A raging, turbulent, furious place: notes from Severnside

Merlin Gable revisits the River Severn, the site of bridges, tunnels, photographs, and a great wave

It’s the brief strum that announces it, and then that unexplainable floating feeling as the ground sinks away beneath you. Gun the throttle a bit and it’ll feel like the moment the aeroplane takes off. Beneath you, you’re never sure which you’ll get, the swirling taupe of the mud bed or the off-blue estuary. Above you, the rugby post columns frame the sun like a henge.

When I was younger, waking up to see the foam green barriers and the prowing stays meant the final stretch of a journey – a quick about turn at Newport then dual carriageway giving way to single carriageway giving way to lanes before home. Then, we all agreed that the green was an awful choice, ‘Severn Bridge green’ a shorthand for the most unattractive shade between green and turquoise. Maybe it’s the colour of the sun today but now I’m not so sure – I guess time does that.

When viewed together, the new bridge is so much more pedestrian than the old: a cautious staking of pillars into the mud, a gnashing green mouth of a bridge compared to the soaring elegance of the white one which still feels the more modern, stepping lightly off the architect’s drawing onto Beachley, before leaping over in one go. That one is a true suspension bridge, but then again the modern one has its rugby posts and a ‘harp design’ stay arrangement – a coincidental nod to cultural vernacular.

Up comes Paul Simon’s ‘Graceland’ on my Spotify queue, that ducking bassline and clapping drumbeat readying me for the swoop and sweep of the river and the bridges.

The Mississippi delta

is shining like a national guitar.

I am following the river down the highway

to the cradle of the Civil War.

Our civil war is too far gone – although the images of police blockades on the Severn bridges during Covid lockdowns was enough to quicken the pulse of some – but I’m looking for something.

I’ve always been struck by the simplicity and blind boldness of that first couplet. For a nation of song, we’re never so confident nor so clear. I’ve just come back from America, where the roads unfold like stories and stories seem as straight and wide as the highways. We’ve no such easy idiom to describe places like I’ve come to today – in general we’ve not achieved their easy mythology of the modern world. We’re at home amongst the trees and the rocks, we’re even getting there in the panoramas of post-industry, but our backwaters and byways are resistant to eulogy. But if it can happen anywhere, I think, it can happen here, cruising over the mudflats of the Severn – our own Mississippi. In a peculiar way, I’ve got a feeling that this is where it happened – this is where it all started, at the end of things, at the end of the Severn and the end of Wales.

The Severn is steeped in stories; it is charged with meaning. When the new bridge was renamed to the ‘Prince of Wales Bridge’, the petition to stop the renaming reached 38,000 signatures. Despite it now being the big-ticket entry point to Wales, this method of making the crossing is relatively modern as the default choice. It was borderline impractical before 1966 and downright dangerous enough in 1727 that Daniel Defoe chose to divert all the way up to Gloucester (inexplicably via Chipping Sodbury) rather than chance the ferry:

When we came to Aust, the hither side of the Passage, the sea was so broad, […] the tide so formidable, the wind also made the water so rough, and which was worse, the boats to carry over both man and horse appear’d […] so very mean, that in short none of us car’d to venture: So we came back, and resolv’d to keep on the road to Gloucester.

It all feels like a bit of a tangle to be straightened out. We know some of the facts: there’s two bridges, the old one and the new one whose name we don’t like, and there’s a railway tunnel replete with pub quiz facts about how much water enters it and how often the rails need replacing. There’s a famous photograph of a ferry crossing, and there’s another much less famous ferry crossing and there’s a final railway bridge.

And then there’s the bore. I think often of the Severn bore – it occupies my dreams. A rare tidal phenomenon, it is caused by waves starting out in the wide Atlantic, moving at 700 miles per hour. When they get closer to Europe, their speed is reduced by the continental shelf, correspondingly increasing their height. Taller and narrower, slower and higher, the bore enters the Severn from the sea as a fifty-foot-tall swell. This is what Defoe was so frightened of: ‘those violent tides call’d the Bore, which flow here sometimes six or seven foot at once, rolling forward like a mighty wave: So that the stern of a vessel shall on a sudden be lifted up six or seven foot upon the water, when the head of it is fast a ground.’ Biblically, the waters reverse themselves and the tidal wave rides up the Severn towards Gloucester. A front, hundred of miles wide, is refined to a pulse strumming down a line along the river that divides England from Wales.

Except of course, it isn’t ever really the border in any clean sense. The Severn captures the contradictions of the place: the totemic river of our border, born in Pumlumon in Powys, spends most of its time in England and only actually forms the border for about one kilometre near Welshpool and these desolate banks in Gwent. From Chepstow you can cross the Wye northwards or the Severn eastwards to find England.

But none of this is making it any clearer. This place is older than all that – the Kingdom of Gwent held court in Portskewett; the Romans were here. Its patterns are made by the river but they move like the tide – ebb and flow, washing away the old too quickly to make something of it. It’s older than Wales but it’s perhaps one of our most famous locations now. I went to Severnside looking for something but I’m not sure what. Maybe in our foyer, our last chance saloon, I’d find something that made sense finally ‘of Wales’.

The roots are certainly ancient here, even if they struggle to hold onto the banks. My first stop off the motorway is Portskewett, found down a tangle of B roads, first through Magor-of-service-station-fame, then Caldicot, all older than but fundamentally arranged beneath the two vast roads that carve along either side – the M4 and the M48. Caldicot high street is quiet like a Western at 10am on a Saturday. In fairness, it’s raining a bit by now, fine and urgently, but within ten minutes it’s ragged sun again and the silence remains.

Portskewett church is yellower and browner than you’d imagine. Cadw insisted, a man opening up the little museum in the churchyard tells me, that they limewash it a traditional colour when it was renovated. But the difference between now and when the church was built, when everything was limewashed yearly, is that nobody can afford the time now for limewashing, and nobody will stump up the money either. I struggle to see the church as it would have been, surrounded as it is now by modern housing and in its strange, bedraggled carnival colour.

The museum itself is in a hovel – no more than four metres by two – that used to exist outside the churchyard before it encroached in need of space. It is well restored and holds a wealth of information on the area. A walking group are imminent and will expect teas, coffees and squash when they arrive. They’re walking between three churches today, the man explains, and ending with a lunch. I struggle to explain my own journey in response: I’m here because I’ve been here too many times before without wondering what was underneath the bridge, I say. And also because I know the bridges weren’t always here, so I want to understand what came before. ‘You’ll need to head down to Sudbrook I’d have thought then,’ he says after some reflection. So I step back out into the blustering, weak sun.

Sudbrook is a village with a purpose. Two long streets stretch down towards the estuary either side of a railway line now closed but still bisecting the village with an unkempt eco-garden of buddleia and bramble. At the end loom the pumping towers – big Victorian buildings that are as essential today as they ever were. The Severn tunnel, you see, cuts straight through a spring and would flood rapidly if it weren’t for the constant efforts of the pumping towers. Another spring, the one that brought the Gwent rulers down, closed up when the tunnel was dug, as one moment of history gave way to another, as two nations were girded together for the first time by transport. The Bristol economic area, anyone?

The best view of the pumping towers I found was from the Roman camp, whose name is self-explanatory enough, and next to which sits the ruins of a medieval church, three different eras stacked next to each other like books on a shelf. From closer by on the street, its harder to see them as more than just looming buildings, fences, gates and warning signs – some relevant, some still under the impression the railway runs through here.

Sudbrook is a frontier village, formed on the cutting edge of innovation. It housed the workers who built the Severn railway tunnel, some of whom lived in some of the first concrete houses in Britain. Shipbuilding and a paper mill later occupied its residents, three muscular industries that presumably gave rise to the sports and social club, now in part the Tunnel Centre, devoted to the history of the building of the tunnel. Technicolour Thomas the Tank Engine murals crowd out the dim corridor of the Centre and the exhibition room is locked. I head back out into the drizzle and cock my camera shutter – quickdraw.

By the time I walk over, the drizzle has moved on and clouds are sculling across the New Passage. They’re the last ferrymen here, carrying rain showers like messages between the two banks. Previously, another railway veered off before Sudbrook and ran to the pier at Blackrock, where you’d disembark for a ferry and be met by another train on the other side. The hotel on the English side, designed for knees ups when the river was too rough for the crossing, became a fashionable spot of its own to visit on day trips from Bristol.

All this came to a sudden end when the Severn tunnel opened in 1886, allowing trains to move directly between England and Wales across Severn for the first time. Suddenly Cardiff, Newport and Barry make so much more sense when you realise that the easy passage of freight into England from south Wales only began in the final fifteen years of the nineteenth century. By 1891, Cardiff was 129,000 people and exported millions of tonnes of coal a year. Yet five years earlier you had to wait for a ferry between trains to get to England.

On the Welsh side, it seems the tracks were dismantled and the smaller inn converted to housing. Now a picnic area fills the site in the shadow of the new bridge, bisected by the desire paths of years of children’s chases. There’s the shed of a fishing club whose ancient handheld-net-based method of salmon fishing is barely any longer allowed by Natural Resources Wales, so they’ve closed up shop in protest. A man is instead fishing for crab at the old pier whilst his daughter stomps across the rocks. Above them, bisecting sky, rock and sand at Bauhaus angle is the new bridge thrumming up to its morning capacity. The father has come up for the day from Bristol. I don’t ask him which bridge he crossed, or if he’s thinking about the ferry which he could have stepped onto 150 years ago. Instead, I’m thinking about my own father, and a site of pilgrimage of sorts that we went to sixteen years ago just over the water.

Before too long and one border crossing later (old bridge), I stand in the waving rushes at the Aust ferry terminal, barely peeking out of their summer growth to see our old friend, the white bridge, off in the distance. The slipway wasn’t as overgrown when I was here with my dad aged thirteen, and the refreshments hut and ticket office, complete with turnstile and urinal, still just about stood beneath brambles. Now, that’s all gone, swept away by a tidal defence system that has replaced the gentle slope to the river with a hard wall, protecting the houses above. Pushing through the rushes, I’m wrong-footed as the slipway deck suddenly runs out – only the pillars left heading out towards the water. I’m alone and suddenly feel vulnerable to the quicksand and the tide. I nervously check my phone for when the high tide is coming. The rushes whisper and chatter around me as I look beyond them at the bridge that spelled the end of this ferry crossing.

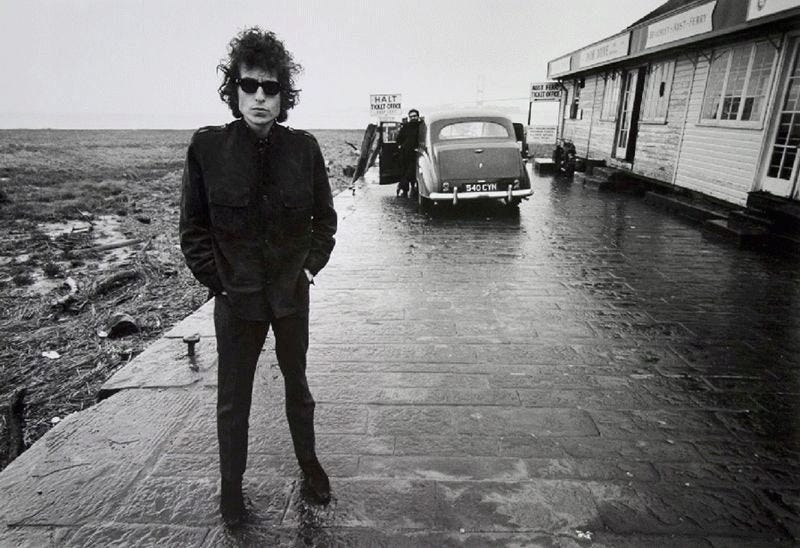

In its final days, in May 1966, a cool 25-year-old Bob Dylan stood on the same jetty waiting for the ferry crossing. Barry Feinstein took the opportunity to take a picture of him. He was on his way from Bristol to Cardiff as part of his infamous first electric tour; he looks pretty tired of it all. Behind him, like a pale ghost retreating, is the Severn Bridge, waiting to take over just four months later. The last ferry to cross the Severn was the day before it opened.

Just upstream from Dylan’s photoshoot – out of sight, definitely out of mind – was the Severn Railway Bridge, struck (not for the first time) by boats carrying petrol in 1960 with predictable result. The rushing tide pulled them upstream of the entrance to Sharpness Docks and, shrouded in fog, they collided together and then collided with the bridge. That bridge, an awkward 90 degree turn on both sides of it, connected the railway line at Lydney on the ‘Welsh’ side (still in England) to Sharpness and its canal to Gloucester on the English side. In 1966 it was still mostly complete, but its fate had been sealed by further collisions since 1960 and it was demolished in August 1967. Supporting that work was the Severn King, just relieved of its duties at the Aust Ferry a few months before. In 1969 it too crashed into the pier of the half-dismantled railway bridge and was scrapped. This must all mean something to local people, because the Severn Princess (rumoured to be the ferry in service for Dylan’s voyage) was saved from abandonment in Galway, Ireland to be towed back to Chepstow where it awaits restoration.

The famous photo later adorned the poster of the documentary No Direction Home about that tour. Standing at what was once the main route into south Wales for motor traffic, you can certainly feel it. At every place I go, the past seems to have just left, with only ghosts in its place.

Dylan also has a song about the Mississippi:

Well, the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay

You can always come back, but you can't come back all the way

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

There’s a very different version of our border here, of our relationship with England, but it’s hard to find – you can’t go back all the way. The pulsing, swelling, alive Severn is too unstable to hold any simple narratives of place, community, or border. Pulling together everything in its catchment – the ancient history of invasions, the more recent histories of transport and industry, the great bridges doing the work for the relationship between the two nations – the river is swollen with meaning it can’t sustain.

But all the same, life goes on around it across all the changes. I think enviously of the lower Seine in France, where small boats called ‘Bacs’ ply between towns on each bank, taking foot passengers and no more than ten cars at a time. They don’t operate on a timetable, they just ricochet for free between the banks, building a weave of interconnections across an otherwise insurmountable border. When the Severn Railway Bridge collapsed, the children of Sharpness lost their school in Lydney. The end of the Old and New Passages was the end of some small villages’ time in the spotlight: Defoe’s ‘little dirty village call’d Aust’ became barely worthy of a mark on a map. Dozens of small, never documented ferry routes further upstream disappeared without a trace and villages that once looked into each other’s eyes now sit distrustfully in opposing encampments. Sometimes the tide is so low that you could almost walk across; sometimes the Bore is rushing past, warning them never to try.

I still think of the bore. Perhaps it was a bore that took the entangled Arkendale H and Wastdale H upstream into the explosive embrace of the railway bridge – a modern day Nodens on his seahorse, riding up his river into battle with connectivity, with the joining of kingdoms. The Severn, the leaking wound of Pumlumon, rushing back upon itself like an omen, a river in reverse searching for its cot fellows, the Wye and Rheidol. Surely the centre will not hold; maybe there never was one at all, just the rushing tide up the river, coming bearing the flotsam of our jaded, ragged culture, sweeping away the certainties, washing away the mountains like sandcastles, leaving our beaches littered with the detritus of ourselves to be picked up and made again.

Or maybe it’s easier than all that – the toll is gone, the crossing is free, the journey is one made in a heartbeat. I stand at the end of my own journey, looking down at the wrecks of the boats at Purton ship graveyard. The tide is low and the foundations of the destroyed bridge can still be seen. Families explore and play amongst the ships’ remains as the weather finally cracks and rain comes down thick and hot. We all run for shelter but there’s none to find – the river has stripped the banks bare. Eventually, I get back to my car down at the yacht club, flushed and damp, and turn it back towards the bridge and towards Wales.

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long.

Merlin Gable is co-editor of Cwlwm.

There are so many adjectives one could utilize to describe this essay: brilliant, heartbreaking and courageous. I have only two words: thank you.