Even the ghosts: final days in Russia

Cwlwm continues to mark the second anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, with our reporter's story of the Moscow bookshop Western expats left behind

The little secondhand bookstore of St. Andrew’s Church was a place of endings from the beginning. I was introduced to it in November of 2020, by a British man who is allowed to keep his theatre props in a tiny office in the basement, in return for delivering a children’s play in the summer. There’s also a kindergarten down there, a room full of secondhand clothes, and a security guard who sleeps in a long narrow room at the bottom of the perilously steep winding stone staircase.

My Siberian theatre had died. Killed by Covid restrictions. And in a spur of the moment decision, I had moved to Moscow, alone. I lived in a capsule hotel for three months while I scrapped together the cash needed to rent a Moscow flat, where my wife and daughter could eventually join me.

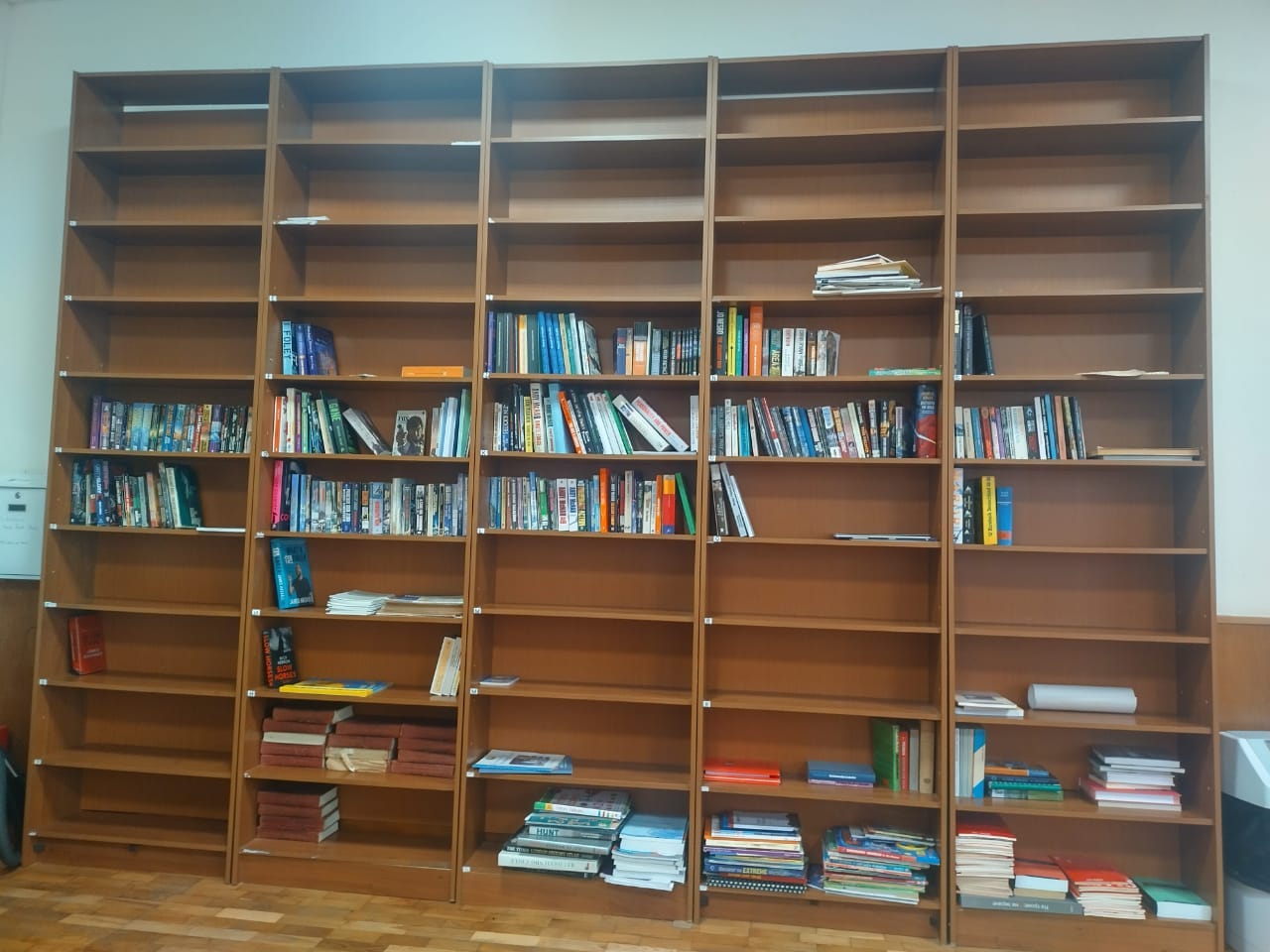

The bookstore is directly opposite the top of the staircase, hidden behind a set of double doors, laden with uncountable coats of hastily applied yellow paint. When I first opened those doors, it was like walking into a bookshop no-man’s land. It wasn’t your usual secondhand store. Entire shelves had rows of books that somehow seemed connected. They were siblings. They had stood side by side on other shelves, in other buildings. Books hadn’t been organised according to genre, title, or alphabetical order. They’d been placed according to their arrival.

Occasionally I’d walk in there on a Saturday morning and find a pile of boxes on the floor on the right hand side of the shelving. Either someone had died, or someone had left for the West, and was never coming back. Usually the latter. Instinctively, you knew they hadn’t gone east. Because if they’d gone that way, they wouldn’t have left the books. There was always the train. Heading west meant planes and luggage weight restrictions. No, they’d always go west. You could tell if a whole family had left by the number of kids’ books among the trashy spy novels and Wordsworth Classic editions with those horribly uninspired black covers. Lives, whether through death, or moving back, had ended here.

A first edition Tinker Tailor with original dust jacket, dominoes on the front; unfortunately, in Dutch. I found myself perusing the shelves every other weekend, not so much to look at the books, but to wonder about the people who had owned them. How long had they been in Russia? What had been the final straw? Where had they returned to? The books weren’t just books, but fragments of people’s minds. Evidence of their tastes, desires, fantasies, and lives lived out. I got to know them, just a little, having never known any of them. The books were the only proof that they had lived. Only their ghostlike presence remained, as people I imagined out of the collections they’d deposited in their final days in Russia.

I think it was at the end of 2022 when I was told by one of the church volunteers that the woman who had run the bookstore had herself left Russia. She’d been there for decades apparently. The bookstore fell into disarray quickly after.

It turned out she had actually been vetting the books the whole time. Now, in her absence, shelves contained random notepads full of shopping lists, and tattered copies of Reader’s Digest nobody would ever buy, even though the church only charged 100 roubles for anything. I stopped visiting.

Last week the same church volunteer sent me a text: the British Ambassador had left, and would I like a first look at the box of books he’d dropped off? I delayed my visit by a few days. I had to prepare myself, as strange as that may sound.

When I arrived, I think either the last few remaining church volunteers had had first pickings, or the Ambassador hadn’t been much of a reader. The shelves were mostly empty, save an obligatory John Le Carre Agent Running in the Field, the Penguin edition of the History of the CIA, and a well-thumbed 1984. I packed them into my rucksack and sat on a chair near the opposite wall from the shelves. There wasn’t much of anything left.

The religious books that had once stood on a separate freestanding shelf unit were now mixed in with a handful of Italian furniture magazines on the main shelves. Most of the books I had come to know were long gone, even the old Dutch Tinker Tailor had disappeared. I was alone, in the sense that those fragments of people, whose books had once frequented the shelves, were no more. And no more were coming. There was no one left to drop off any books, no one to arrange them, and almost no one left to buy them. Even the ghosts had fled.

The author of this article wishes to remain anonymous.