and of the depths of its roots in a place like London, where there is such space for your identity to take shape. It has also taught me of the power of the interior, both of the physical buildings themselves, but also of the imagination, the memory. It was memory and emotional and spiritual longing which caused these buildings to be here in the first place, and whether interested in the spiritual significance of these places or not, their cultural significance for Wales and what they represent to those who feel attached to such spaces is immeasurable. If nothing else, they make me feel less isolated up here, this side of the bridge.

I realise that in my two years of living in London, I have only tentatively scraped at the surface of it, the city which continues to surprise and reveal things about its inhabitants that you would not expect. Not that these things are particularly hidden – it just takes an ignited memory, and a deviation from the habits we create for ourselves, to realise that the familiar can hide itself in the most unfamiliar of places.

Rhys Underdown (he/him) is a 27-year-old bilingual writer and musician from Swansea, now based in London. His writing explores his relationship with Wales and Welshness, drawing on the inherent tension of living outside Wales. All images are by the author unless otherwise noted.