Down Your Local?: A life in public houses

Following a recent exhibition of his photographs of Newport pubs, John Briggs recounts a lifetime's transatlantic love affair with the charms of 'the local'

local

Brit. colloq a local public house

US a local branch of a trade union e.g. Local 118 (Ironworkers)

The Concise Oxford Dictionary

‘England and America are two countries divided by a common language,’ quipped George Bernard Shaw. Little surprise then that I didn’t know the Brit. colloq meaning of the term ‘local’ when in 1964, at the tender age of 17, I first arrived in south Wales to attend the international sixth form at Atlantic College. Little surprise either that I had scarcely any awareness of the local bars in my hometown of St. Paul, capital city of Minnesota. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to cross their thresholds anyway, not until I was 21, the legal drinking age in the USA.

But as I settled into life at Atlantic College, and began to explore the nearby communities, it didn’t take me long to become aware of ‘the local’ in the British sense. Even as sixth formers, we had one.

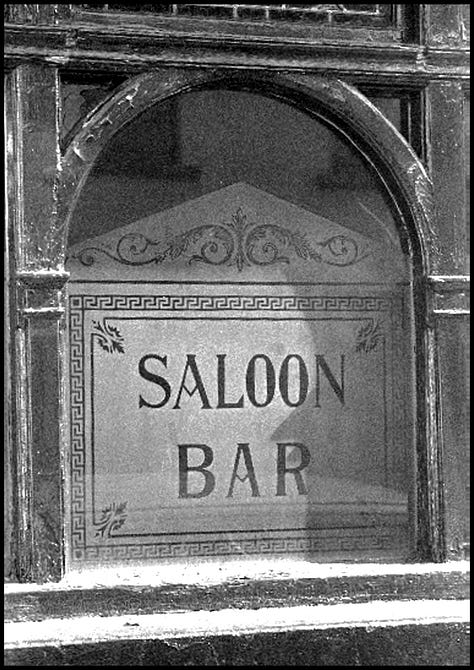

Llantwit Major was just under two miles from the college – an easy walk and an even easier hitchhike when just about any driver would stop and pick you up if they saw you wearing a college scarf. Our local there was The Globe – and the landlady, clever and sympathetic as she must have been, had put aside a small ‘lounge’ for our use: lounge as opposed to ‘public bar’, ‘smoke room’, ‘snug’, ‘jug and bottle’ – each designating different rooms in a way that is unknown in American bars.

The lounge was reserved for us chiefly because it had an old console hi-fi and we could play our records on it – 45s or LPs. Listening to the music of the times – Beatles, Kinks, Animals – was our chief pleasure, along with conversation more than drinking. Many of us were underage anyway, so getting served shandies and soft drinks under the landlady’s benign and watchful eye was just fine by us. Never was an ID card or passport asked for. A far cry from American bars where even going you would immediately arouse suspicion, a demand for ID, a refusal to be served and an invitation to leave and not come back. For those of us who did drink, Hancock’s bitter and mild was on handpump at 1s 3d a pint. Warm and practically undrinkable to my immature, adolescent palate, keg beers like Hancock’s Barley Bright and Ski lager, cold and always predictable in taste, had more appeal.

The public bar was the preserve of the local patrons and we seldom went in there, except to buy a drink before going back to our designated lounge. Walking past the window of The Globe one day before the Christmas holidays I peered in to see two gentlemen having a pre-Christmas drink. They were singing and swaying back and forth on the wooden settle next to the bar, oblivious to the fact that they had regurgitated a large quantity of their Hancock’s bitter over their jackets, shirts and trousers and on to the floor. The landlady didn’t seem too bothered either! Needless to say I didn’t feel inclined to stop in for a pint.

Nonetheless, the idea of ‘the local’ had entered my head and would always remain: a place where, even as a teenager, I could feel comfortable, listen to music, chat with my friends, even get to know ‘the locals’ over a drink. The one drawback was that there were hardly any girls. Females in Welsh pubs were a rare commodity back in 1965.

After A levels in 1966 and leaving Wales, it was back to a pub-free existence as a student in my American homeland. I spent four years at the University of Minnesota doing a French degree, and, significantly, worked outside of classes for the Minnesota Daily as a student photographer. As for refreshment and socialising after my academic labours, the phenomenon of the coffee house on and around the campus was one way of quenching the thirst of under-21s such as myself. It had been so since the Beat days of the 1950s.

A nineteen-year old Bob Dylan discovered this when he enrolled at the same university in 1959 and began to frequent the Ten O’Clock Scholar at 14th Ave at 4th St SE in Dinkytown, the Minneapolis equivalent of Greenwich Village. Live music and the folk revival were positively up his street as he became a fan and learned the licks of established folkies such as ‘Spider John’ Koerner, leaving his academic courses second fiddle.

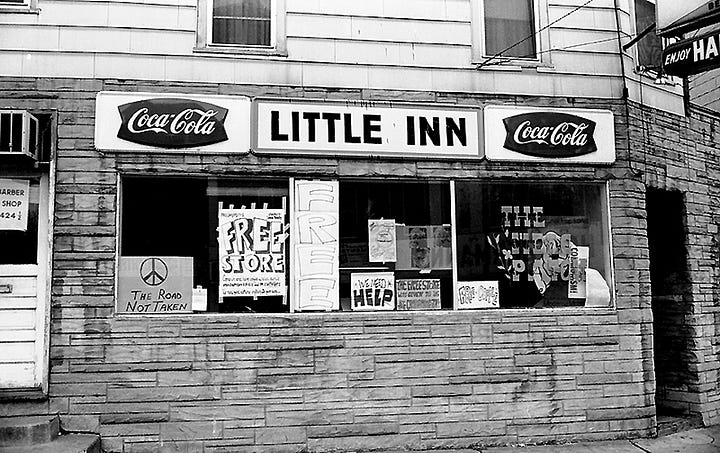

By the time I arrived at the university in 1967, established venues such as the Scholar had moved from Dinkytown to the bohemian quarter and epicentre of the Minneapolis 1960s counterculture, the Cedar Riverside area of the West Bank (of the Mississippi River). A Daily assignment took me both to the Scholar and the Free Store, which had not long before been a bar – the Little Inn. Two ‘locals’ there had stopped in to shelter from the Minnesota winter and get a free coffee. Along the same street, Cedar Avenue, the bars came alive at night: sizeable, open room affairs, tap beers (no real ale that’s for sure) and live music or jukebox. Right on.

Years later, photographing the features of hometown taverns, I would find that the usual watering hole was pretty devoid of distinctive architectural features: big plastic signs advertised beer, food, pool table, pull tabs, with the sign maker’s skill limited to the most basic illustration on a lightbox meant to shine at night. Food could be interesting though. The ‘booya’ at Billy’s Victorian Bar in St. Paul is a meat stew, originally brought over to the northwestern Wisconsin by Walloon Belgians and popular in the Midwest. And so my visits to bars once I turned 21 were the usual student haunts around the university campus – but none were quite like my experience of The Globe back in far off Llantwit Major in Wales.

Graduating with a French degree, a passion for photography – with some experience of photojournalism – and coming to the end of a two-year stint working in a local hospital in 1973, I had no career prospects; not until I discovered that teaching jobs for language graduates in the UK were in much greater supply than in Minnesota. Successfully applying for a place at University College Cardiff to do a PGCE, no longer would Wales be a distant memory.

I packed my bags and headed back to Cymru in early 1974. Accommodation was with a friend from my Atlantic College days, still a student himself. Nearby were other classmates of his and, not surprisingly they had a local: the Claude Hotel in Albany Road, Cardiff. Suddenly it was like being back in the 1960s and the Globe in Llantwit Major. A friendly, mumsy barmaid: ‘Alright lovely boy, what can I get you? A pint of Whoosh? There you are my darling, that will be 16 pence please.’ A comfortable, stylish oak-panelled lounge, lively public bar, a convivial community gathering place, even an off-licence to buy a flagon to take home after shut tap at 10.30.

I wasted no time photographically exploring Cardiff, the newfound city – much less affluent, in decline certainly, but with an architectural character lacking back home in St. Paul. In 1970s Cardiff, the area around the Hayes and Mill Lane was a magnet: a jumble of streets with antiquarian book dealers, a dart shop, leather goods, a jazz club, a delicatessen, an open-air market. There were no shortage of fine exteriors: the Salutation’s symmetrical row of black and white Romanesque arches; the green and gold enamelled-tiled facades of the Golden Cross and the Vulcan (now reconstructed at the Museum of Welsh Life at St. Fagan’s), the Glastonbury Arms aka the White House, with its white tiles from top to bottom. All with leaded glass windows incorporating the Brains blue and white mosaic motif. Patrons and licensees didn’t mind being photographed: the landlady of the Salutation, two lady patrons in their 1970s finery in the Golden Cross.

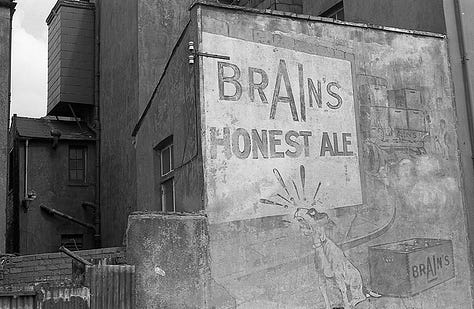

And what of Tiger Bay? Would I find it to be the reputed notoriously dangerous place, full of dodgy pubs and clientele? Not at all. Butetown, its featureless new-builds dominated by two tower blocks, was already showing wear and tear – a decade on from having had its Victorian terraced streets unceremoniously replaced. Two modern estate pubs, the Bosun and the Paddle Steamer, failed to arouse my curiosity. But as you crossed the bridge over the disused Junction Canal and took a few steps down to the former towpath, a unique piece of the sign painter’s art advertising Brains Honest Ale had managed to survive.

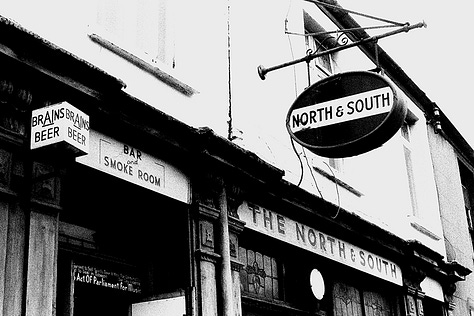

In the Docks residential area, a ghost-town of boarded up streets, there were still a few signs of life on as they awaited the same fate as Tiger Bay. In George Street The Cardiff Castle still had BRAINS worked into the brickwork of its gables. In Louisa Street, at the North and South, where boxer Jim Driscoll used to train in the ‘blood kitchen’ cellar, the beer engines and bar fixings were being taken away just as I arrived, but a lovely ‘Jug and Bottle’ stained glass sign hadn’t yet gone. In Harrowby Street, the New Sea Lock, where I had my stag night in 1981, Danny Whelan continued to serve the locals until the building of the Butetown Tunnel caused it to subside, resulting in its demolition.

Although a foreigner, I too could feel a sense of loss, a despondency when committing to film those last pubs in local streets now only to remain in photographs.

My first teaching post brought me to Newport in 1976, but I didn’t turn my photographic attention to the town until well into the eighties, when marriage and children meant that my camera was most often pointed at family.

In 1995 that changed radically when author, teacher, Newport historian and friend Alan Roderick asked me to take photographs for his book The Pubs of Newport, published in 1997. Its scope was extensive, taking in the inner-city areas of Maindee, Baneswell and Pill but then going beyond – to the suburbs and housing estates of the town. I first lived in Maindee, where once again, a traditional backstreet pub just up from Maindee Square, the Crown, was a welcoming boozer. You had crib players on a Saturday morning, shove ha’penny board, darts – or you could just sit and talk or read the paper. On Maindee Square, a cluster of pubs served the local clientele: the Royal Albert, the Carpenters, the Globe, the George, all modest to look at – but one pub really stood out among local streets named after English cities: the Hereford Arms.

Newport – having developed and enjoyed the same kind of maritime prosperity not far behind Cardiff in the late 1800s – had roads linking its docks directly to the town centre. Dock Street dates from the 1830s and provided the link between Newport and its first Town Dock, eventually running all the way to High Street. Lower Dock Street is equivalent of Mount Stuart Square in Cardiff, the location of choice for shipping company offices, ships brokers, colliery offices, consular offices, anything to do with Newport’s bustling import and export trade.

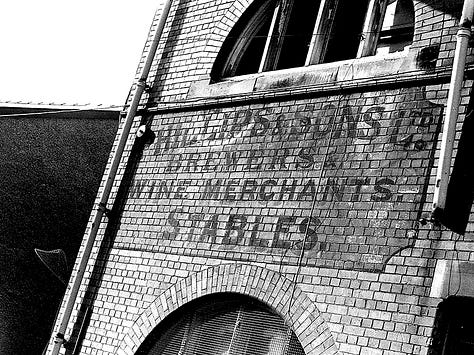

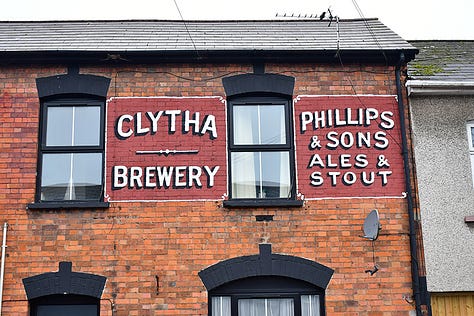

Public houses of course were part of the scene, as was Phillips and Sons Dock Street Brewery (1874). Remains of the licensed trade in Lower Dock Street are now limited to the re-lettered frontage of the former Vulcan pub. The Blaina Wharf, opened in 2015 has been sited near the partly restored town dock entrance, a reminder of Newport’s maritime glory days. At Penner Wharf and the entrance to the dock, Phillips & Sons Malthouse remains, as do the former stables in Mellon Street.

It was along the town-to-docks Commercial Street, Commercial Road, Alexandra Road trajectory that I photographed and frequented, in the mid-nineties, many pubs to grace Alan Roderick’s book. Starting at the top of High Street and nearest Newport castle, two pubs both claim to be the oldest in Newport: the Carpenters Arms and Ye Olde Murenger House both date to the fifteenth century. A green plaque on the wall claims that Carpenters was founded for and by carpenters in 1403. A venerable oak beam in the Murenger claims 1438 as a date of origin. Both have important historical links to the Chartist uprising in Newport in 1839 – the Carpenters as a hostelry where a young Chartist messenger from Bradford stayed after unsuccessfully trying to persuade local leader John Frost to delay his march on Newport; the Murenger was owned at one point by Frost.

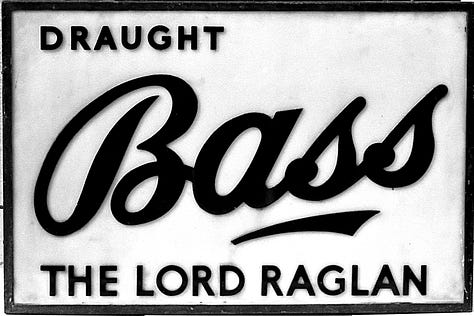

Commercial Street in the 1990s had its fair share of pubs, most of which have closed since. The Albert, famed for its middle bar and its Bass, the Talisman (originally the Isca Inn, 1872), refurbished in recent years but seemingly closed now, the Welsh Prince (originally the Oddfellows, 1848) and perhaps the most notable of the lot, the Hornblower, originally known as The Exchange. The ‘Blower’ was noted for its bikers’ fraternity; even Hells Angels were known to pay a visit and it wasn’t unusual to see a row of Harley choppers parked outside. The pub was demolished in 2018 and replaced by a block of flats.

Against the tide of pub closures however, the Alexandra – not to be confused with the now defunct Alexandra Inn in Commercial Road – opened in 2021 by a resurgent Rhymney Brewery, and serves a city centre clientele. You might say that it compensates for the lost Lord Raglan, a favourite Bass watering hole, which stood very near the same spot until it was demolished in 1974.

And where Commercial Street ends at Mariners’ Green, at the corner with Kingsway, there still stands one of the most ornate pub buildings in Newport, the King William IV, the ‘King Billy’ (1850). An imposing baroque-ish four-storey triangular building, its decorative facades face both Commercial Street and Kingsway, each level quite distinct from the one above or below, with prominent bays of Portland stone. A stone balustrade and balconies at the top storey crown the whole affair. As with so many other premises it dates from Victorian times and must have impressed many a sea-faring visitor to Newport coming up from the docks. Across the green with its Merchant Navy memorial column resides the more modestly proportioned Golden Hart (1872), identified by a distinctive statuette of a deer in its own niche high above the entrance. When the Ryder Cup was played in Newport in 2010, the main attraction being Tiger Woods, the pub served several beers brewed especially for the occasion.

Where Commercial Street meets Commercial Road at George Street, the Alma, having graced the corner since Victorian days, retains the name and a pub sign but has been converted to a corner shop. From the Battle of Alma in the Crimean War in 1854 to the Napoleonic Wars, just a few yards away across George Street, stands the pub named after the highest ranking officer in the British army to be killed at the battle of Waterloo, General Thomas Picton. Considering he was active in the slave trade and known for his cruelty as governor of Trinidad, I am surprised that the pub sign bearing his portrait still hangs in these days of protest and the removal of such figures.

The Alma and Picton Arms are relatively recent closures, contributing further to the staggeringly large numbers of pubs that have closed along Commercial Road and adjacent streets since the publication of The Pubs of Newport in 1997. Most of the buildings still stand, converted to other uses or derelict awaiting fate: the Castle Hotel; the Welcome Home Inn; the Commercial Inn; the Windsor Castle Hotel; the Falcon Inn; the Mariners Hotel; the Alexandra Inn; the Cambrian Inn; the Kings Arms; the Top of the Range Club (formerly Olive Branch Inn); the Royal Exchange, the Irish Club. In side streets near Commercial Road you would have also found The Dolphin; the White Hart; The Cumberland House; The Tredegar Arms and The West of England.

The most remarkable of all Newport’s pubs is or was the Waterloo Hotel with its imposing clock tower, ornate interior tile work (similar to the Golden Cross in Cardiff) and luxurious interior oak-panelling. A unique frosted glass window lettered Workmens Dining Room indicates that the premises were divided into areas for the working and up-market mercantile classes. In the same vein, The Mountstuart Hotel at the dock gates in Cardiff had its ‘Captains Room’ separate from the public bar. The Waterloo must have offered luxurious surroundings and accommodation to ships captains, owners, agents, colliery proprietors, and business owners connected to the port. Local people too, though they had plenty of choice in the back streets of their neighbourhoods.

Of the numerous pubs that once stood in Pill, only three are still trading: the Ship and Pilot; The Church House (in local lore the birthplace of W.H.Davies); and at no.2 Jeddo St, The Royal Oak.

If ever my connections with a community pub, despite the drastic decline in numbers, had unexpected benefits, it was in Pill, in the Royal Oak in Jeddo Street. I’d never been in after photographing the exterior in 1995 for The Pubs of Newport.

Curious to see what it was like, I walked in one Saturday in early 2017. The place was busy, with lively conversation – raucous at times – without the usual pool table, fruit machine or music dominating the ambience. The lounge was a gathering place for even the occasional family stopping in to get their kids a bottle of pop. But the unusual feature in both the lounge and public bar were paintings by local artist and ex-merchant seaman Bill Coughlan. I asked the landlady Helyn if he frequented the pub and was told that he came in for a pint on a Sunday lunchtime. I mentioned that I was interested in his paintings and would like to chat to him.

The next day, a Sunday, he came in and we had a significant chat during which I mentioned that I was exhibition organiser for Cwtsh Community and Arts Centre and would like to show his work in the gallery. He was reluctant at first but eventually agreed, provided I could find enough of his work which he’d never shown before, except in Pill pubs – the Cambrian, West of England and the Royal Oak. He was in the habit of giving his work away. Paintings were in the houses of friends and family, in Pill, in Cwmbran, other pubs, in fact in other parts of the world where he had painted while at sea ex-merchant seamen friends.

It took several months to contact the owners and get a collection together, but finally, in October 2017, the exhibition ‘All at Sea’ was launched at the Cwtsh. Very sadly, Bill, who had been terminally ill with cancer and refused medical treatment, died four days before the launch.

I’d sent him photographs of the paintings and the gallery, hoping that he would survive long enough to see them, but it was not to be. Needless to say, the gallery was full of his family and friends for the posthumous opening. Bill Coughlan was also known in the community for designing and painting the Royal Oak pub float for Pill Carnival on August Bank Holiday. After he died in 2017 his work was carried on by his niece and I was able to photograph the Disney-themed artwork for the float, the makeup session in the pub on the day of the carnival and the float as it prepared to leave the docks as it joined the carnival procession in Commercial Road.

In the early days of the twentieth century Newport’s three breweries had almost 140 pubs, tied houses, with most of them surviving until the 1960s. Today just 25 that survive, not as tied houses but owned by pub groups, some large such as JD Wetherspoon (Tubby Linton, Tom Toya Lewis, Godfrey Morgan, Queens), some small, such as JW Bassett (Carpenters Arms, Pen and Wig). The building of new housing estates since the end of the second world war and expansion in more modern times, has included either the building of new pubs, especially in the 1960s, or conversion of nearby older buildings.

Since the 1990s several pubs and breweries have opened and some closed. 2012 saw the opening of Newport’s first microbrewery, Tiny Rebel, which has has become so successful that a new, purpose-built brewery and pub in Rogerstone started brewing in 2017, becoming Wales’ biggest. Their first pub opened in Cardiff in 2013 before the Urban Tap arrived next to Newport Market in 2015 where it traded until March 2024. Two micro-pubs located in former shop premises have opened since 2017: the Cellar Door in Clytha Park Road (2017) and the Weird Dad ‘bar and nano brewery’ (2021) in Caerleon Road, opposite the Cenotaph in Clarence Place. In between times, the Little Tap House in Baneswell Road opened in November 2023 but lasted less than a year.

Wetherspoons in particular has ‘saved’ some older iconic buildings and named them after historic figures. Maindee Cinema has become the Godfrey Morgan, the YMCA has become the Tom Toya Lewis, and in Cambrian Road, the first Wethersppons in Wales, named after Newport-born naval hero John Wallace ‘Tubby’ Linton. Many former pub buildings in Newport survive as shops, offices, takeaways, Indian restaurants, even housing for the homeless. The Murenger and LePub host regular poetry reading events. Other twenty-first century pubs, on the outskirts of Newport include the Dragonfly, at Celtic Springs, Coedkernew, the Llanwern Bull at Glan Llyn, on the former Llanwern Steelworks site and the Blaina Wharf at the site of Old Town Dock.

And so it goes. Recently I had an exhibition at Cwtsh entitled Down Your Local? – images of pubs from the 1990s to the present. I was compelled to use a question mark in the title, for as the photographs demonstrate, if you live or have lived in Newport and had a local pub, it may or may not still be there.

But who knows? You may well find another establishment has taken its place or may not be far away. You may well be influenced to move out of your local community to find an establishment that suits you, for the choice of food, entertainment and drink has never been so varied in the city and its suburbs. This is despite the hospitality sector being hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic, and now the new Labour government being criticised for its small business unfriendly policies, especially the increase in National Insurance levies, increase in the minimum age to employees, raising business costs which pub owners say they cannot afford and will cause further closures.

But even if it can’t be in what you once knew as your local, where the once-familiar call for ‘last orders’ followed ten minutes later by ‘time please’ may not be heard as you sup your pint until midnight, it’s still time I say ‘Cheers’ to all.

John Briggs was born in 1947 in St Paul, Minnesota. He came to Wales in the 1960s to study at Atlantic College in the Vale of Glamorgan, where an increasing passion for photography resulted in his first street images of Cardiff. He gained a degree in French at the University of Minnesota, also working as a part-time reporter. Returning to Wales to do teacher training at University College, Cardiff, he began systematically photographing the city’s disappearing docklands. His books include Before the Deluge, Taken in Time and Newportrait. He has also published Walking Cardiff and Walking the Valleys in collaboration with Peter Finch.