'A Site of No Interest': Notes from Hillside, Hillside

As the National Eisteddfod arrives in Pontypridd, Richard Huw Morgan takes a ramble through the area's farm lanes and deep histories – and contemporary concerns about the area's future

It’s not an easy walk up the lane on the south west slope of Cefn Eglwysilan for my sixty-year-old knees. Or should that be Mynydd Eglwysilan? Ask the nearby Garth. Higher ground in this part of South Wales seems to have an identity crisis… or possibly a habit of shape shifting. Or is it simply different ways of seeing? One person’s hill is another’s mountain.

I digress, and – to warn you in advance – this will happen again. I am writing this in the here and now; it is both the first and the final draft. The maquette and the sculpture, the script and performance. By the time you read this some bits will have fallen off, others fallen in.

Thirty-five years of an unintended career in experimental performance with neither the necessary training nor the knee pads have played havoc with my joints. I try to do the recommended exercises, tell my physio that I have. In reality I have a low boredom threshold and there is nothing more boring than ‘exercise’.

Walking, on the other hand, is a different matter. After a brief pause and swig of fizzy water I grit my teeth I’m off again. It’s worth it. This year’s rare summer sun cusps with cloud, revealing the occasional floodlit field straight out of RS Thomas’ poetry.

At the end of the lane lies the farm that lends the place its name: Bryntail, or in other times and on other maps Bryn Tail or Bryn-tyle. So you can take your choice: ‘the Dung Hillside’, or perhaps the ‘Hillside Hillside’, or some such. The farm buildings are nothing special to look at, nothing to distinguish them from the many farms in the area built next to a spring.

Bryntail possibly began as a Hafod, the summer farmhouse when the sheep were set to roam the higher pasture as opposed to the Hendre for overwintering. Hendre Prosser that I passed on the way up with its tasteful renovation and yellow swatches painted on the rear wall looked a far more likely candidate for ending its life in St Fagan’s. Then again, that is no longer a working farm.

Bryntail is a working farm, and unless you are visiting, you have to walk to reach it. There is nowhere to park here. The buildings have been remodelled to suit both working needs and style and fashion modifications deemed suitable by the generations of inhabitants.

According to my internet research the primary business here is sheep, with a small herd of milking cows, on 580 acres of hill/upland farming land. That was before the pandemic. I’ve not seen the cows for a while but the sheep remain lazily grazing the hillside. But that is set to change next year. I’ll get back to that later.

To understand the importance of this place you need to look elsewhere, to turn away from the modified farm buildings and to refocus on the more enduring structures. The drystone walls that surround the fields.

Practical yes, but also exquisite in places. The work of craftsmen. Repaired and rebuilt over generations yet retaining the hallmarks of one of the most remarkable residents of the farm, who makes this place so special and important in the history of the region. William Edwards.

A Methodist minister by vocation from his early twenties until his death aged 70, Williams had a sideline in stonemasonry. At just 27, and with no previous bridge-building experience, but with plenty of evidence of his craftsmanship surrounding Bryntail, he was commissioned to build a new bridge over the Afon Tâf at the site of, or near, the old Pont Y Tŷ Pridd.

After ten years and three failed attempts, in 1756 a bridge finally stayed up, and remains up to this day. And the site of the new bridge – built in open countryside as shown in contemporary paintings, including one in the Tate by JMW Turner – began to develop and became the village Newbridge.

For half a century Newbridge would slowly develop at the junction of the Taff and the Rhondda rivers, a small market town serving the surrounding scattered farms and hamlets.

In 1792 the construction of the Glamorganshire Canal reached Newbridge ploughing it’s way from Merthyr Tudful to Cardiff, and things started to change more rapidly. By 1856 there were so many people in the town – probably complaining about missing post getting sent to Newbridge in Monmouthshire – that the local postmaster Charles Basset petitioned that its name be changed to Pontypridd. It stuc, testament to the power of the postal service in previous times (Pontypridd’s old main post office is now a Wetherspoons).

A week ago I wrote this:

I’m writing this as I wander, in entirely the opposite direction from the site that I started writing about, feeling slightly guilty that I’m not paying full attention to the road that I’m wandering. But then again, ‘the powers that be’ have done their best to obliterate most of the marks of interest and those that remain I’ve read a thousand times before. I pass the old tunnel that led cattle from what is frequently claimed to have been the world’s longest station platform to the site of their slaughter. From Parc Ynysangharad you can see the remains of the slaughterhouse and imagine the blood and entrails sluicing through the bricked up orifices into the Taff. On that site now stands the ‘Job Centre Plus’. Deep maps.

This was the same road I was walking in early March 2020, my brain fizzing with excitement at the possibilities of starting R&D on our forthcoming Wales Millennium Centre commission: a large scale, multi art-form, multi-site, multi-lingual week-long festival for Pontypridd when the Eisteddfod visited Rhondda Cynon Tâf, because obviously the Maes would be elsewhere right? No-one in their right mind would combine the ever-so-regular traffic chaos of Pontypridd with the ever-so-regular traffic chaos of the Eisteddfod, surely?

It was one of those misty, foggy, mornings when the particulate pollution stays low to the ground, about head high, when a thought struck me. How much time and energy is spent, wasted, in the moving of people from one place to another, from residence to workplace? What if we all stayed at home for a few months? It was just supposed to be a thought experiment, not magical thinking…

Yet this is all relevant. This route is the old dram road, built by Richard Griffiths in 1809, that brought the first coal from the Rhondda – a five mile stretch from Hafod Uchaf to Trefforest, which predates development at Newbridge, and then a further one mile canal linking to the main Glamorganshire Canal.

Griffiths – possibly Dr Griffiths, possibly not – was born the year of the completion of William Edwards’ successful bridge. Whilst Griffiths did not build his own bridge he did have one named (or at least sometimes named) after him: Pont y Doctor. Sometimes also known as the Machine Bridge. Because of course, why have one name when you can have two?

By 1839, 200,000 tons of coal were being carried over the Machine Bridge. Like Edwards’ ‘new’ bridge it is still there. You can see it if you know where to look: under what looks like an electricity pylon crashed onto its side. This brace is holding what is believed to be the earliest surviving multi-arched railway bridge in the world from falling into the Tâf. It was along this road, on which I live and am now writing, that the black gold that spewed out of the Rhondda spread and maintained a global empire. A sobering thought.

Back to the walk of a week ago.

Near the Wetherspoons, the Broadway is six vehicles wide: four lanes of traffic and two ‘controversial’ new bus stops. Nothing is moving. People are fuming. I have no idea what they are thinking, or in which language they are thinking it, but if the lively local social media sites are any indication there will be a large number of the fuming people blaming the Eisteddfod, at the time of walking and writing still two weeks into the future.

We have reached a point when everything that is happening in Pontypridd is ‘controversial’ and there is nothing that cannot be shoehorned one way or another into blaming the Eisteddfod. My favourite is the increase of the local rat population. Apparently this is due to the forthcoming celebration of Welsh language culture.

Once the Eisteddfod has been and gone and the chaos remains, fume will be refocused, probably directed to the local council and renewed demands for progress in ‘sorting the problems out’. Quite probably the demands will come from the same people that blame ‘the council’ for destroying the built heritage of Pontypridd by trying to sort the problems out.

So, how does all this link up?

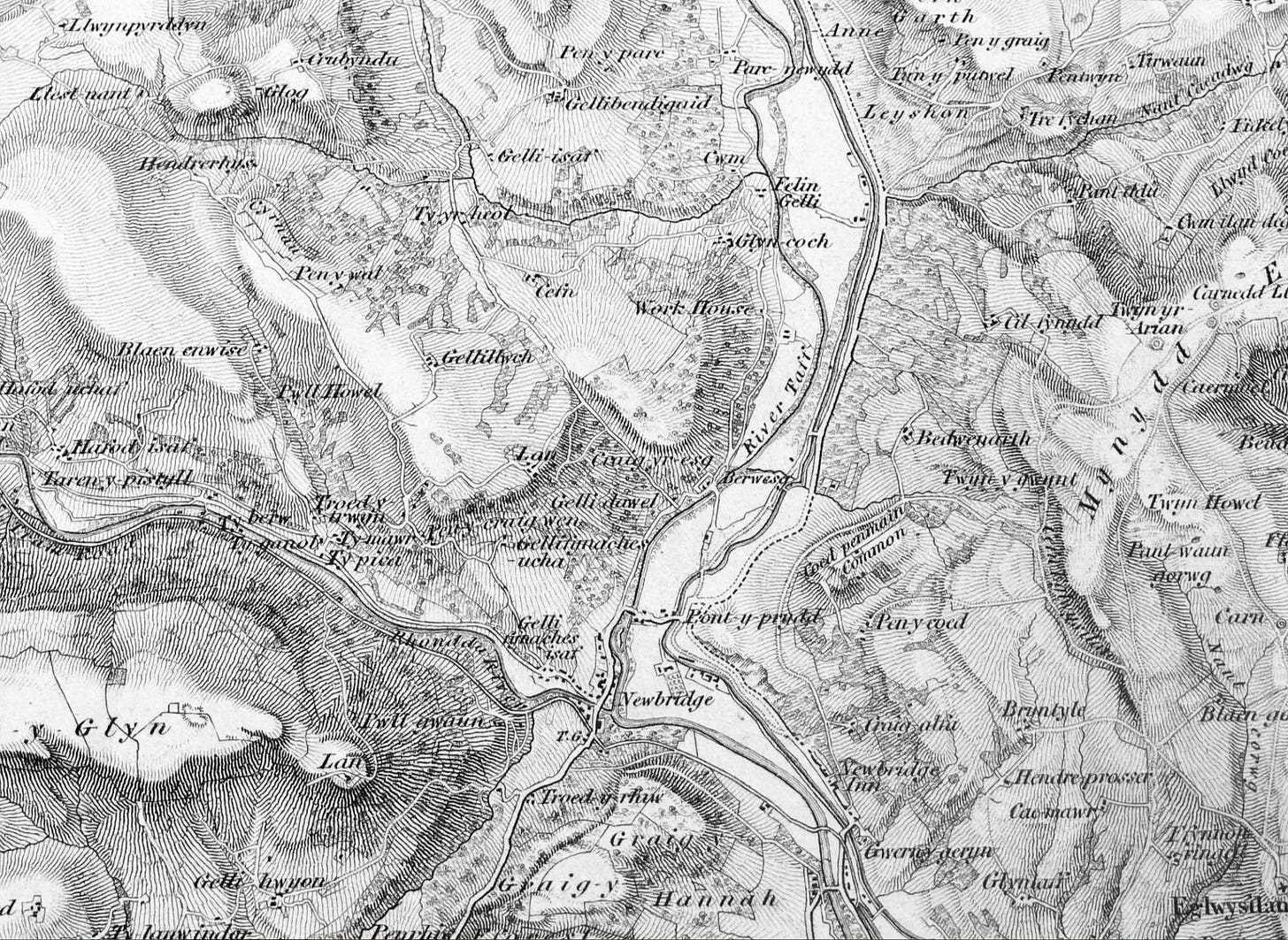

As old maps show, what was once rural south east Wales – with scattered farms and hamlets at fairly evenly distributed distances and altitudes – was completely transformed by the industrial revolution into ‘The Valleys’. People moved from all over Wales, Britain and further afield in their droves and pretty much stayed. Attention was focused away from upland habitation and religious sites, such as medieval Llantrisant, Llanwonno and the pilgrimage site at Penrhys, and into the valley bottoms – to transport mineral wealth down to the developing ports on the coast.

To digress again, it has been suggested that the pilgrimage to Penrhys might have been the reason for the construction of the New Bridge / Old Bridge, though with Edwards being a Methodist minister first and a stonemason second it seems highly fanciful that he would spend ten years of his time facilitating such idolatry. The more likely reason for its construction was for movement of animals, though it proved pretty useless in general and particularly for those drawing carts.

As ‘The Valleys’ replaced Y Fro, Y Cenefin, Y Filltir Sgwâr it was mainly coal and goods that moved across, through and out of the region, not the people. Everything social was provided or developed on a local basis. Work, Church, chapel, another chapel, pub, club, another pub, cinema, institute, shops – all within walking distance. Those people that did move were secondary users of infrastructure designed for industrial purposes.

Fast forward through time, industrial growth and decline, and walk back up to Bryntail, through a lane that to date remains unchanged by that process. But perhaps not for much longer. Bryntail Lane is the main proposed access route for the development of the Glyn Taf Solar Farm. It is currently the width of a small car.

In June 2024, I attended a public consultation organised by the proposed developers Renantis, who have since rebranded as Nadara. Neither name seems to mean anything, certainly not in Cymraeg – though interestingly when I entered ‘Renantis’ into Google Translate from Cymraeg to English it guessed at ‘Tenant’. Nadara drew a blank, though it did suggest in the language of the Somali communities of Wales that it means ‘rare’. I digress.

Whatever they are called this week, or by the time they get the permissions they are seeking, the company are an international commercial developer which has by some means or other been handed the rights to develop the site, and unless the Welsh Government decides otherwise, despite whatever objections are raised, construction will begin in 2025.

Perhaps they will do what another beneficiary of the Welsh Government’s opaque energy policy has done: change their head office location and rebrand themselves as somehow Welsh without quite understanding the wider implications of the name they have chosen. As the would-be wind farmers have taken ‘Bute’ perhaps the sun-soakers could choose ‘Longshanks’, just to remind us of our status as England’s first colony. (As I typed this the first time ‘Pages’ on my iPad unexpectedly quit and that final line disappeared. I am not paranoid).

I am a strong supporter of the generation of energy from non-fossil and non-nuclear sources and have been for an extremely long time. When I was working for Cyfeillion y Ddaear / Friends of the Earth Cymru back last century I imagined the daffodil shaped wind turbine long before the first, then second, bloomed near Llantrisant.

Back then the environmental priority for future power generation issues was firstly to reduce usage. Only later has the priority shifted to building more capacity as necessary for consumption. Reducing consumption seems to have fallen off the table in the Capitalisation of the ‘Green Agenda’.

Energy generation is now championed as the deliverer of the ‘new clean/green jobs of the future’, of profit generation and a satisfier of our wants rather than our needs. Wales is a net exporter of energy, admittedly not all of it generated from renewables, but if we are serious about our future needs then I would really like a demonstration of some joined up thinking that relates production to the needs and benefits of the people of Wales.

What I do not want to see is a supposedly democratic government granting piecemeal rights to outside financial interests to once again utilise the natural resources of Cymru for their own private profits with the supposed benefits to local communities being what seem like arbitrary ‘gifts’ of beneficence to whosoever they deem ‘worthy’.

And here it all gets very complicated, and mapping of the surface landscape will not suffice. We need to talk about land ownership and land management, and about farm diversification in the wake of Brexit. Bryntail farm borders Eglwysilan common. I’m not suggesting that a solar farm should be placed on common land, but if it were, would the very lucrative rent paid to the farmer on top of his continued business be paid to the local community? Probably not.

At the Renantis/Nadara ‘consultation’ a very nice young chap pointed out that this development was for the benefit for the people of Cardiff. I pointed out that we were not in Cardiff. He suggested that the electricity generated would be needed for us to all transition to electric cars. I suggested that electric cars might not be the solution for an area that developed, for better or worse, on the presumption of not moving.

This has become a mighty long preamble, or ramble, around or about what I came here to write, but perhaps that is the point. All this is about what you choose to focus on and on what others would prefer you to focus. The power of narrative.

So to the crux of the matter. Why I’ve climbed up here today.

At the Renantis/Nadara ‘consultation’ there were a series of information boards setting out the aims, intentions, motivations, social responsibility etc of the company. Basically their website turned into a series of large prints. None of the information was new, but seeing it all at scale and side by side something struck me.

Among the promises of potential community benefits for local clubs and societies, along with the promises of increased biodiversity – somehow as the result of the farmer not doing something he was not doing already – there was this on the strangely titled ‘Archaeology’ panel: ‘There are no designated heritage assets located inside the proposed development’. ‘There are two internal non-designated heritage assets; the remains of a former sheep wash and the (mislocated) record for the nearby village of Rhydyfelin’. I have no idea what that last bit means.

While the accompanying map identifies the architectural wonder of the New Bridge / Old Bridge with the simple word ‘Bridge’, there is no linking of this to the former inhabitant of Bryn Tail. Nor of William Edwards and his walls, the role he and his building skills played in the development of Newbridge / Pontypridd, and the global impact of that development.

For the outside eye there was nothing to see here. It is the same unseeing outside eye that declared in previous episodes of colonisation that Epynt and Tryweryn were empty landscapes. No understanding of history, nor of community. Simply an opportunity for development – for the benefit of other people in other places.

The outside eye fails to understand the Deep Map, the meaning or rather contested meanings of things. Yes, the boundary walls of Bryntail farm fields are shown on maps. As a simple black line – not in their magnificence, nor their significance in the development of this part of the world.

And why do these walls exist? To separate private property, and private income generation from renewable resources, from ‘common land’.

These are live questions in the week that the Crown Estate announced record income. A Crown Estate set to earn millions more from the exploitation of ‘the King’s Seabed’ around the coast of Wales for the development of off-shore wind power. A Crown Estate devolved in Scotland providing vital revenue to the Scottish Parliament but denied to the people of Wales and our parliament to help solve our very real, and geographically particular, problems. Truly England’s first colony.

We are the product of time and space. History and geography. Or rather histories and geographies. These are not neutral, objective, terms but constructs used to direct narrative. I am walking this path through this town in this post-industrial region because of the work of one of the inhabitants of Bryntail.

Oh, and by the way, Dr William Price also lived at Bryntail for a period of time. But his life and influence on contemporary society are an entirely other story.

Richard Huw Morgan is an artist, performer and presenter based in Trefforest. All photographs are by the author; the map is in the public domain.