Floating between two tides: poetry as art, poetry as lived experience

Rachel Carney wants her poetry to be encountered on its own terms, but also to reflect what it is like when dyspraxia affects every area of your life

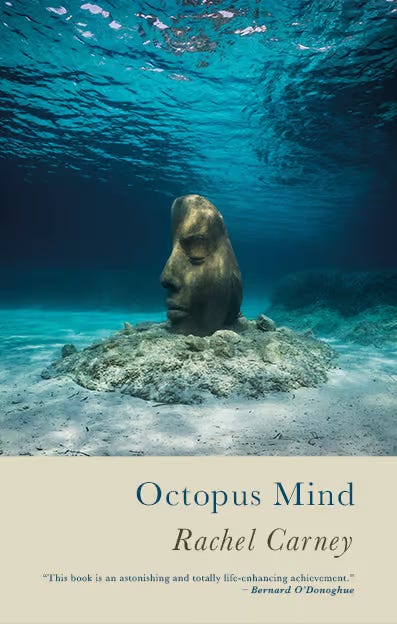

My debut poetry collection, Octopus Mind, was launched last summer by Seren Books. It now floats out there, in the poetry ocean, waiting for the reviews and opinions, the comments and the likes. But there is a tension that pulls at the heart of my work, between the desire to communicate and represent, and the desire to evoke and engage. These things are not entirely separate, but when a poet writes about their lived experience, that’s when the tension flows in. Will people read these poems as straightforward confessional accounts? Or will they engage with each poem on its own terms, as something that is both crafted and felt, both dialogue and experience?

On the one hand, I do want to represent, through my collection, something of what it is like to be neurodivergent. I want to convey the complexity of my own experience, and to forge a sense of connection between the reader and the elusive truth that lies at the heart of each poem. I want the poems to speak for me, and for others like me.

On the other hand, I want my poems to speak for themselves. I want each poem to be open, to invite the reader to climb inside and make it their own, as I become a blurry, distant director, fading into the background. Sharon Olds, whose poems often seem to emanate from personal experience, describes her work as ‘apparently personal’ rather than ‘confessional’, and Emily Berry has similarly claimed this phrase as a way to describe her own grief poems. The process of crafting and editing always creates a distance between the poem and its initial source of inspiration.

When I was putting the collection together, I initially grouped all of the poems according to topics such as ‘neurodiversity’, ‘art’ and ‘unrequited love’. But this approach was never going to work. I’m not saying this is the wrong approach for everyone. In my case, it just felt impossible to draw a line between different subjects. Life cannot be categorised so easily.

I have recently been reading three other collections by neurodivergent poets, all published by Nine Arches Press. The Oscillations by Kate Fox, Be Feared by Jane Burn and Bunny Girls by Angela Readman each contain a mix of poems exploring a range of different subjects, including poems inspired by these poets’ experiences of autism. And in each of these books, the poems are not grouped together into defined sections. Like my own collection, there are some poems that are flagged up as clearly inspired by the writer’s neurodivergent experience, and others that are less clear. Kate Fox has chosen to list the poems that ‘touch on neurodiversity’ in her notes section at the back of her book, while Angela Readman and Jane Burn have left the reader to make their own observations. I felt that such a list would be impossible in Octopus Mind, and I hope that reviewers are not afraid to respond to the poems as they find them.

Dyspraxia affects every area of my life, so it made sense to scatter these poems throughout the collection. And yet there is far more to my poetry than neurodivergence. I’ve been inspired by all sorts of material, from nature documentaries and works of art, to Covid-19 and toothache. My poem ‘The clues were all there, strewn out along the shore’ attempts to convey this mixed-up-ness by following a treasure hunt, where the letters of the word ‘dyspraxia’ lie tangled up among the litter, the shells, and the driftwood of life. Not only does this evoke the strangeness of self-diagnosis, it also (I hope) reinforces the fact that neurological differences such as dyspraxia are not easily definable, nor easily understood, even by those of us who are neurodivergent.

I know that many other writers grapple with the tensions I’ve described above. They offer up their new-born poems to the world as finely wrought, living, breathing entities that are both entirely connected to, and entirely separate from, their creator. I hope that we can all allow the poems we encounter to be everything they can be. To communicate the nuance of lived experience, but at the same time, to become their own free-wheeling, ever-changing, complicated selves.

Rachel Carney is a creative writing tutor and PhD student based in Cardiff. Octopus Mind is published by Seren Books.