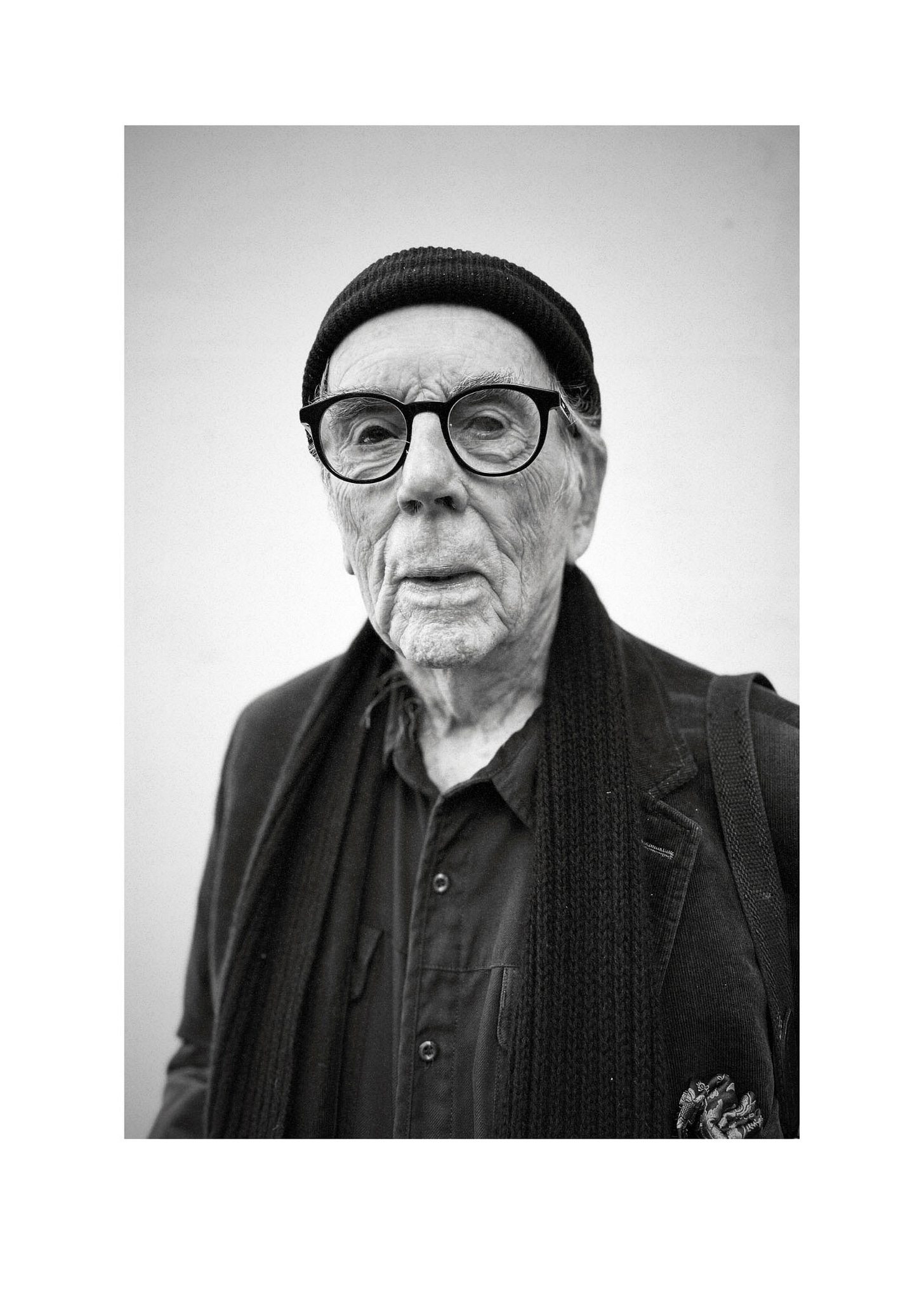

Ideas Worth Pursuing: David Hurn in Profile

Following his Outstanding Contribution to Journalism award at the recent Wales Media Awards, Glenn Edwards profiles veteran Welsh photographer David Hurn

Forty years ago I walked through the doors of the School of Documentary Photography in Newport, not knowing then that those few steps would change my life, as they had changed the lives of so many before and after who were lucky enough to take those steps.

The world-renowned course was founded in 1973 by David Hurn, the recipient of the Outstanding Contribution to Journalism award at the Welsh Media Awards that took place at the Parkgate Hotel, Cardiff on November 15.

The course had such a reputation on the national picture desks that when presenting my portfolio to the wonderful Tony McGrath, then Picture Editor at the Observer, he asked where I was from, and I told him Newport, to which McGrath said: ‘Ah you are from mother’.

The Newport course was the supplier of so many photographers to the industry all over the world, me being one of them, and I am honoured to still call David a friend.

It all started for David Hurn in the officer’s mess while still in the army when he picked up a copy of the magazine Picture Post. He still remembers the date: February 12th 1955.

David was overwhelmed by an image on one of its pages. ‘Suddenly I started to cry really quite violently,’ he explains. ‘It was not just little tears, it was big sobbing.’ The image, taken by Henri Cartier Bresson – a photographer David had never heard of at the time – was of a Russian army officer buying his wife a hat in a department store in Moscow. ‘It triggered a memory of my own father returning from World War II and taking me and my mother to Howells department store in Cardiff and buying her a hat. It was the first memory I had of the love between my mother and my father, [and] I instantly realised that all Russians don’t eat their children. This one simple picture I believed, more than the propaganda.’ The seed had been sown and David Hurn decided at once that this is what he wanted to do.

It was as a freelance he gained a reputation for his reportage, covering the 1956 Hungarian revolution – an assignment he took on with camera in one hand and the instruction manual for said camera in the other. A true case of learning on the job and wanting to achieve. David hitchhiked to Hungary then crossed into Budapest in an ambulance, where he was introduced to the Daily Mail correspondent who introduced him to Life magazine.

His images were published in Life, Picture Post, The Observer and more around the world. Life ensured that Hurn left Hungary before Soviet tanks entered the city. He says: ‘Chances happen throughout our lives – but do we always take them? Sometimes we don’t realize that the things in front of us are chances, opportunities, waiting to be seized’.

This was a time when photographers were becoming celebrities, featuring on television and in magazine pages as much as their subjects. People like David Bailey, Terence Donovan, and Hurn were becoming icons of the fashion led 1960s. David was in the mix, associating with the right people in London, and as a young photographer he featured in two Ken Russell films, A House in Bayswater and Watch the Birdie.

In the early sixties he had a small studio in London, shooting the famous Sean Connery 007 image, gun in hand, for From Russia with Love. But look carefully at that gun. With producer Cubby Broccoli and Connery in the studio the publicist told him they had forgotten to bring the famous Walther PPK weapon. No panic, he told them; he had a Walther, but as a keen target shooter it was an air pistol. David told them to cut the barrel down to size for the poster – but unfortunately they forgot, so tough guy Bond in one of the most famous 007 images is holding an air pistol that wouldn’t kill a moth at 20 paces let alone do a job on Odd Job.

In 1964 he was asked by a friend, Dick Lester, who was about to direct the first Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night to shoot the stills but not for the press. He wanted the images to have a more sociological documentary point of view, to witness the chaos that surrounded the group at the height of their Beatlemania fame. Hurn recalls: ‘During the filming they had the top five slots in the Singles chart and the Fab Four couldn’t go anywhere. Often they were in my car and the police would have to just wave us through a red light because they knew if the car stopped it would be totally mobbed’.

In 1967 he shot the stills for cult sci-fi classic Barbarella, starring leading lady of the swinging sixties Jane Fonda. He became a close friend and held her confidence enough to be asked to photograph the sets of The Dolls House and Spirits of the Dead in the early seventies.

On October 21st, 1966 Hurn was in a car with fellow Magnum photographer Ian Berry when they heard of the tragedy in Aberfan on the radio. Turning the car around immediately, they travelled to the village, among the first photographers to arrive at Pantglas Junior School, as dusk was falling. Hurn recalls ‘miners digging in this crap to try and get their children out.’

Grieving parents did not want a photographer around, but David knew he was performing a job that might prove to have not only historical but legal significance. ‘Nobody can ever say it didn’t happen or that it wasn’t as bad as it was seen to be,’ he says.

Speaking in the House of Commons on Oct 26 1967, after an investigation into the disaster, Arthur Pearson, MP for Pontypridd, talked about how improper management of the site had led to a dangerous situation. Mass shale was piled up on top on the hill overlooking the school. He referenced images from the press of the time showing this: ‘We have too lightly passed over this danger of water. Hitherto, sufficient weight has not been given to the mischief which big rainfalls can create. There have been instances during the past week, and there are photographs which show that the bases of large tips run adjacent to mountain streams which flood and wash away the sides. No attempt has been made to protect any tip by walling against erosion. Will the Minister of Power give attention to it? The photographs have appeared in newspapers for all to see these roaring streams, and no attempt has been made to wall the bases of the tips to protect them against erosion.’

David Hurn and Ian Berry took some of the most poignant images of the time and they were used in Parliament as evidence of the disaster and played a small part in helping bring about change and preventing another such tragedy. ‘It’s a really good example of photography absolutely justifying being done,’ says Hurn.

Berry and Hurn received a note from Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier Bresson saying their images from Aberfan were Magnum at its best. Hurn was a Magnum nominee at the time from 1964 but was made a full member in 1967.

Being of Welsh heritage, though born in Redhill in Surrey, David was raised in Cardiff, and his proximity to the story helped him decide to return to Wales from London four years later.

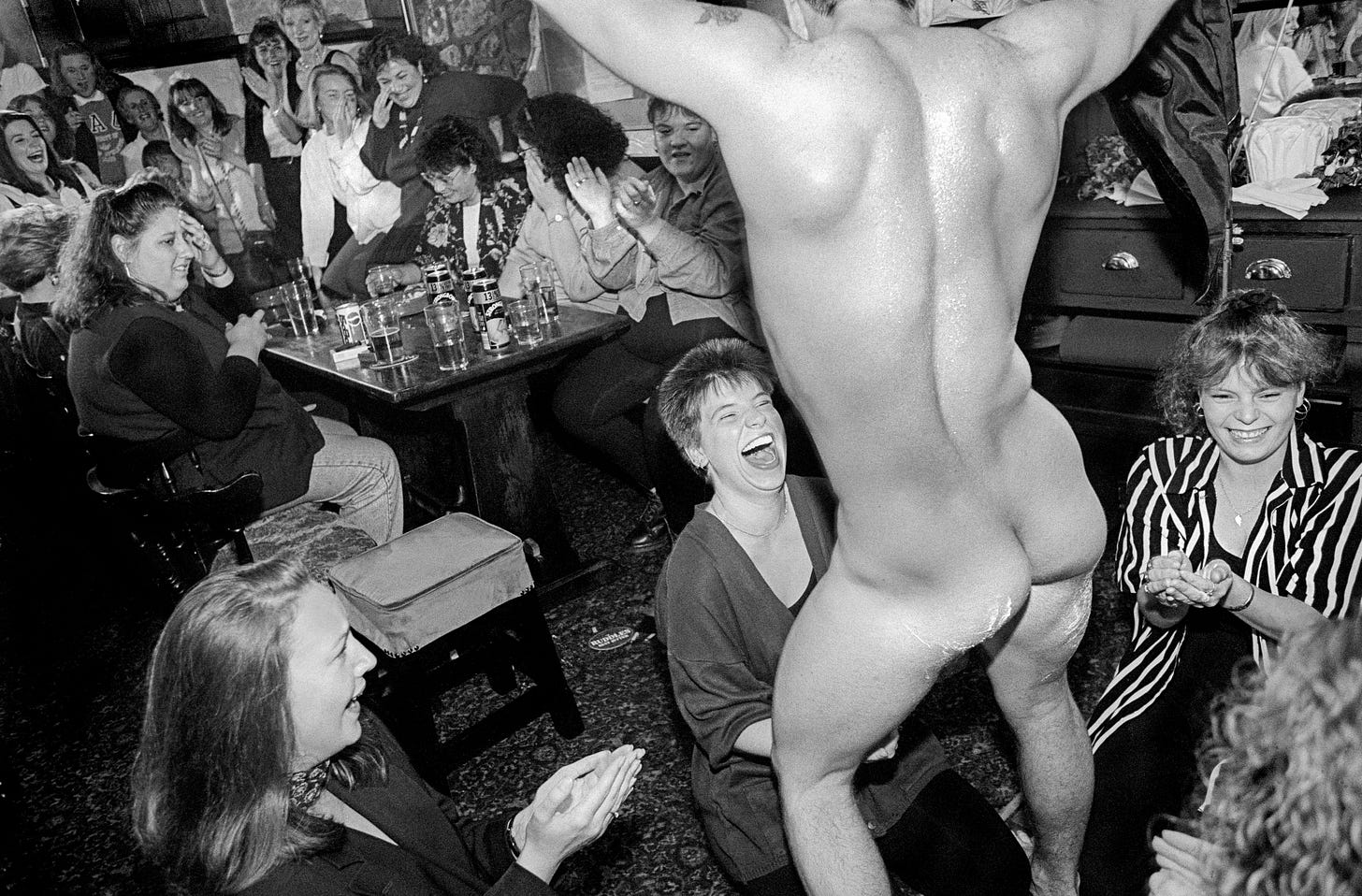

It was around this time Hurn turned away from covering current affairs, preferring to take a more personal approach to his photography and it is his book Wales: Land of My Father, first published in 2000, that truly reflects his documentary style – and records the cultural changes that have swept across Wales since the end of the 1970s.

His gentle style of documenting the world influenced me as a photographer, understanding how to show it as it is. The thought process – not just taking images for today but for a hundred years’ time and beyond; to show the simple things, the hair style, the fashion, the culture; the fraction of a second image capturing the imagination and interest to raise awareness on important issues and educate. In these times of AI the truth is being challenged, but photographers like David Hurn will always be there and his images believed.

Through the Newport years and to this day he has continued to document life in Wales and beyond in his unique style. An example taken from outside Wales is from his time spent around Phoenix, Arizona. Arizona Trips was published in 2017. These trips were also visits to a good friend, the late Professor Bill Jay, who collaborated with David on a very successful textbook. Many consider On Being a Photographer the bible of documentary photography learning.

In 2001 David openly says the most important picture in his lifetime was taken. It was taken where the sun doesn’t shine if you know what I mean, and helped diagnose David with colon cancer. The picture found the problem and saved his life, demonstrating the true power of photography.

It was on my return from Sierra Leone after covering the first free election after twenty years of civil war that I showed David some of the images from the trip. He liked one in particular of celebrations on the top of a car in Freetown, where in the centre of the flag is the word ‘peace’. It was a very poignant image considering the history of the country. He asked if I would like to swap the image for one of his own. Of course, I felt honoured to be asked and agreed: not knowing the history or reasons.

During his long career David had the best idea of swapping images with the greatest photographers from all eras (I am not putting myself in this bracket). From Henri Cartier Bresson to Martin Parr, Don McCullin to Eve Arnold. As Parr himself has said: ‘He has produced a concept that is so deliciously simple I wonder why more people haven’t done it. He has built a collection of photographs by exchanging his own images with those of other photographers’.

This Swaps collection, including the flying flag from Sierra Leone, has been exhibited at Amgueddfa Cymru in Cardiff and now sits in an archive donated by Hurn to the National Museum of Wales for future generations to enjoy.

In 2016, now in his eighties, David found social media and opened an Instagram account. Using the account to share constructive photography ideas and advice, at last count he had over 80,000 followers. On Instagram is another book of Hurn images, taken from his relatively new association with the social media platform.

With more publications due soon, there are now 14 books and multiple zines, the latest on Swifties (fans of Taylor Swift) on the streets of Cardiff before her concert just a couple of months ago. David’s insatiable curiosity continues to fuel his work today and reinforces something he says regularly: to be a photographer you must have a good pair of shoes.

With a longstanding international reputation as one of Britain’s leading documentary photographers and now in his nineties, David Hurn continues to live in Tintern in the Wye Valley and to work across Wales.

Way back in the 1970s, David wrote: ‘I believe that in a society in which every individual opinion counts, photography at its best has a unique ability to instruct, to help make alternatives intellectually and emotionally: to spotlight foolishness, to bring people together, to break down barriers of prejudice and ignorance, and show ideas worth pursuing. I have not changed my mind.’

On occasion I have helped with lifts, to get to the latest Hurn image for his new landscape book. We always know where we are going and the picture that is required, but once taken and driving back home there is inevitably a further request.

‘Do you think I could be a bore and ask if we could go back a mile? I have just seen something interesting.’ David Hurn will never stop looking, and will always be relevant to Welsh photography – and more importantly to Welsh life and its history.

Glenn Edwards is a photojournalist who has worked on over 100 foreign commissions, more than eighty in nineteen African countries, as well as Chile, Ecuador, India, Albania and Bosnia. He is founder and Director of The Eye International Photography Festival, and a good friend of Cwlwm, for whom he has worked on various projects.