Easter in Wales – what happened?

Richard Parry takes us on a journey from the Roman amphitheatre in Caerleon to St Illtud's Church in Llantwit Major, via pubs, prisons and poems, in search of answers

It’s not every day you’ve got somebody in your back garden building crucifixion crosses.

Tony and I had met a year earlier. A series of joiners had not come to replace a failing front door and I stopped a man driving down our street in a van with timber lengths strapped to the roof.

‘You’re not a joiner are you?’

‘No, I’m putting up For Sale signs. Why, what’s the problem?’

I told him about the broken front door.

‘There’s a guy in our road who’s a genius with wood. And he’s reliable.’

The next night Tony travelled on the bus from Victoria Park in Cardiff. We’ve been friends ever since. He replaced the door, made a kitchen shelf with a piece of wood from a scrapyard in Tremorfa on the other side of the city, and when I asked him to make two full-size crucifixion crosses he said, Very well, yes, ok.

Crucifixion today is principally an Easter word, but it was an all-year-round fixture 2000 years ago. This common Roman judicial state torture may have been adopted from a Carthaginian practice. As far back as the sixth century BC it is recorded as a mass execution method and was only abolished in the fourth century AD by the Roman Empire. Crucifixion reigned for a thousand years.

The early Christian martyrs Julius and Aaron were probably killed at the Roman military settlement of Caerleon, just north of Newport. Records of everyday military and judicial deaths under Roman occupation in Britain are lost, but the names of Julius and Aaron are carried to us in Wales through generations of local remembrance, then an inclusion in early medieval literature, and finally written into history books. A hill suburb in Newport, St Julians, still carries one of their names.

We strapped Tony’s two full-size crucifixion crosses onto the roof of my car and drove to Caerleon’s Roman amphitheatre. Visited by many today, in this place human death, misery and diminishment have been regular, popular entertainments.

It was just before sunrise. The auditorium still forms a theatre. Placing on the floor of the arena one cross representing Julius, and one cross representing Aaron, we stood in silence. Day broke. This wasn’t historical reenactment. There’s no evidence that these two men died in the amphitheatre. They may have died in the barracks. Perhaps they weren’t crucified. Killed another way, perhaps.

We simply erected the crosses as symbols. Remembered their names. We only know that Aaron and Julius were executed in direct connection with a man from the East of the Empire who had been nailed to a Roman cross. This very old story about Aaron and Julius, in the Usk valley landscape, is an intimate and violent opening for us on to the Christian story in Wales.

But there’s a gap.

What can we possibly make of this today? Do crucifixion narratives really have any relevance for us? The Roman army left Britain 1600 years ago and the Roman Empire abolished Christian persecutions in 313 AD. Shortly after, this same faith, featuring at its centre a crucified man, was fully adopted by Roman rule and has been handed down to us as a state religion.

In 1998 Mark Cazalet was commissioned to paint the Roman crucifixion of Jesus set in contemporary London. The result presents detailed modern London scenes showing the trial, sentencing, public journey, execution and resurrection of the Easter story. Venues include Wormwood Scrubs Prison, Portobello Road Market and the Penguin House of London Zoo. In past years if you wanted to see Cazalet’s fifteen Easter paintings you’d visit a cathedral, but this year the works have been individually placed in pubs, cafés and shops across the Vale of Glamorgan in south Wales.

Gone are Roman helmets and dusty-robed onlookers. On the walls of Welsh pubs the Jesus represented in the western art tradition becomes a series of fallen figures, shaded helplessness, the object of pavement-kicked hatred, the hollow face of a man nailed to a fence in a city scrapyard; betrayal to violence, a beaten figure dragged through Portobello market. The artist Cazalet uses the paintings to take this contemporary city of disregard, degradation, invisible suffering, ignored humanity, torture and abandonment of care, and joins it to the passion, degradation and transformation of the Easter story.

Yes, it’s not exactly your traditional pub crawl, but five hostelries in Cowbridge have held these paintings on their walls in the weeks before Easter. The art has provoked discussion and attracted visitors. In Llantwit Major a stark canvas showing impassive faces of London Underground commuters on a station platform hangs in the foyer of the Filco Supermarket. Cazalet painted the works seven years before the Metropolitan Police execution in 2005 of an innocent man, Jean Charles de Menezes, on the tube at Stockwell.

The display of these paintings is organised by the New Library in Llantwit Major, part of work to examine the story of Easter in the midst of contemporary life. The idea is called Perspectives on the Passion.

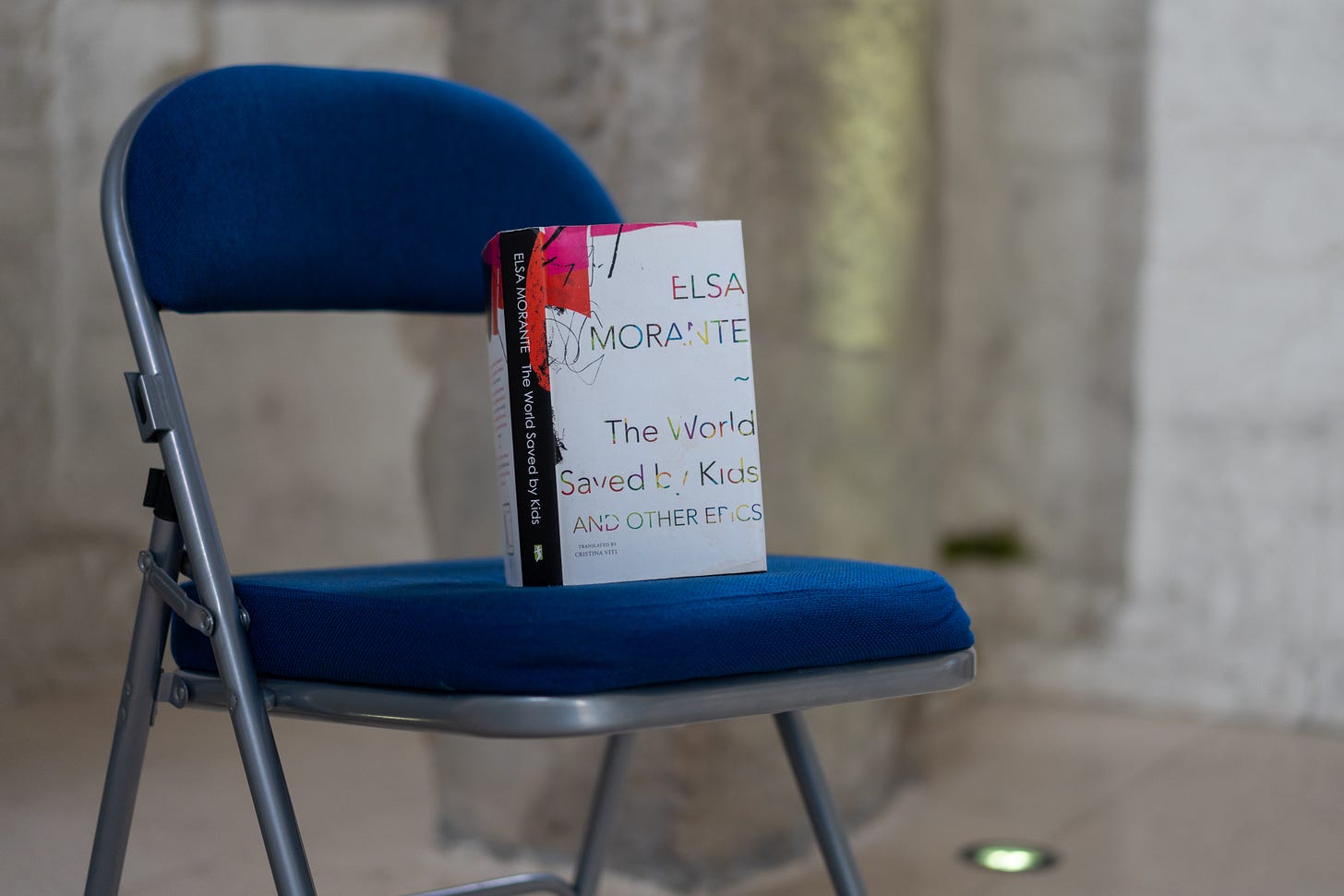

On Good Friday the project gathered all Cazalet’s London paintings into the church at Llantwit Major and held a public reading of two sections from Elsa Morante’s 1968 youth revolution poem The World Saved by Kids. Pairing the Cazalet Easter paintings and Morante’s dramatic poetic call for young people to grasp the world afresh adds a further layer.

For the first poem a father and his fifteen-year-old son encounter a man being taken by the military for execution whilst walking to work on a building site on the edge of modern Rome. When the condemned and beaten man falls, the young boy intervenes. In the third poem we encounter a schoolgirl living in Third Reich controlled Berlin. When an announcement is made that all Jewish people will be compelled to wear a yellow star, she decides to act.

These poems from The World Saved by Kids were read either side of the traditional midday Good Friday liturgy at St Illtud’s, a church that stands on a site of 1500 years of Christian scholarship. The work is an attempt to break open renewed public interest in the trial, condemnation, torture and execution of Jesus. The paintings and the poem clearly do this. There has been curiosity, interest, compassion, distress and deep engagement with the Easter story – the clear connection of its suffering and injustice relating to our world today.

But there remains a glaring obstacle. How should our contemporary life gaze on the fifteenth painting? We’ve left this canvas hanging in the White Hart pub in Llantwit. It shows the resurrected Jesus, on the fields of Wormwood Scrubs, talking to dog walkers.

Our lives have been strongly shaped by science and secular humanistic thought. We understand suffering and injustice, but a resurrection narrative – a new life out of death – is a dimension beyond our popular and institutional culture. To explore this our south Wales project has been celebrating the writing of John Rogerson. He’s a scholar of international renown for research on the contemporary relevance of the Old Testament, and also an Anglican priest. In his short book Perspectives on the Passion Rogerson sets out how, after a thousand years, a change came about in the church’s view of the meaning of Easter and the death of Jesus.

For the first thousand years of the church, which includes the period that Julius and Aaron were at Caerleon, the story of the arrest, trial, beating, torture, humiliation and crucifixion of Jesus was experienced as something that engaged with, and defeated, the power and structures of evil. It was understood as a divine way of freeing human beings from the bondage of evil. Yet, a thousand years later, with feudal allegiance and honour structuring and dominating most of Western medieval society, the church began to gradually assume that humans owed this type of feudal allegiance to God. The meaning of the death of Jesus changed, and people were taught that the death of Jesus paid a debt to satisfy God’s honour. This view is still widely held. Modern churches have inherited this feudal legacy.

People not connected with today’s church have recognised Jesus in the Cazalet paintings as a figure who bears the suffering of humanity. It is a suffering that transcends all difference in human identity, across all cultures, across history. Science and logic get stuck at the resurrection story but cultural history reveals that poems and art move narrative and meaning through such blockages in unusual ways. When material facts are examined, everyone is perplexed. Answers elude us. Nails. Betrayal, death. No further conversation is possible. But shift to focus on the person bearing the pain. The history of the person. His character. His mission. His compassion for human suffering and his carrying of it. For a thousand years this person, tortured on a crucifixion cross, was thought to have broken forever the hold of evil over human culture. He is a significant subject.

So today the question may not be so much, What happened? But rather, Who happened?

Richard Parry is the director of the New Library, Llantwit Major and a scholar in residence at the Cambridge University Centre for the Study of Platonism. The World Saved by Kids, by Elsa Morante, translated by Cristina Viti is published by University of Chicago Press. Perspectives on the Passion, by John Rogerson is published by Beauchief Abbey Press.